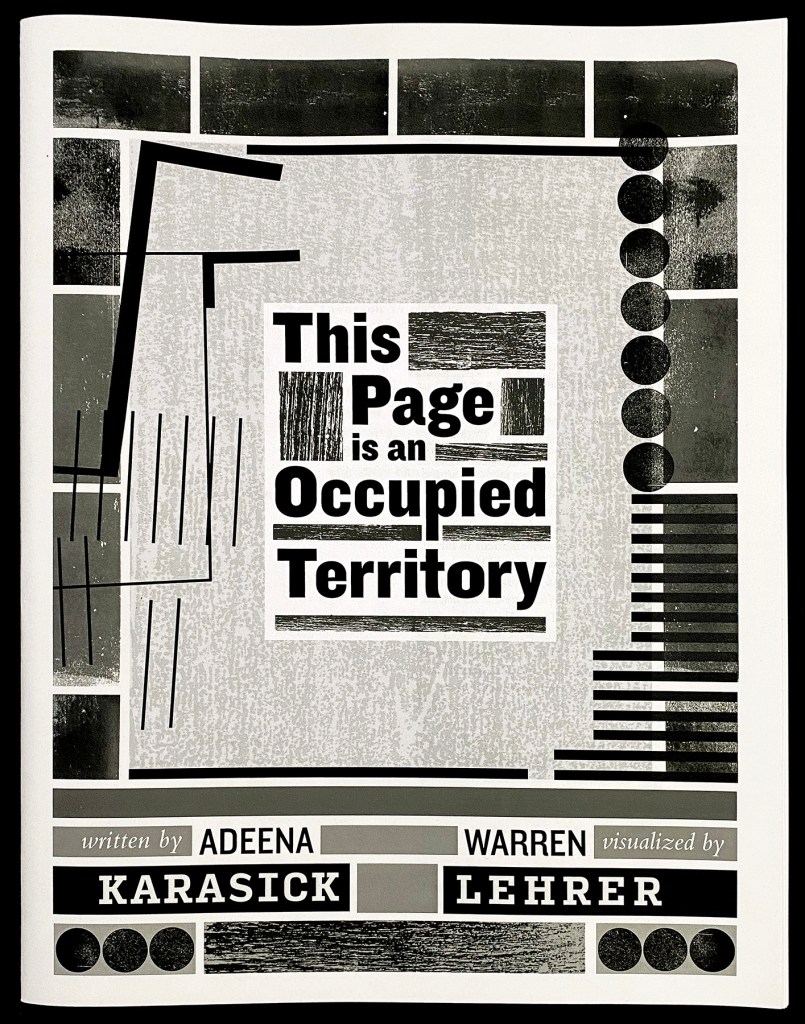

The Next Call was an experimental typographic publication designed, printed and distributed by H.K. Werkman, who started a clandestine anti-Nazi publishing house in 1941, and was executed by them only days before the occupation of The Netherlands ended. The Next Call was a major inspiration for Warren Lehrer’s most recent collaboration, This Page is an Occupied Territory, a typographic visualization of Adeena Karasick’s poem of the same name. Like other such experiments that came before it, it’s the perfect marriage of method and meaning—and printing/design as medium and message.

Lehrer, co-proprietor of EarSay, has taken a long road of typographer as author and authorial enabler. Moreover, his work is often made for the stage, so the static page is not simply an object but a performative experience.

Lehrer and his wife/EarSay partner, Judith Sloan, are doing a performance/reading from selected books and theater works of theirs at 2:30 p.m. on December 8 at Art New York (520 8th Ave.) in Manhattan. Sloan will be joined by Palestinian American actor and comedian Grace Canahuati. Books will also be available for sale, including This Page is an Occupied Territory. For more info and tickets, click here. And regardless of whether or not you attend, read the Q&A below.

Warren, you’ve been on a publishing fast-track these past years since COVID. What has triggered this continuous vigor in making text and ideas come alive through typography?

About six years ago it dawned on me that I didn’t have to only work on seven- or eight-year long projects that I write (or co-write) and design myself. I started collaborating with poets whose work I adore and who trust my sensibility, visualizing their texts into books and animations. I also stumbled into the realization that not every book had to be 300 or 400 pages (duh!), and I could work on shorter projects while continuing to work on longform ones. Yes, COVID probably had something to do with finding more hours in the day. I lost some dear friends and relatives to COVID, which was heartbreaking. But frankly, like many writers and artists, the pandemic was a hugely productive time to submerge into studioland. Also, in 2020 I liberated myself (I don’t use the “R” word) from being a full-time professor. I still teach one class (at the SVA Designer as Entrepreneur MFA program that you started, Steve), but that’s a whole different amount of time and psyche commitment.

So, yeah, I’ve come out with four publications within a little more than a year. Three of them are timely works. One related to coming out of a worldwide pandemic, and two of them speak to the war/slaughters going on in the Middle East. Publishing can be awfully slow, and I very much like this process of creating works born out of a particular cultural or personal moment in time and getting them out there soon after they’re finished.

Lastly, I’d say, these newest publications are more spare, in almost every respect, than many older works of mine. I’ve been a maximalist for a long time, creating dense works—an illuminated novel with 101 books within it, a four-book portrait series of over 1,000 pages, a documentary project chronicling 79 new immigrants and refugees from all over the world that juxtaposes multiple perspectives often on a single page. And typographically, I have a reputation for using dozens of typefaces in a project, as I’ve attempted to portray character and voice through typographic casting, composition and expression. Two of the four new publications are based on short stories of mine where the writing is more pruned, and two are poetry, which almost by definition is a matter of distilling language. I only use one weight of one typeface for the text in this new piece, which is very new for me. And with all the recent poetry collaborations, the typographic compositions are less about voice and more about diagramming ideas, finding hidden meanings and visual metaphors that emerge from the texts and the very human experiences they represent.

Adeena Karasick at the podium.

Your most recent publishing “event” (I use this word because it is print, poetry, performance, typography and more) is This Page is an Occupied Territory, written by Adeena Karasick and “visualized” by you. Before we discuss what it means to be a “visualizer,” tell me what about the intention of this tabloid newspaper/magazine-style publication?

Adeena sent me several new poems with the idea of us doing another book together. (We came out with Ouvert Oeuvre: Openings in 2023.) I was already juggling a bunch of projects, but I had a gut reaction to the poem This Page is an Occupied Territory, and felt an urgency to work on it. The title alone calls for a graphic treatment, so I started visualizing the text, which didn’t want to be contained within a standard book dimension. It grew in size, like the expanding war, and the daily bombardment of devastating news felt so outsized and all-encompassing, I had the idea of doing it as a tabloid-sized, newspaper-like publication. Adeena liked the parallel to the news, too, and because handling newspapers can be overwhelming—managing your body in this oversized thing, figuring out how to fold it and store it. I had seen online promotions for newspaperclub.com, based in the U.K., and started working with them. The proofs took a while, but once we were ready to roll, the run was printed in Glasgow, Scotland, on a Monday, and amazingly, we had all 700 copies in Brooklyn, New York, the next day, well in time for a live event at Pratt Institute the following week. I love that turnaround time and being able to sell it for 10 bucks a copy. And the printed piece functions well as a large-format, unbound score for the performance. At that first live event I page-turned a copy that faced the audience while Adeena performed the very sonic poem in her inimitable, turbo-charged way.

To get even deeper than intent, since this is partly supported by the Jewish Heritage Museum, what is the message here regarding the occupied territories and the war? Are you setting forth an argument for or against occupation, or is there another arc that you and Karasick are making into art?

Before I ever saw the poem, Adeena presented a live performance of This Page is an Occupied Territory in February 2024 at the Museum of Jewish Heritage: A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, as part of a “Poetry Reading in Response to Antisemitism.” Adeena and I are both Jewish. I think it’s fair to say Adeena embraces her Jewishness more than I do, in her life and her art, and feels a stronger connection to Israel. For as long as I can remember, I have been expressing my connection to Israel by protesting its overkill military operations and its occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. I’ve done this as a Jewish American who believes in Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish homeland and a democratic state for all its inhabitants, alongside a Palestinian state.

I was horrified by the Oct 7th Hamas attacks/massacre of a music festival and several kibbutzim, which left 1,200 dead, hundreds taken hostage, many wounded, and all of Israel in a state of shock. One of my heroes, Vivian Silver, was killed that day at her home in Kibbutz Be’er. Ironically, Vivian was one of the founders of Women Wage Peace, perhaps the largest grassroots peace organization in Israel, founded by Palestinian and Israeli women dedicated to finding peaceful solutions to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. She was 74 years old.

Israel has a right to defend itself but, in my opinion, Netanyahu and his war cabinet’s response has been completely disproportionate, unrelenting and brutal. The war they’re waging is clearly not just a matter of going after Hamas. It’s a policy of destroying the entire infrastructure of Gaza and killing tens of thousands of civilians, mothers, children, doctors, teachers, journalists. It sure looks like ethnic cleansing to me, whatever term you want to use for mass slaughter and making it impossible for an entire group of people to live in their homeland.

In June of this year, I came out with Jericho’s Daughter, my anti-war, feminist retelling of the biblical tale of Rahab, which I discussed with you and Debbie Millman on the May 16th PRINT Book Club. Even though I was already in prepress for that book before the Oct. 7th attacks and the retaliatory war, the text of that book spoke to the moment and helped generate impassioned conversations. My version of Rahab features her in a dialogue with two Israelite soldiers, in which, among other things, she says, “…Another incomprehensible war will be waged in the name of Justice. And thousands of other children will be sacrificed in the name of Life. Who is going to stop this wheel of death? I’m asking you, who?”

Sadly, the wheel keeps turning.

So, This Page is an Occupied Territory is my second publication in six months that addresses this f’n war, albeit in rather different ways. I won’t speak for Adeena, but I can tell you I was drawn to her poem because it seems to come from a place that acknowledges the different worldviews that collide in that small piece of land. On the back page description of the project, Adeena analogizes the occupation and control of a region by force to the process of translation, which can sometimes be “a form of occupation, whereby one language layered onto the body of another, is an act of war.”

She continues, “For the word ‘war,’ as both an English noun and a verb meaning ‘conflict’ and a German adjective [wàhr] meaning what’s ‘true, real, genuine’ literally places ‘war’ at war with itself. To wit, ‘wà[h]r’ not only ‘occupies’ the homography between the ear and the eye; the babelism at play between speech and writing—but born in ‘differance,’ madness and effacement, the notion of ‘occupation’ points to how what’s ‘true’ is always in conflict.”

Hence, we end up with a deadly conflict born of misinterpretations/colliding realities, and of course power imbalances, and so much history one poem or answer to a question can’t answer. I appreciate Adeena’s scholarly, poly-lingual investigation of a subject, and her exploratory and exploded use of language. As much as This Page reveals empathy for the complex realities and narratives of both sides, in the end, this poem is not neutral. It comes down against occupation and the horrors of a grossly lopsided war.

Back to visualizing. Is visualizing different, the same, or similar to illustration? Or is there some other experiential intent?

I have great reverence for “design,” and design processes, but when it comes to the design of language, especially books, I think the word “design” equates more with book covers. When it comes to the insides of books, let’s say text-laden books, design usually denotes a kind of packaging of the text, so that it’s functional of course, easy to read, clean, transparent, even stylish (well-designed), current, professional-looking. Maybe in zines, the design of the innards can be funky, edgy, elegant, name an adjective or way to dress a text up or down. But for me, since I come to design as a writer, it’s always been about the fusion of meaning and form. So, when I work with a poet who asked me to interpret their work, I prefer to use the word visualize.

I equate it to a filmmaker or theater artist or composer of opera adapting a preexisting text into a film or work of theater or music theater. It’s a meeting of minds and souls and sensibilities and the transformation of one kind of thing (a text) into another medium. And for me, I’m not going to go near a project unless I love the writing. That’s the source, the wellspring of whatever I’m going do with the visualization.

When it comes to creating imagery, instead of illustrating a text, I prefer to think of what I do as “illuminate” (shed light on, or contradict, add to) a piece of writing with visuals. I used the term “illuminated novel” to describe A Life In Books: The Rise and Fall of Bleu Mobley (2013), which contains 101 books within it. My author-protagonist’s books (book covers, catalog descriptions and excerpts that read like short stories) illuminate his life, and vice versa. I consider the images a part of the text. I also use the term “compose” to describe my writing and design process, as they often occur at the same time, and “composition” is the structural foundation of both writing and visual art, music too. With This Page is an Occupied Territory, I created a typographic landscape. The text and the image are one. There’s no separation as far as I’m concerned.

These terms may sound picky, but I can’t help but think about these descriptors before using readily available ones. In my first book, versations (1980), I wrote “realized by” before my name. I’m sure that was influenced by my early interest in contemporary music and “experimental” film and theater, where people used the word “realized” in a way that speaks to a kind of mysterious process that transcends the maker or makers, and speaks to interaction with materials, processes, intuition and god knows what else.

How do you go about visualizing? Is it intuitive, intellectual, aesthetic, symbolic—what is the process?

In the case of visualizing someone else’s poetry, I begin by reading and rereading the text. With Adeena Karasick’s poetry, that requires having encyclopedias and bilingual dictionaries at hand since she’s often sourcing many languages and plays with root words and etymologies, and is steeped in linguistics, philosophy, cultural criticism and history. As sonic and playful as her poems may seem at first, there’s a fair amount of study involved in reading her. Once I have a grasp of what the text is, for me, I do like to start the composition process with as blank a mind as possible. Put the first sentence or phrases on a page and see what starts to happen. The rhythms and pacing of the words are the most obvious starting point. But then, visual metaphors within the text start to suggest themselves. That involves making many iterations, and also mind mapping, which invariably leads to image research. In the case of This Page is an Occupied Territory, aerial photographs of occupied territories and war zones were helpful. Also, importantly, I try to feel what it might be like trapped inside an occupied territory, which in this case turns into an urban war zone.

This text, now publication, is also inherently meta or self-referential, as it speaks to occupied territories, not only throughout history (including open air ghettos in Poland and other Nazi-occupied countries), and of course in Gaza and the West Bank today, and other places around the globe, but also the occupied terrain of language itself, the very words on the page, which are occupied, by the writer, by me, by the reader, by typography, ink, paper, edges, intermingled vocabularies, the turning, stopping and starting of pages.

There is a build-up in the layouts and a rhythm that comes from the words and typographic composition. Can you describe what you’re trying to accomplish?

As much as I cherish that creative process of beginning with a blank slate and watching a work evolve through trial and error, sometimes you get a vision early on and you go with that. That’s what happened with This Page is an Occupied Territory. After reading the poem for the first time, I almost immediately had a vision for what it might look like, and that it would involve letterpress printing (a la Gutenberg) elements that could be used as blockades, barricades and border crossings. I made some sketches, working with the beginning of the poem, then I reached out to Roni Gross, a wonderful book artist and letterpress printer, and she ended up making prints for me of all sorts of wood-type characters, punctuation, dingbats, metal rules, borders and ornaments, Alpha Blox and wood “furniture” printed “type-high” on Vandercook letterpress proofing presses at the Center for Book Arts in New York City and the Center for Editions at SUNY Purchase.

I then made (digital) scans of the prints and visualized the poem in Adobe InDesign. The entire text—set in Knockout 71 Full Middleweight (a blocky, condensed weight of a large, muscular sans serif type family designed by Jonathan Hoefler and Tobias Frere-Jones)—lives within and around these inky, textured, bordered environments. The poem begins somewhat open-aired, with some room to move and wander around in, but as the poem progresses, the text and occupied spaces within this tabloid-size, 28-page publication become more and more boxed in, askew, and rubbled to pieces.

I think I know the answer to this, but I’d like to hear it from you: Does the publication serve as a “hymnal” or libretto for the poem by Karasick, or should/can it be read without the performative element?

Yes, yes, and yes. You know my work began as performance scores and graphically notated plays. Over time, as I became more serious as a writer and developed more awareness of the different attributes of different mediums, I stopped putting stage directions and music notation in my books. But performance has continued to be an important part of my oeuvre. It’s one of the things that draws me to Adeena’s work. She’s a dynamic, force-of-nature performer, and it’s a kick watching her perform off of my rendering of her words, yes, as a kind of shaped-note hymnal for her incantations. But also, the publication serves as a score for the reader, either to be read silently to themselves, or out loud, or, as I mentioned before, reading along as they’re watching Adeena perform it live, with me or on her own.

We printed a QR code in the back of the Ouvert Oeuvre: Openings book, so after reading the book to themselves, the reader can read along to a recording of Adeena accompanied by Grammy Award–winning musician Frank London. I’ve also made books that came with audio CDs or were augmented by animations, and I recently came out with my first fully electronic book (Riveted in the Word), which has kinetic typography and an audio soundtrack. But the scale, immediacy and performative energy of This Page is an Occupied Territory I don’t think warranted any augmentation.

Finally, for anyone who knows Werkman’s The Next Call, there seems to be an homage here. Is this a conscious “remembrance”?

Yes, the ghost of Werkman (1882–1945) was hovering around this project from that initial vision I had of printing wood “furniture” normally used (but not seen) to lock up type and other printed elements to the bed of a press. Looking at reprints of The Next Call was definitely part of my visual research, appreciating the raw energy and improvisatory joie de vivre in his typographic, often hand-brayered compositions, many of which were composed during very trying times. I actually replicated a fragment of a 1934 “Komposition” of his made of interlocking parallel lines and rectangles that I use as a motif that appears here and there throughout This Page is an Occupied Territory. It’s really the only time I can remember ever using a visual quote like that from someone else’s work. Perhaps you picked up on it. You know, in those last years of his life, not only was he an outspoken partisan, but he also worked on “illustrating” a series of Hassidic stories from Baal Shem Tov, a bold act of resistance itself. Talk about chutzpah!

The post The Daily Heller: A New Visualized Poem Covers ‘Occupied Territory’ appeared first on PRINT Magazine.