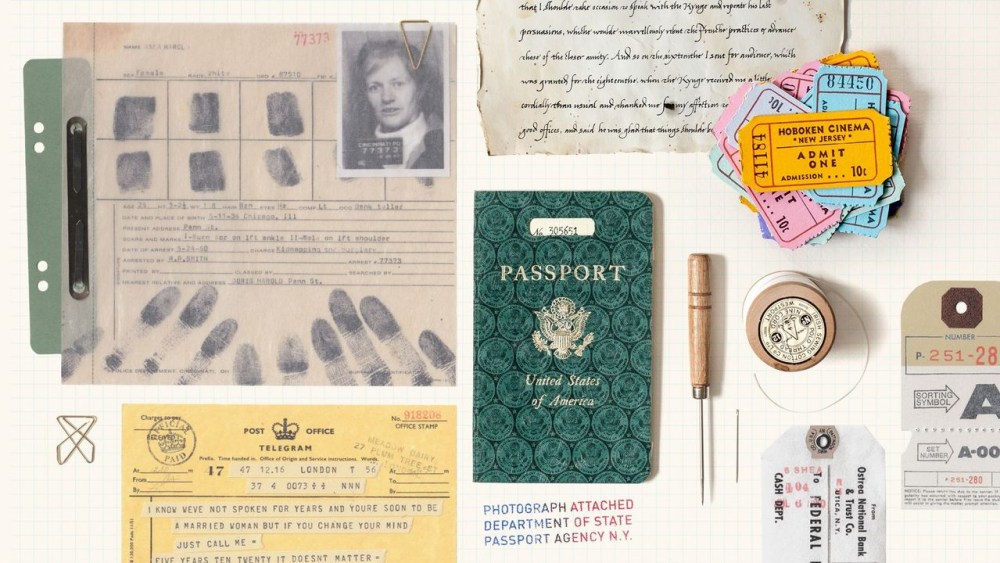

Annie Atkins has made a name for herself as one of the most skilled graphic prop designers working today. Her most impressive feat in the film industry has been working alongside none other than lauded director Wes Anderson, bringing the meticulously handcrafted and immersively detailed worlds of his films to life. She designed graphic props and set pieces for Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)—most notably creating the famous Mendl’s Patisserie Box—and miniature props for his stop-motion feature Isle of Dogs (2018).

Having mastered the art of graphic props and setting the gold standard for the industry, the Dublin-based Atkins recently decided to explore a new avenue: the wonderful world of children’s books.

Released in October and available now for the Christmas season, Atkins’ first-ever children’s book, Letters from the North Pole, is geared toward kids yet engaging for readers of all ages, due to her signature level of craft and keen design eye. The interactive hardcover book features gold foil embossing on the front cover, and five letters from Santa Claus inside that children are meant to pull out from envelop-pages to read and enjoy.

The concept of the book is perfectly suited for Atkins’ skillsets as a graphic prop designer, specifically tapping into her ability to make props for the letters from Santa. Atkins also has a background in writing, having previously published a book of poems and then a book about her practice as a prop designer, Fake Love Letters, Forged Telegrams, and Prison Escape Maps, in 2020.

In this way, Atkins was precisely the person to envision and execute Letters from the North Pole. I spoke to Atkins to learn more about her background in prop design for film, how that informed her experience of writing and designing this book, and to glean more intimate details about the book itself. Our conversation is below, lightly edited for clarity and length.

As a sign painter myself, I’d love to hear more about the influence of sign painting on your work as a prop designer. You recently posted a lesson you’ve imparted at design conferences on your Instagram, which read: “How I stopped designing like a designer and started thinking like a mediocre sign painter in the rain.” Can you share more about this?

I always think that one day, when I quit my job, I’m going to retrain as a sign painter. The reality is, I’m not a sign painter at all. I’m not really good at any one thing, I’m a little bit good at lots of different things. I copy sign painters, I copy lettering artists, I copy old typewriters. So much of my work in film is about being able to imitate a certain look, but not necessarily about being an expert in that area. I would love to do sign painting properly, but I never have done, actually.

I love making lettering for film sets. The way I do it for film is I draw the lettering, either hand lettering or using type, and then I will hand those drawings over to professional sign painters, and then they paint it for me. Because I’ve done so much of that, I’ve really fallen in love with sign painting.

A lot of the time, you don’t actually want it to look like it was painted by the best sign painter in town. It’s supposed to often look like it was painted by the guy who owns the shop or the person who’s made a handmade poster and stuck it up on the street. A lot of this stuff is supposed to look like it’s come from the vernacular rather than from professional experts. That’s really fun because you can play with that. You can do things that are supposed to look a little bit naïve and homemade, but they’re still supposed to feel pretty. We’re designing things for film, and you’re asking an audience to sit down in front of the cinema screen for two hours, so you want things to have a certain aesthetic appeal to them as well.

It’s like your work reflects the off-screen characters, who may not be visible in the film but still make up the movie’s universe. The character is only present through how you’ve portrayed their sign. That’s such a deep-seated layer of the details that go into a movie.

You have to get into character for everything you make. Most of those things you’re making are not for characters in the movie. It’s for the people who own the shops in the background of the movie, the chemists who put the labels on their old poison bottles, that kind of thing.

Why did you want to go from this world of film graphic design to that of children’s books?

I’ve been interested in children’s books for a long, long time because I loved them as a child, but also because we read so many of them now in the house with my two little kids— they’re three and eight.

I had always been interested in making a children’s book, but I’m not an illustrator, I’m a graphic designer and a writer. It had never really occurred to me to make my own children’s book, but then Magic Cat came to me with this idea they’d had about a book about letters to Santa Claus, and they asked me if I would design the letters that Santa writes. Of course, that’s totally up my street because it’s the kind of thing I do for film all the time, so I was immediately interested.

It also happened to be last year during the writers’ strike, so there wasn’t a lot of shooting going on, and I wasn’t on a movie at all for the first time in ages. So I had loads of time, and I really wanted to write the book as well, so that’s how it ended up coming about. I wrote the book and designed all the props and graphic bits and pieces, and then worked with the illustrator Fia Tobig who drew all of the beautiful pictures of the children.

What was the writing aspect of the book like for you? Was that also uncharted waters?

I have written quite a lot over the years in a kind of personal way. I wrote a book of non-fiction about graphic design in film a few years ago, and years and years ago, I wrote a personal blog and some poetry— I had a couple of poems published a decade ago. So, in a small sense, I had written quite a bit before, but I had never written for children, so that was a first.

It was really fun because I had to write in Santa’s voice, and I decided that Santa Claus would always write in rhyme. So then I had to write rhyme in verse as well, which was a good, tricky experience.

Each of the children in the book has a different voice too, in how you’ve written their letters to Santa.

I suppose I have experience in that from film work. When you make props in a movie, nobody is really writing the content for you. Sometimes, you can take a little bit from the script, but a lot of the time, graphic designers making film props have to create that content themselves. So I have written fake love letters, telegrams, little notes that characters have to pass between each other; all that stuff needs to be written. I had always really enjoyed that, I love writing content for things.

You mentioned that you read all the time to your children, and grew up loving children’s books. What are some of your favorite titles and authors that maybe inspired you for elements of Letters from the North Pole?

I drew heavily from Janet and Allan Ahlberg who wrote countless books. They wrote a book called The Jolly Postman, which this book borrows from quite a lot because it has all the pull-out letters. I always loved reading those books as a kid, and I read them now to my kids as well, because I love reading books that rhyme, and I think the kids love it as well. There’s just something really lovely about this wholly unexpected rhyme at the end of a sentence.

I love Benji Davies books: The Storm Whale, all the Bizzy Bear books. I read loads and loads of Shirley Hughes as a kid, and, again, I read all of those books to my kids now. But those books are all quite old now, they’re like, 40 years old.

There’s something so beautiful about how children’s books can be so timeless because so many important themes and lessons about life in many children’s books transcend generations. I also love how the physical copies of the books we read as children we can read to our kids one day. We pass them down as a sort of heirloom.

Absolutely, I did want to write something that felt timeless. I don’t think I was overly conscious of it, but certainly, all the books that we love here in the house feel timeless.

Life has changed drastically for kids over the years, but certain bigger-picture ideas, like being a good person, that are often reflected in children’s books, remain the same. I think Santa is timeless, and the idea of sending letters to the North Pole is timeless.

I really wanted to make a book that was like an introduction to Santa Claus, that kind of went back to basics. We only know so much about Santa. When I was a kid, I started questioning his existence, like, How does he get around the world in one night? Don’t his reindeer get tired? If I stay up late will I meet him? I remember my mother always had the same answer for me. She always said, “There’ve been a lot of books about Santa Claus, there’ve been a lot of songs written about Santa Claus, but the truth is, nobody knows what Santa looks like, because nobody has ever seen Santa in real life.”

That was what I needed to keep the magic alive, it was the not knowing. So with the book, I really wanted to do that; to give the kids that are reading it just enough information so that they’d be hooked into the mystery of it all. When the kids ask the questions in the book, Santa just deftly bats away the questions with these answers. I think that sometimes the less you say, the more magic it is.

I think the rhyming is part of that too. There’s just something sort of magical about rhyming, in a way, and that ties into the Santa mystique you’ve created with his character.

When I was little, my grandfather used to write me letters; he typed them on his typewriter, and they always rhymed. Rhyming makes it more magical somehow. I suppose it’s a cover-up, too, isn’t it? Santa is actually just your parents, but if they make it a little more whimsical it’s less likely you’ll be like, Hang on a minute, that’s you!

I know your film graphic design work, a lot of the process involves tons of historical research; looking at old artifacts and archives to accurately recreate them. What kind of research went into the designed elements for this book, especially in terms of the letters, their postage, and the diagrams for the toys illustrated in them?

I went looking for loads of old vintage letters. At first, I was going to write Santa’s letters as handwriting, so I was looking for a kind of handwriting style that would feel like it came from this elderly gentleman in the North Pole, but it also had to be legible for children to be able to read it. In the end, I settled on a typewriter instead, because it felt right to me that Santa would have his own typewriter, and it also made it super legible.

You get those ideas by looking at real things. I have a collection of old letters that I’ve found or bought over the years, and I’ll go through my boxes of stuff, and I’ll cherry-pick all the little bits that make sense. Handwriting varies so much from different people and different times. One of the things we run up against in film is legibility, because older handwriting, cursive handwriting, is actually very difficult to read now. I did do some handwriting in the book for the envelopes. I made that handwriting quite calligraphic and fancy for the envelopes that Santa had addressed to the kids. That felt like a good place to do it because there isn’t too much text there that needs to be read.

Each of the gifts that the children are asking for in their letters to Santa are so unique, clever, and fun. How did you come up with those?

I wanted them to be inventions that children think up. The children were going to think of their own toy invention that they wanted Santa to put into production in his workshop for them. So things like a detective’s briefcase that’s full of disguises, and a teddy cam, and fake nose and glasses so that kids could start their own private investigator business, a robot who tidies your bedroom— you couldn’t make a book like this without a bedroom-tidying robot, because that must be one of the most useful things you could have as a child.

The toy ideas in concept are so much more interesting than a doll or a football, but they also make for much more visually compelling illustrations. All of the diagrams and figures are so detailed and rich. The toy ideas invite much more exciting visual representation and exploration.

Yeah, I wanted them to be inventions that Santa would then have to get one of his industrious elves in his workshop to draw up, and he would have to make a proper technical drawing of this invention, like a blueprint.

These toy inventions and their production definitely add to that sense of magic you’re trying to capture throughout the book. They have a sort of magical realism to them.

Exactly. When I first started coming up with this idea, I thought that the children would do drawings of their invention, but then it just felt more fun if the kids had the idea, and Santa had them drawn up. I thought that that would help spark the reason for imagination. I’m hoping that when a kid is reading this book, they’ll start thinking, Oh, what would I invent? If I was going to ask Santa to put something into production, what would I want?

When I was writing and designing this book, I was constantly thinking of the child that it was being read to, and what the kid would like, and what kind of drawings the kids would like, what kinds of toys they would like to think about.

Can you point to a favorite design detail or easter egg in the book that you’re particularly proud of?

When I first started designing the book, one of the things that I was really thinking about was not wanting to give away too much about Santa to keep the mystery alive. So I decided that we wouldn’t show Santa in the book at all, except for in the postage stamps. Santa is someone who often appears on postage stamps, especially vintage ones, so I think it’s kind of nice that he’s just there on the stamps. I thought that was a nice way to show him without really showing him. It just keeps him that little bit enigmatic. You don’t actually see him anywhere else in the book until the very last page when you see him silhouetted in the doorway of the workshop, and then on the vignette you see him flying off in the distance with his reindeer.

When working in film, you’re really just working to a script. You’re making everything that’s required of the film script. There is room for creativity there as well, you have to film in the gaps a lot of the time, but this felt very different to me. I had to think in a much more creative way for this, and it felt much more personal as well.

The post Graphic Prop Designer Annie Atkins Takes her Talents to the World of Children’s Books appeared first on PRINT Magazine.