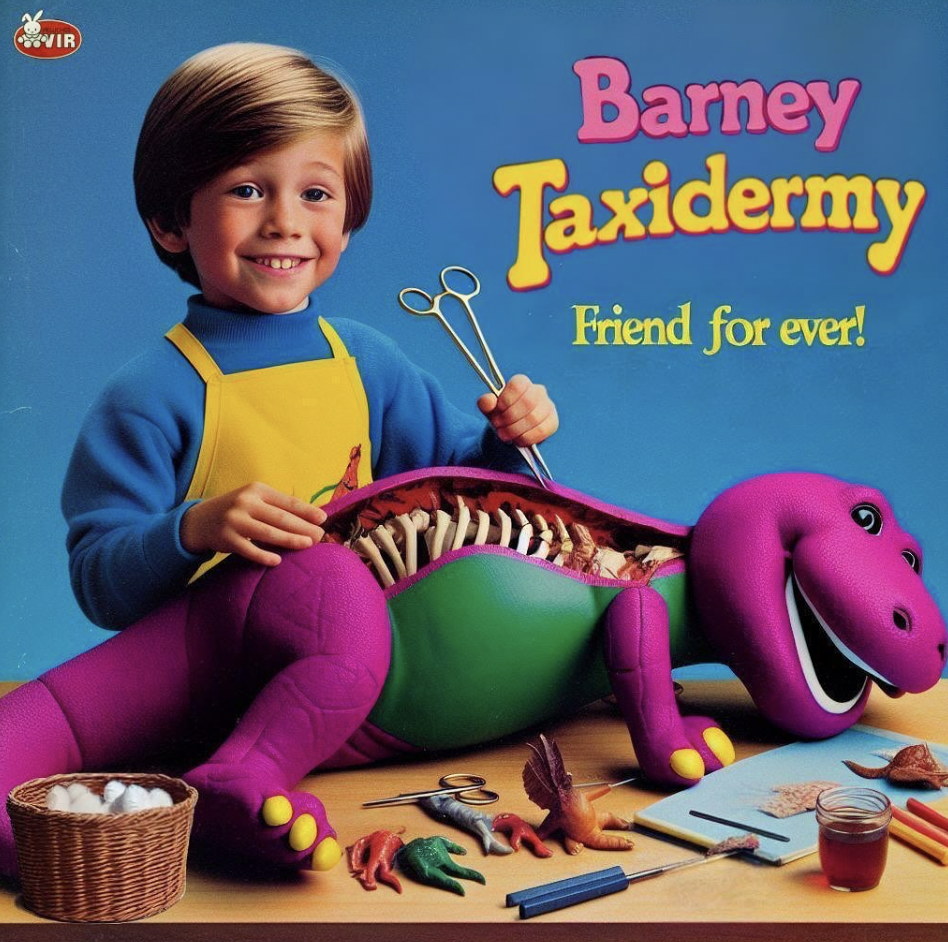

It’s quite possible that while embarking upon your daily doom scroll on Instagram, you’ll come across the Barney Taxidermy kit by Vir. Or maybe you’ll encounter Life Support Elmo by Fisher-Price, the My Little Sweatshop kit by Feber, or, best of all, Pregnant Ken by Mattel. If you do, congratulations! You have been sucked into the twisted world of Forbidden Toys, from the brilliantly maniacal mind of the artist known as Rosemberg.

While these perverse toys might look real at first, they are, in fact, figments of Rosemberg’s imagination, visualized through AI software. Using the style of 90s toy advertisements and packaging, the Forbidden Toys project deploys dark humor to poke fun at commercialism and the toy industry. But first and foremost, it’s clear that Rosemberg is just having a laugh. The artist was kind enough to answer a few of my questions about their Forbidden Toys series, shedding light on their background, process, and the use of AI in the arts. Their responses are below.

What’s your art background?

I have formal academic training in photography and film, but I’ve spent my entire life irresistibly absorbed by artistic creation in its most diverse forms: literature, drawing, design, music…

A few years ago, I began exploring creation from a conceptual perspective, which led me to leave modified works and toys out on the streets. That conceptual exploration eventually gave birth to the project we’re discussing today: Forbidden Toys.

That said, I consider the art I made as a young child to be part of the overall corpus of my work. I’m still inventing stories and drawing monsters.

Water Fun

Where did the idea for your Forbidden Toys series come from? How did that develop into what it is today?

Toys have always been present in my work in one way or another (in addition to being an avid collector of toys and peculiar objects), so the idea was always there.

I’ve always been deeply fascinated by the evolution of AI, and I vividly remember how awestruck I was the first day I tried DALL-E mini and asked it to generate 1960s-style laser guns. While the results weren’t realistic yet, they were precise enough to make it clear that it could be used as a creative tool in the future.

During a particularly stressful period when I barely left the house, I developed the Forbidden Toys project, which continues to serve as a form of therapy to this day. As the project gained popularity, I began refining the images and producing real objects, which is where the project currently stands.

What AI software do you use for Forbidden Toys? What are your general thoughts on AI usage in the art world?

I currently use several: MidJourney, DALL-E 3, Runway, and Wand, depending on my specific needs. I then mix and finalize everything traditionally using Procreate or Photoshop.

Naturally, I support the indiscriminate use of AI, just as I support any tool that an artist can use to express themselves. The controversy around using copyrighted material to train AI models feels distant to me because of my contradictory reluctance to fully accept copyright as a legitimate right. That said, just as generating illustrations or designs doesn’t make you an illustrator or designer, it does allow you to materialize concepts, which is, by definition, an act of conceptual creation.

The eternal post-Duchamp debate on authorship and what qualifies as art is as stimulating as it is repetitive. This debate has been unconsciously revived with the popularity of AI, and though it’s framed from a new perspective, it’s the same old argument. It’s true that this technology will inevitably create casualties, as always happens with groundbreaking tools; particularly among certain technical jobs and commission artists whose styles are easily imitated.

However, the debate is irresolvable, and it will always be fascinating to read theoretical frameworks that supposedly distinguish art from what isn’t.

The eternal post-Duchamp debate on authorship and what qualifies as art is as stimulating as it is repetitive. This debate has been unconsciously revived with the popularity of AI, and though it’s framed from a new perspective, it’s the same old argument.

What’s your typical process like for developing your ideas for each Forbidden Toy?

The initial process is identical to any other artistic project I’ve undertaken; I always carry a notebook where I jot down ideas and sketches. This essentially gives you an extension of your brain with a prodigious memory; anything can inspire an idea.

Once I’ve determined that a concept is interesting, the first thing I do is draw it to get a sense of what I’m looking for. After establishing a clear vision, I move on to wrestling with AI to generate the necessary elements. Working with AI is like dealing with a half-deaf art department since my ideas are often very specific and leave little room for abstraction; the process can be as tedious as it is inspiring. With all the required elements prepared, the most labor-intensive part of the process begins: combining everything traditionally in an image editor, where I fix errors, finalize the texts, and refine the overall composition.

Much like making a film, the final result always diverges from the initial mental image you had. Your job is to approximate that vision, and the important thing is that the narrative and message are expressed in the way you intended.

Which of your Forbidden Toys is your favorite? Is there a particular Forbidden Toy that you feel encapsulates what you’re trying to do with the project the best?

It’s hard to pick just one because, beyond each having unique characteristics, they’re all part of the same project, so my preference is purely personal. I’d say my favorite is “Zappy” because it marked a turning point in how precisely I could convey my ideas.

The toy I think best encapsulates what I’m trying to achieve with the project is undoubtedly “Pregnant Ken.” For some inexplicable reason, it caught the attention of a Cypriot MP who turned it into a scandal and got fact-checking agencies investigating the image’s origins. The whole fiasco culminated in an official statement from Mattel denying any connection to “Pregnant Ken.”

Naturally, I’ve got the statement framed at home as a trophy.

What are you trying to communicate or say as an artist with the Forbidden Toys series? What sort of experience do you hope your followers have with your creations?

At its core, I aim to open a window into a nonexistent past and provoke the kind of reactions that would arise if these objects were real. Toys are a medium we all know, and that shape our personalities, always leaving a residue of identification that is fascinating to play with. By presenting objects with a familiar context but grotesque essence, an inevitable comparison to reality occurs, leading to thoughts I find deeply engaging: Is this real? How does it work? Who in their right mind would think of something like this?

These reactions are the essence of what I aim to convey because they forcibly stimulate a subverted reflection on the concept itself. At the same time, they can serve as a commentary on censorship, ideology, taboo, governance, and the weight that advertising language carries within them.

In a way, I compel viewers to recreate the experience of wandering through a bazaar and stumbling across a Bin Laden action figure from a Western perspective.

My followers generally fall into three main categories: those who appreciate the artistic value and understand the project, those who interpret it as purely humorous, and (my personal favorites) those who believe the toys are real.

All of them are right.

The post The ‘Forbidden Toys’ Series Proves that There is a Place for AI in the Arts appeared first on PRINT Magazine.