War never instantly ends exactly at a fixed ceasefire time without the combatants leaving even more death in their wake. The Second World War did not cease entirely when Nazi Germany signed the terms of unconditional surrender in 1945. To the victors go the spoils. And those spoils can damage or destroy untold numbers innocent people’s lives.

Case in point: As part of the 1940 Nazi-Soviet nonaggression pact, the USSR invaded and occupied Estonia and deported its “anti-Soviet-elements” to remote eastern areas deep inside Russia. When the pact was broken in 1941 with Hitler’s surprise invasion of the USSR, rather than “liberate” Estonia the Germans besieged and occupied it, imposing their own brand of terror. During the deadly match-up of battling armies, Estonian civilians were caught in the middle. In 1944 when the Red Army reconquered the Baltic states, including Estonia, Stalin’s terror ensued. Thousands of civilians fled the advancing troops, some escaped to Sweden, Finland, Germany, Poland, Canada, England and the USA.

Maria Spann is a Brooklyn-based photographer whose maternal grandparents fled to Sweden along with their two young children — Maria’s 5-year-old mother and 7-year-old uncle. In her youth Maria listened to her grandparents’ harrowing accounts and decided to delve deeper into this little known horror of the world war, of the Estonian exodus.

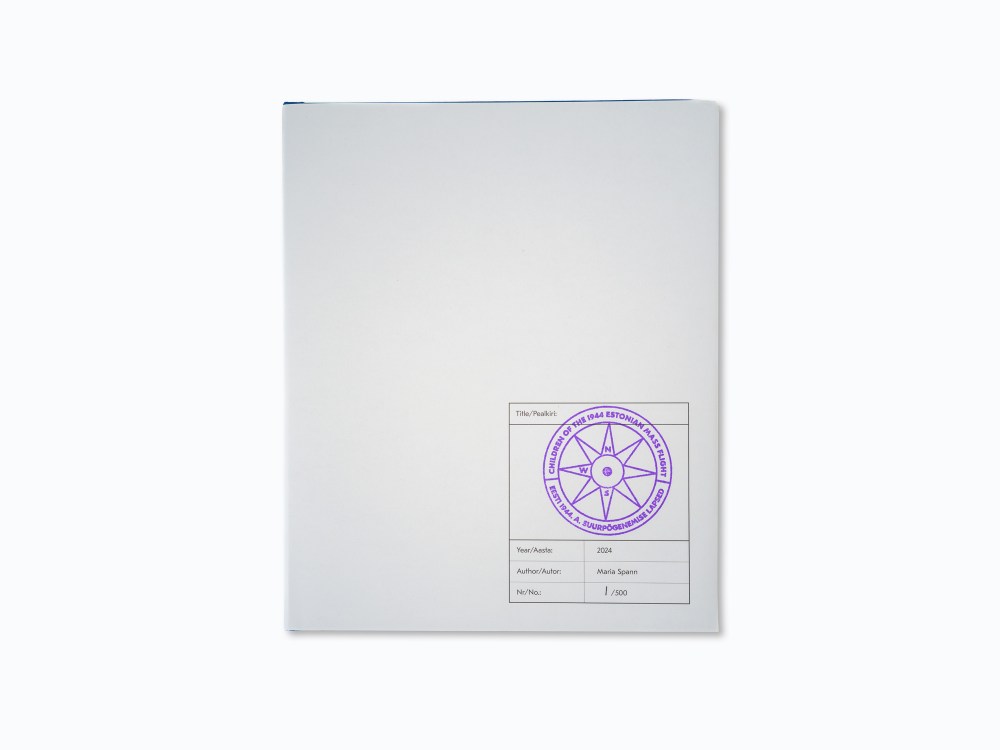

Her concept: To interview as many survivors as possible who were children then from her mother’s generation, photograph them now as older people along with one object that they saved from the journey. Her work has recently been compiled into the limited edition book Children of the 1944 Estonian Mass Flight, which Maria also handsomely designed and skillfully self-published. Each section begins with a compelling personal recollection on the first of two spreads (in English and Latvian) and a portrait on one page and the object on the opposite.

For this interview she talks about the process of tracking down the first 57 survivors, and recording their memories in what promises to be an ongoing discovery.

Jacket and cover of “Children of the 1944 Estonian Mass Flight”.

What triggered this emotional project?

I’m half Estonian. My mother lIme and uncle Jüri were born on a farm in Nautse on the small island of Muhu in Estonia. They were 5 and 7 years old when they were smuggled with their mother Siina onto the boat Juhan, which made nine journeys from Tallinn to Stockholm during the late summer and fall of 1944 (to transport ethnic Swedes from Estonia to their ancient homeland). Their father Georg made his way over a few weeks later in a small rowing boat with three other men.

During my childhood I heard the story of their escape mostly from an adult point of view, but always wondered what it was like for the children. Later on, when my grandparents had passed away and my mother and uncle were the only “real” Estonians left in our family with memories of Estonia and the escape from there, I became fascinated by how different their account of events was from the (very few) stories my grandparents had told us.

So, I decided to start a photographic project—I wanted to try to find more people who fled Estonia as children, just like my mother and uncle, and hear their accounts of the escape.

How often and for how long did you visit Estonia during the course of your research?

Not once! All my subjects still live outside of Estonia, apart from a few who have second homes there. Rather pleasingly though, the book was printed in Tallinn, and I went there to pass it on press this summer.

How did you find the people in this diaspora? And where did many of them reside now?

I started with my mom and uncle, of course, as they were easily accessible to me in Sweden and it meant I had something of the project to show when reaching out to others. Then I contacted the Estonian Houses (centers of Estonian culture set up in various places across the world, many after the mass flight) in Stockholm, Gothenburg and New York City to explain my project and see if they might have possible candidates in their communities.

In Sweden, news spread really fast by word of mouth—once I’d seen a couple of people, they recommended other friends and acquaintances and most were keen to take part. In New York, I attended the Estonian Cultural Days in 2018 to hand out flyers and spread news about the project. It took a little longer than in Sweden, but again, most people were eventually keen to take part. I also contacted the VEMU Estonian Museum in Toronto, where there is a huge Estonian community, and they put me in touch with an Estonian retirement home in the city.

The main 10 countries where the Estonian refugees ended up resettling were Sweden, UK, France, Belgium, Australia, USA, Argentina, Venezuela and Brazil. My initial aim was to travel to all these countries to be able to include a chapter on each in the book. However, financial constraints as well as COVID got in my way and so I decided to focus on the countries I could easily get to in order to finish the book by the 80th anniversary of the flight this year. In early 2023, I contacted various Estonian Houses around the UK, and quickly found a group of willing Estonian refugee “children” who I met with during a week-long whirlwind tour of England.

What was it that you wanted your subjects to provide to you? What is the significance of the objects that are shown?

I wanted to hear the stories of the escape from a child’s point of view. The adult accounts are mostly accurate in a factual sense, but for the children, it was more about strong sensory memories—the smell of the boat, the taste of the white bread or the sinking feeling in their stomach—than the actual events of the journey itself. Often my subjects would say something along the lines of, “Oh, but what do I know—I was just a small child. It’s not the real story!” But I think that’s exactly what it is. The objects were added as a way of making the project more visual and showing what a wide range of belongings different people hold onto from such a momentous life event.

What were the lasting lessons you learned from talking to all of these people?

I have met with 57 people for the project, and I found it so interesting how what you remember as a 5-year-old differs greatly from what you remember as a 15-year-old. Most of the people who were aged between 3 to 9 years old when they fled remember feeling worried and didn’t really know what was happening, but were also safe in the knowledge that they were with their families. Quite a few 10- to 14-year-olds were excited to finally be traveling somewhere, as they hadn’t been able to do so since before the war. One lady who was 13 at the time of the escape was just extremely relieved that they couldn’t take their piano with them as she hated practicing. But many of the older teens I met were left much more traumatized and often didn’t really want to share too much.

I also think these stories are hugely relevant today—nothing has really changed in terms of children being forced to flee persecution all over the world. Maybe sharing these now … can contribute to more empathy being shown towards today’s refugee children and their families.

You produced and published the book yourself. How will you distribute it, and who do you want to have a copy?

Oh yes, the distribution and PR for the book is my least-favorite part! I managed to secure funding for the printing costs of the book from a few generous institutions in the Estonian diaspora, and in exchange I sent them copies of the finished book, which I hope will help spread the word. It is also being sold at the Vabamu Museum of Occupations in Tallinn and through the Estonian National Archives in Tartu. Everyone who contributed their story to the project has received a copy of the book. I’m also selling it through the project website.

If I’m allowed to dream, I would love this project to eventually end up at the Fotografiska Museum in Tallinn—back home!

The post The Daily Heller: Memories of a Wartime Escape From Estonia appeared first on PRINT Magazine.