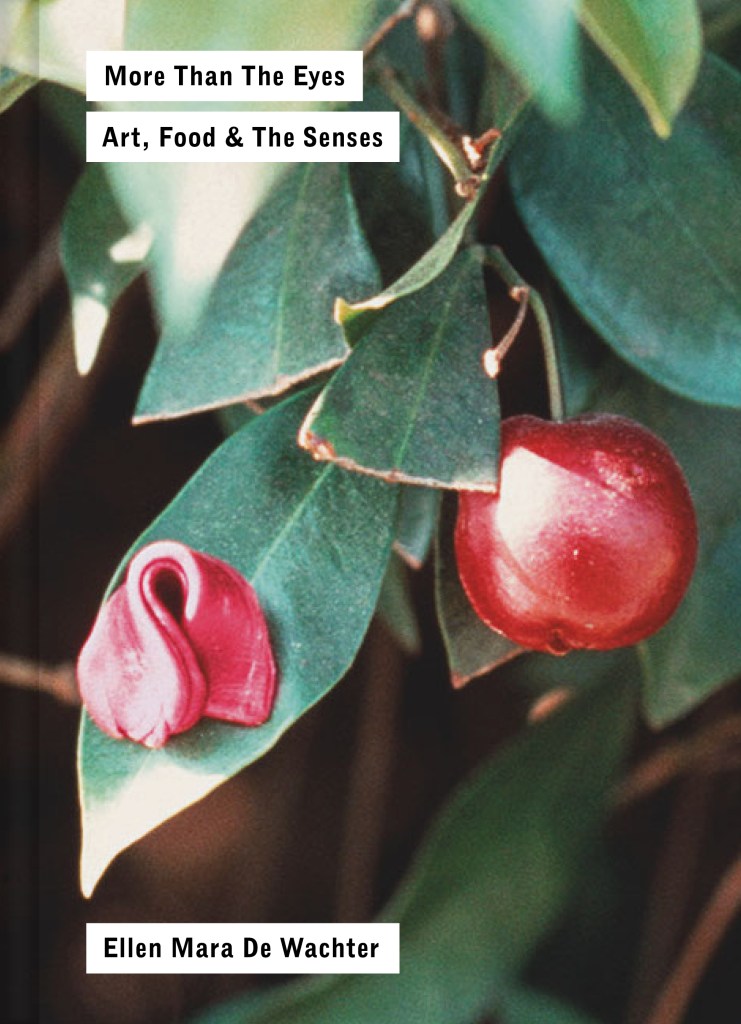

What is more essential for life than food? Not surprisingly, it is nourishment for more than the body, but the soul too — and the fuel of art and culture, tradition and religion for all tastes. In More Than the Eyes: Art Food & the Senses (Atelier Éditions/D.A.P) Ellen Mara De Wachter, a London-based author of Co-Art: Artists on Creative Collaboration and the coauthor of Great Women Artists, considers how food confronts, subverts and ultimately brings us to our senses. Set between 1960 and 2000, the book addresses how putting food at the center of the highly visual art world, the artists in this book quicken a range of sensations “beyond visual perception, helping us access and liberate aspects of our experience that have been ignored or suppressed.” Topics include Carolee Schneemann’s performance pieces using meat; the way in which Hannah Wilke rejects the imperative for women to be “sweet”; Zoe Leonard’s exploration of decomposition as process; Adrian Piper’s conceptual work incorporating hamburgers; the SoHo artists’ restaurant FOOD; Agnes Denes’ wheat field near Wall Street; and how other artists, such as Sarah Lucas and Andy Warhol, introduce the iconography, foods and desires of the working class into the rarefied environment of the gallery and museum.

I asked De Wachter to whet our appetites for learning more about the inter-relationship(s) between art and and the range of consumables that we cannot live without. Hmmmmmmm!

What was the trigger for this book about food and art? Are you that dreaded word, “a foodie”?

The short answer is that when I completed my first book, Co-Art: Artists on Creative Collaboration, I thought to myself, “what shall I write about next?… What are my favorite things?” They are art and food, so I thought, “I’ll do that.” What was interesting was that there was very little writing exploring the crossover between art and food. Very quickly I realized that I was specifically interested in what happens when artists use food as a material, rather than as image or a theme. Something really unusual and exciting happens when food is introduced into the arena of art, and into the space of the gallery or museum.

Would you say that food is the epitome of consumable or commercial art?

Not all of the artworks I discuss in the book use food as something to be eaten. Food is used as sculpture, as props for performance, and as a way to interact with an audience, but only sometimes as food intended to be eaten. So I would not say it’s the epitome of consumable art. And as for the commercial aspect, most of this work was highly experimental when it was made; the book covers the period from the 1960s to today, and in only a few cases have such works achieved art market success.

You say in your introduction that food in art excites more than the appetite but political and social concerns. How does this play out through the essays in your book?

Food is an essential part of daily life all around the world. It is used to perform rituals, to express and preserve identity and to bring communities together. It carries so much meaning, sentiment and power. So it’s never not political, and in each case I look at in the book, the artist has selected particular foods to work with and drawn out their significance in unique ways. Underlying my research into each of these examples is my interest in the way food as a material in the arena of art invites us to become more aware of our bodies and senses. My research into the hierarchy of the senses that operates in western culture has been fundamental to my understanding of why these art works are so powerful and affecting. In this hierarchy, which we have inherited from the Enlightenment, sight and reason are positioned above all the other bodily senses. The so-called ‘lower’ senses are ostracised and neglected, and we end up with a situation in which many of us are detached from our bodies’ full sensorial capacity. I think art that uses food as a medium helps us connect back with the range of sensations beyond the visual and rational, and I think this is radical and inspiring.

Will you shed a light on Adrian Piper’s “Power is Bad for the Lining of the Stomach”?

Since early on in her career, Adrian Piper has called out the detrimental effects of the commerce of art on the body–mind–spirit complex, writing about how the dynamics of public interactions, politics, and economic status lodge in the body. She memorably did this in her 1973 text “A Political Statement”, which reads “Power is bad for the lining of the stomach. Financial success causes overweight and heart trouble. Art-world parties are bad for the liver. Galleries cause headaches and blood-sugar attacks. Dealers cause dislocation of the jaw. Critical reviews cause digestive upsets and emphysema. Competition between fellow artists for any of the above is a known carcinogen.”

It is interesting to read Andy Warhol’s essay, after all his post-commercial art reputation is based on soup cans (and Brillo Boxes). Can you discuss why you selected his essay as good for your narrative?

I was interested in Warhol’s assertion that his life was his art. I thought, if a life is a work of art, food will necessarily play a part in this work of art. So I wanted to explore how food played a part in the art work that was his life. Added to that, Warhol was obsessed with food: the food he ate, the food he didn’t allow himself to eat, food he fantasized about, and food he depicted in his drawings, paintings, screen prints and sculptures. It was everywhere in his life/art. He spoke and wrote about food with poignancy and also with great humour. For example, in his recipe for cake in his 1977 book, ‘The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again’: “You take a piece of chocolate… and you take two slices of bread… and you put the candy in the middle and you make a sandwich out of it. And that would be cake”.

Star and rising star chefs have been claiming for decades that their respective dishes are art. Do you consider making food akin to making a work of art?

Yes, of course! It’s all in the intention. If you want your scrambled eggs to be art, I have no problem with that. It’s how you do it that matters. What are you trying to say, to do, to make me feel with those scrambled eggs?

The post The Daily Heller: Food That’s Not For Eating appeared first on PRINT Magazine.