Connecting Dots is a monthly column by writer Amy Cowen, inspired by her popular Substack, Illustrated Life. Each month, she’ll introduce a new creative postcard prompt. So, grab your supplies and update your mailing list! Play along and tag @print_mag and #postcardprompts on Instagram.

The clearest way into the universe is through a forest wilderness.

John Muir

A Network of Branches — Postcard No. 5

Where I live, most of the trees do not lose their leaves. Most, not all. There are benefits to living where we don’t really experience winter, but there is also something lost, something missing, in never seeing the tableaux of winter and its nakedness, its barrenness, and its lonely spaces.

I have spent countless hours through the years looking through the back window, through a gap in the trees, a wedge of space that acts as a viewfinder of sorts, framing a few houses on a hillside in the distance. I have watched the branches of the trees blow in the wind, watched the morning fog drift over and through, and sighed at pink and lavender skies in the distance. At twilight on a rainy day in winter, the trees are an inky green-black, impenetrable in spots, lacey in others, a heavy blue-grey hovering in the gaps. I have watched birds dart in and out and squirrels race along limbs. I hear an owl at night and know it must be nestled in one of these trees.

These are my trees, but I don’t know these trees.

I am always looking through or beyond or between. I don’t have a sense of the structure of these trees. I could not diagram their trunk. They are not classically beautiful. The leaves are not pretty. The overall shape of these trees is not willowy or elegant. The bark doesn’t turn gold or red or peel in lovely strips.

The trees are part of the magic of my treehouse view, and yet they often act as conduit, as filter, and as backdrop.

Looking Back

When I was in high school, I was given a book of Robert Frost poems and a volume of one hundred and one classic poems. For many years, I treasured the slim volume, words I then outgrew. They were not the type of poems I would go on to read and write, but at the time, they were a gateway for a young poet, a sad and lonely girl in the mountains.

In that thin volume, I held onto rhyming wisdom like:

Laugh, and the world laughs with you; Weep, and you weep alone.

Ella Wheeler Wilcox, “Solitude”

In so many ways, those words set the stage for the life to be.

Though they haven’t been looked at in years, these books have survived many rounds of decluttering (although, likely, they won’t make it through the next). They sit in a corner of a shelf, quiet markers of my past, of a time when everything stretched ahead.1

Joyce Kilmer’s poem, “Trees,” was in that volume of one hundred and one, too. Despite all we forget, there are some lines that never leave us.

I think that I shall never see a poem as lovely as a tree.

Joyce Kilmer

The Trees We Remember

I carry in my head the barest of etchings of a few trees:

An apple tree at the back of a yard, just beyond the fence

A walnut tree with a tire swing

A fig tree and my grandfather’s hands peeling a soft fig with a pocket knife

I cannot picture any of these. I only know them by these sparse labels, these objective descriptors, which may or may not even be correct.

As an adult, my touchstone tree is a different kind of tree entirely. There is more than one, maybe three trees, all a bit fantastical, each imbued with whimsy in its own way, each deciduous.

In winter, these trees give up their leaves and reveal their network of limbs.

Hug a Tree

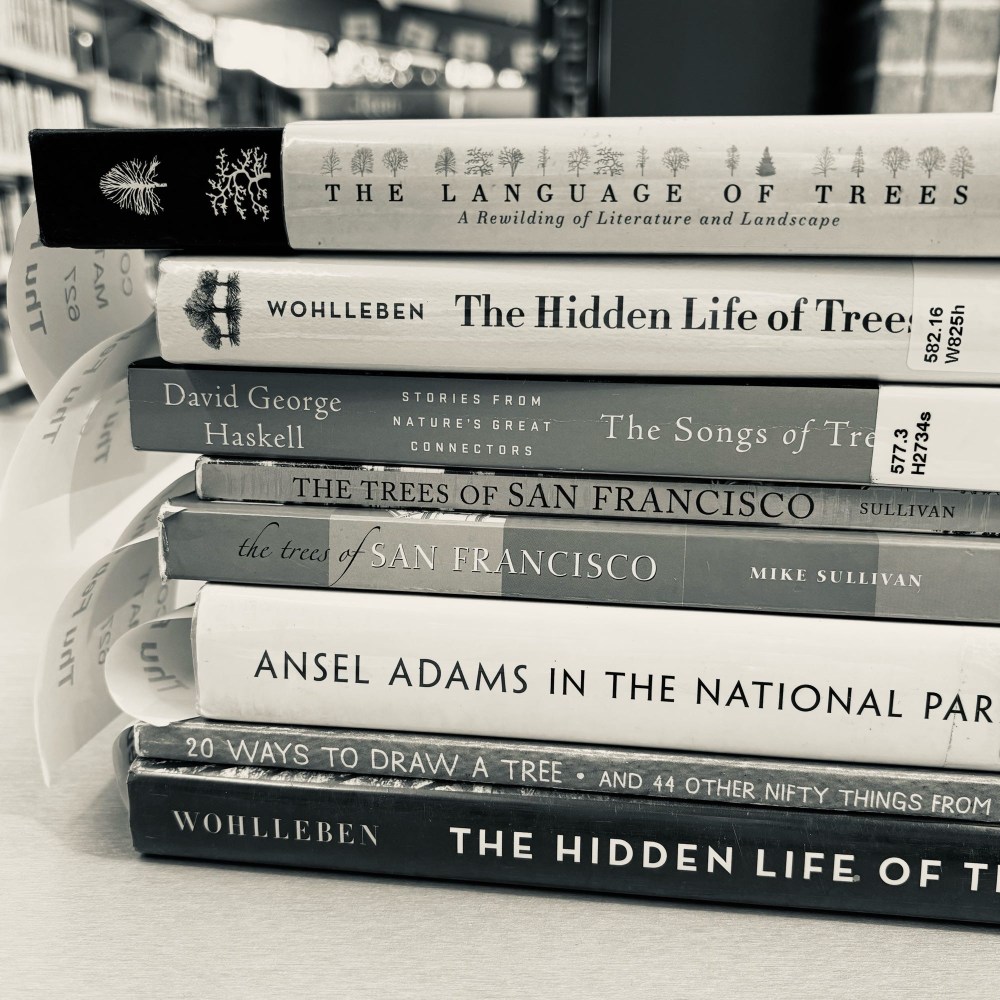

There are many, many books about trees. Looking at some of these (pictured) reminded me of once reading a profile of Edward O. Wilson as part of a science writing course. It was a beautiful piece about perspective and awareness, about our Goliath sensibilities, about the world that can be viewed when you sit down, carefully lift a log, and peer into the dirt.

I am not one to hug a tree. My most vivid memory of a tree in the last decade is at a disc golf course in a small city park in the South. As we neared the tree, there were zillions of the largest black ants I had ever seen swarming in rivers up and down the trunk.

I would be hard-pressed to hug a tree, but in the serendipitous way that things sometimes happen, maybe a day after I started thinking about trees for this prompt, I saw a Bluesky post in which someone was advocating exactly that—turn off the news, go out and hug a tree, and share a photo. There were lots of photos of people hugging a favorite or nearby tree.

At my local disc golf course, the remains of this massive tree have become home to a new ecosystem of plants. A. Cowen 2024

I don’t know where you fall on the side of hugging trees, but I hope trees, in general, inspire something in you. Winter trees give us the opportunity to see and appreciate the structure and the roots and the network of limbs without all the bravado or lace or whimsy of a canopy. You can see the way branches rise and cross and twist. You can see the way a tree bends.

Winter trees have nowhere to hide. They make no pretense. They reach upward, and they wait. They are graceful with their gnarled and lined limbs. This is the beauty of resilience and of quiet.

When I am among the trees,

especially the willows and the honey locust,

equally the beech, the oaks and the pines,

they give off such hints of gladness.

I would almost say that they save me, and daily.

— Mary Oliver, “When I am Among the Trees” (Devotions)

Send a Tree

This month, share a tree on your postcard. It could be a tree of memory, a favorite tree that was at a house you recall as a child, or somewhere you visited, or somewhere you lived. It could be a tree that you see outside your window right now or that you pass on the way to the bus or when you’re driving around your town.

Most of the bare trees I see are ornamental trees that punctuate sidewalks. They are small and compact. You may have large and stately trees near you that cast long shadows in the winter light. Your camera roll may hold many tree photos, full, flowering trees, but look for the winter trees.

This month, share a tree. Draw a tree. Collage a tree. Make a stained glass of the open spaces. Send a quote about a tree. Mail a tree.

In other months, the trees we choose might look different. But in February, there is still an invitation to look closely and to celebrate the form of a tree. Look at the spindly trees around you. Look at their shape, the branches the wireframe to something we simply think of as tree.

Look closely and capture the branches, trace their contours.

This is an exercise in negative space as well as in capturing form. What happens if you draw the spaces you see between branches and don’t worry at all about the individual limbs and leaves and how they rise into the air?

Tip! If you have a love of puzzles, you might check out The Language of Trees: A Rewilding of Literature and Landscape by Katie Holten. The book contains essays from more than sixty authors but also contains writing and illustration using Holten’s “Tree” font, a tree-based typeface. If you’ve ever done a cryptogram, you’ll find the examples of texts written in Tree enchanting.

In her afterword, Holten writes:

“This book is a love letter to our vanishing world, written with Trees.”

“I created a Tree Alphabet—a new ABC—by taking each of the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet and creating a corresponding tree drawing. These new ‘characters’ were converted into a font: a typeface that I called Trees. This font, the first of several, lets us type with Trees, translating our letters into trees, words into woods and stories into forests.“

“Translation is perhaps the most intimate form of reading. When we translate our words into glyphs, such as trees, it forces us to re-read everything. The Tree Alphabet forces us to revisit the past, re-present the present, and reimagine the future by translating or re-writing what we think we already know.”

The Language of Trees: A Rewilding of Literature and Landscape by Katie Holten

There are numerous books about the language and lives of trees. See also The Song of Trees: Stories from Nature’s Great Connectors by David George Haskell (author of The Forest Unseen) and The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate by Peter Wohlleben.

For those practicing and building a visual vocabulary, you might draw inspiration from 20 Ways to Draw a Tree and 44 Other Nifty Things from Nature by Eloise Renouf. It includes simplified trees and winter trees. My suggestion is to simplify your own!

Can you draw a tree wrong? No.

(Well, not if you have the “intent of tree” behind you. Ask a five-year-old. Look at Dr. Seuss’s trees. Be minimalist or be a realist or be something in between.)

A Year of Postcard Connections

This is the fifth in a year-long series of monthly postcard art prompts, prompts that nudge you to write or make art on a postcard and send it out into the world, to connect with someone using a simple rectangle of paper that is let loose in the mail system. You can start this month! Feel free to jump in and make and send your own postcard art.

Amy Cowen is a San Francisco-based writer. A version of this was originally posted on her Substack, Illustrated Life, where she writes about illustrated journals, diary comics/graphic novels, memory, gratitude, loss, and the balancing force of creative habit.

Images courtesy of the author.

These books are sentimental, but I didn’t recall who they were from or the year. In guessing, I was wrong about both time and origin. I pulled both books from the shelf, in writing this, and found handwritten notes on the inside covers, both from teachers who meant the world to me. Ironically, the one volume was specifically given to me because of the Ella Wheeler Wilcox poem. ↩︎

The post Connecting Dots: Send a Tree appeared first on PRINT Magazine.