As typefaces go, Atkinson Hyperlegible breaks the rules. But, in doing so, it’s paved the path for greater accessibility for people who live with low vision. To say that the original version of Atkinson Hyperlegible (released in 2019) found its audience is a vast understatement. The typeface, available on Google Fonts, graces 12,000 websites, has been downloaded over 150,000 times from the Braille Institute’s website, and is now available for use on Canva. The typeface is also part of the permanent collection at the Smithsonian.

Applied Design and the Braille Institute have launched an expanded version of their ground-breaking typeface, aptly named Atkinson Hyperlegible Next. The launch on February 10 coincides with low visibility awareness month (a stunning 285 million people live with vision impairment worldwide).

At the Braille Institute, we are deeply committed to breaking down barriers for individuals with low vision, and the success of Atkinson Hyperlegible has been a testament to the power of inclusive design.

Sandy Shin, vice president of marketing and communications at the Braille Institute

So what’s new with Atkinson Hyperlegible Next?

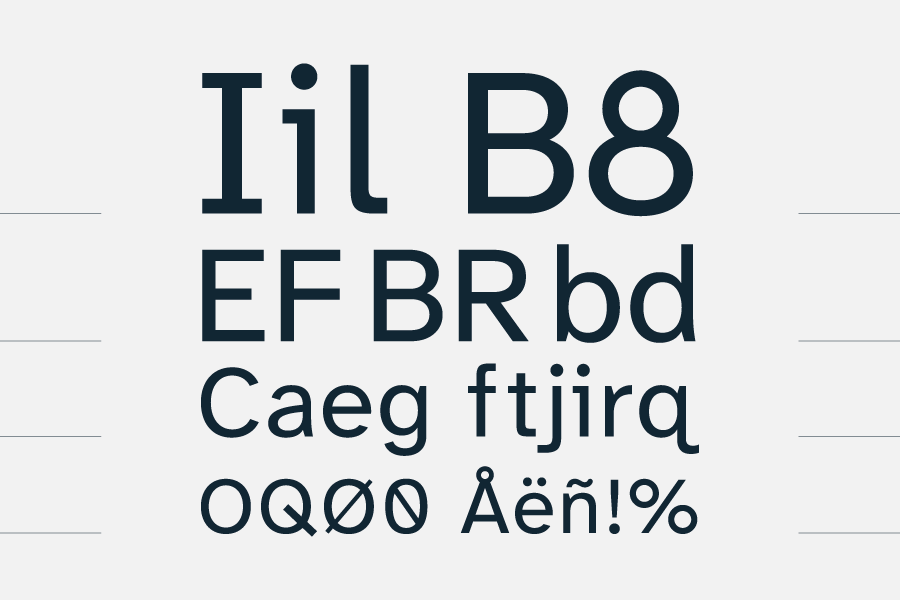

There are now seven weights (the original had two). Each weight offers new versatility as well, with an accompanying italic style. A new variable font format enables more dynamism and customization for digital projects. An expanded character set (4,464 per font) and language support (up to 150 languages from the original 27), give designers a lot more flexibility and range for a variety of uses.

A corresponding monospace typeface can be used in table-based and coding environments, allowing for easy scanning and the potential to open up new career paths for people living with low vision.

Variable (left); Monospaced (right)

Atkinson Hyperlegible Next is free for use, modification, and distribution. The expansion enables designers to help more people easily find and comprehend the information they need, in contexts such as outdoor and wayfinding signage, websites and apps, or printed materials.

Atkinson Hyperlegible Next represents a major leap forward in accessibility. By addressing the needs of a global audience while continuing to prioritize readability, this new iteration ensures that inclusivity and innovation remain at the heart of our mission.

Brad Scott, founder and principal of Applied Design

A few months ago, I spoke with Applied Design’s Brad Scott about the evolution of the collaboration with Braille on Atkinson Hyperlegible, the vision of the company he founded, and more. Our conversation is below, lightly edited for length and clarity.

It seems that a lot of the work you do at Applied Design is about helping people navigate physical and digital spaces. Was the whole idea of wayfinding and accessibility an intentional guiding force for Applied Design from the beginning, or was it something that grew organically?

Not to get too weird about it, but we put out into the universe what we wanted to do, and it’s kind of interesting how things coalesced. Craig Dobie is my co-founder (he is much smarter than me). Craig is from Scotland and he studied in Edinburgh. What’s interesting about his background is that he came of age in his early design career in London, and at that time if you wanted to design type, you designed type. Product designers designed products. Graphic designers designed communications. But design is design. It’s not so specialized. Design is anything that needs to be designed. This broader definition of what design is, is the mentality we brought to Applied Design. We weren’t thinking of graphic design, environmental graphic design, or industrial design. It’s interesting that you picked up on the fact that our work tends to transcend the design categories. It all comes back to this idea of giving access to people.

My background is in interior design. Though I never practiced as an interior designer, my program was very focused on Universal Design: the built-world answer to the ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act). The ADA was taking effect in the 90s. My professors were passionate about ADA, accessibility, and Universal Design, and by osmosis, I got interested in it as well. I went straight into digital design (web), and the reason I was hired was to apply those architectural principles to web and information design to make it more navigable. Back then, there was a lot of hierarchical information—more engineering-focused—and my job was to make the information more human. It came down to the idea of access. A lot of our projects at Applied Design manifest as accessibility, but at our core, what we’re really trying to provide is access, whether in print material, in the built world, or in industrial design. Giving people access to the things that they need at the time that they need them.

What are your thoughts on the debate around Universal Design? That nothing can truly be universal?

Universal Design is something that influenced me as an undergrad. It formed my worldview in a fundamental way. When we are working on something, we’re looking for the easiest way to give access to this type of information. Working with Braille, we found that a lot of the things that make something accessible to people with low vision, for example, will hinder someone else. There are always decisions that we have to make when we’re designing for a very specific group of people. The correct thing to do is to optimize it for them. As you gain more experience in your career, you realize all the decisions that you have to balance. The idea of focus becomes very important: What is the thing we want to improve and make more accessible for somebody? If you solve that problem, you might solve a broader problem for others. But, you also might create a hinderance for someone else. It’s not about getting stymied by it, but making sure you are thinking about it all the time.

If I were starting my career now, I would want to be universally accommodating, but there’s an impossibility to that. Atkinson was developed for people with low vision. That’s it. It’s gotten more popular in the marketplace because it solves broader problems than what it was designed for. For example, Jamie Oliver used it in his children’s book (a lot of the same characteristics of Atkinson help with dyslexia). It wasn’t designed for dyslexia, but when you start to look at it, solving for dyslexia intersects with a lot of the same principles.

Digging into the development of the original release of Atkinson, I learned so much about what kinds of things are confusing to the eye. When you design very specifically for something, I think what you create is an opportunity for people to get curious about why you made those decisions. It opens it up to a conversation.

You made my day with that statement. When we started working with Braille, we didn’t set out to create a font. The project was to refresh their corporate identity as they were coming up on their 100-year anniversary. When they first started advocating for Braille literacy, they had a lending library. Braille is incredibly expensive to print. The Bible took up a whole room! The institute is still heavily involved in the Braille community, but people with low vision started approaching them for services. Many of their strategies for helping vision-impaired people also worked for low vision. How do you cook? Set up a kitchen? Most of the people with low vision lost their vision at some point.; they were having to adapt to a new reality. So, our project was to help Braille develop a new identity that encompasses their full mission.

But, in doing that, you do your discovery and put concepts together. Craig, the project’s CD, and Elliott Scott, the lead designer, couldn’t find a font. Through our research, we learned about many kinds of low vision. Blurriness is one thing but diabetic retinopathy is another (if you see someone holding a book to the side, that’s often because something is in their field of vision, so they look kind of out of their periphery). Helvetica is beautiful and uniform, but you can’t tell the difference between an L and an I. Times New Roman wasn’t the feel we wanted. Comic Sans is an amazing font, actually. In schools, teachers use it and love it because it has a lot of letter differentiation, so new readers have an easier time distinguishing it and reading. But, that wasn’t quite right for our project either. So, Elliott started sketching an idea in Illustrator and presented it in the corporate identity. Braille responded with an idea: Create a font that we make available in the market.

The project was very much about generating awareness and starting a dialog. The first version of Atkinson Hyperlegible was released for use without restrictions and no licensing fee. This dialog is now more important than ever because as we’re living longer, more people are going to have vision-related issues. The typeface opened up the conversation so we could start increasing advocacy for low vision.

Learning is what this whole thing is about.

What were the most controversial design choices of the original typeface?

When we started to focus on how to design it, we wanted to create unambiguous letterforms without ending up with something that looked like a ransom note. We wanted it to look cool. We ended up intentionally breaking a lot of typography rules to increase legibility. There is a lot of intentional disharmony between the letterforms, not that they don’t go together.

There wasn’t any one controversial choice, but there were a lot of quirky little letters. The 8’s wider bottom (because we don’t want it to look like a B). Everyone busted on us for the stacked ‘g.’ The lowercase ‘i,’ also, because it’s very different. As was the slant on the zero oriented in the wrong direction. The controversy was more because the quirky letters were put together in a system.

If it breaks the rules, yet it solves the problem, can we actually call it breaking the rules?

We presented it at TDC. Did it break the rules, or did it create a new category of type? It goes back to the fact that it’s a dialogue that people weren’t having before.

Did this experience spark any other ideas or a dream project that Applied Design would like to tackle? What accessibility problem should designers focus on?

A million areas! Anytime you can reduce the stress in someone’s life, you should explore it. That’s our POV. We’ve been really lucky to have clients that want to do that. Strangely, even the packaging we do has some kind of accessibility thing to it. We always ask: Does this have to be a stress point for people?

We work a lot with the MTA. Take the turnstile. Most people go through without a hitch, but if one can’t go through, it makes you reconsider the turnstile. MTA does a really good job of asking questions. But, it all starts to spiral. Could we increase the legibility of the signage? How do we start inventing aural cues? How do we start looking at the textures on things to cue people? How do you concentrate on sightlines? Is it possible to make a fast lane and a slow lane?

The important this is to start asking questions and not hold things sacred. I say this to my son. The world is built. We built it. You can make anything. But just because it’s made doesn’t mean that it’s THE answer. Whatever it is was probably remarkable at the time it came out, but its environment and we’ve changed. Is it antiquated, or is it doing a perfect job and shouldn’t be touched? So often, we want to fix the things that really don’t need to be fixed. I’d answer your question like this: There are a million things we could make better, but it depends on where I’m sitting that day. The best thing is when a client comes to us and says, hey, we’ve noticed this. Then: How do we start to develop a better experience for people?

Read more about Atkinson Hyperlegible (and the update) on the Braille Institute’s website.

Read more about the Applied Design team for Atkinson Hyperlegible Next, including Elliott Scott (creative director) and Megan Eisworth (designer). The foundry Letters from Sweden also collaborated.

The post Atkinson Hyperlegible Next Expands on Low Vision Accessibility appeared first on PRINT Magazine.