When it comes to comic and illustration prowess, often the clichéd adage “less is more” can be applied. Distilling an object, animal, or character to its most basic form through shapes, colors, and lines is a finely honed skill that, when done by a master, can charm the masses. French illustrator Jochen Gerner is one such virtuoso, image-making all manner of characters with his trusty felt-tipped markers on lined notebook paper. Gerner has authored a handful of books featuring his vibrant style of carefully considered overlapping lines and colors, and his work has appeared in a number of French publications as well as the New York Times.

I am proudly in the category of those smitten with Gerner’s way of seeing the world. To learn more about how that point of view came to be and is executed, I reached out. His responses to my questions are below, lightly edited for length and clarity.

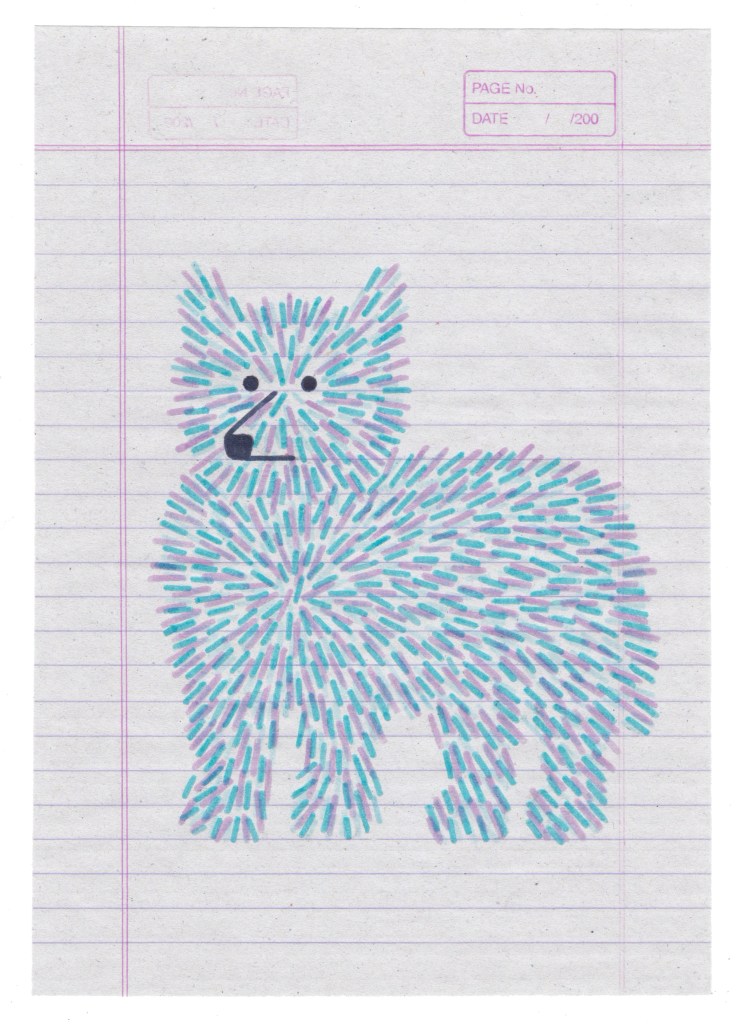

Credit: ©Jochen Gerner – éditions B42

Can you give some insight into your creative journey, and how that’s led you to where you are today?

I grew up in the east of France, accompanied in my artistic research by my father, a drawing and art history teacher, and by my mother, a lexicographer. I benefited from an environment made of many images and books. I was a student at the Nancy School of Art from 1988 to 1993, where I participated in graphic design, drawing, engraving, and screen printing workshops.

After that, I moved to Paris, and very quickly began to make many drawings for the press and for children’s publishing. Then I lived for a year in New York, where I was able to meet many artists—cartoonists, sculptors, painters—explore the contemporary art world, and meet art directors of the New Yorker and the New York Times.

Back in France, where I lived successively in Paris and Lille, I continued my work in publishing by making experimental comic book projects. Following this work, I was invited to exhibit in the Anne Barrault Gallery, a contemporary art gallery in Paris. Since 2004, I have been making many exhibition projects in partnership with the Anne Barrault Gallery and others, along with art centers and contemporary art museums. My book projects can become exhibition projects, and vice versa.

How did you develop your unique illustration style?

I believe that my graphic writing comes from both the codes of graphic design and the pictorial references of illustration and visual arts. I grew up with books. My relationship with the image is always done according to the criteria of print. I examine images to understand their narrative and technical principles.

Simplicity is complex and sometimes allows multiple readings.

I sometimes work by covering; I apply ink or paint to synthesize my drawing forms in a way that gets closer to a principle of the graphic alphabet. Simple and abstract forms associated with each other, construct figurative representations. But simplicity is complex and sometimes allows multiple readings.

What illustrators and artists have been most inspiring to you in your own practice? What other influences have helped shape you and your artist point of view?

During my childhood and apprenticeship, I was heavily influenced by my father’s vision and drawings. He was very critical and always had a very fair opinion. His own graphic writing was close to contemporaries like Saul Steinberg or Tomi Ungerer. I still appreciate many cartoonists from that period, but I am more influenced today by artists who work in fields far removed from drawing, press cartoons, or publishing.

I am very sensitive to the work of certain artists like Ellsworth Kelly, and On Kawara, and more generally to contemporary art. I am also interested in architecture, typography, archaeology, forms of contemporary literature, and even botany.

What is it about birds and dogs that you find particularly compelling to draw?

The idea of making a series of bird drawings came through color: it was about experimenting with the infinite compositions and superpositions of colored lines. Since my childhood, I have always drawn birds: two lines for the beak, two lines for the legs, and in the middle of the body, then the tail and wings can be placed in a certain disorder.

Credit: ©Jochen Gerner – éditions B42

Dogs stood out to me for their sculptural and abstract character. Any mass of hair with a nose, and possibly two points for the eyes could be similar to a dog. It was, therefore, more a question of working on silhouettes and textures.

These two types of animals made it possible to build a series and, therefore, to work on a principle of variation. Through their shapes or colors, they are also very graphic animals.

What’s your typical process like for drawing a dog?

Drawing a dog is a bit like drawing a piece of clothing, a mossy texture, or a furry shape. Any abstract shape composed of a principle of lines can lead to the representation of a dog. It is one of the only animal species with so many variations of breeds, with such specific defining characteristics and gaits. It’s a very rich field of experimentation and discovery for a drawer.

Sometimes I discover a new dog and draw it immediately. Other times, I invent a shape that will lead me to an imaginary dog. Today, I don’t necessarily know which dogs are real or imaginary among all of those I have drawn.

What are your main tools for your practice? What sorts of pens, markers, pencils, paper, etc. do you use?

For my series of color drawings, I use felt-tip pens with pigmented Indian ink (Faber-Castell Pitt Artist Pen brush). For other drawings, often done with black lines, my favorite tool is a brush dipped in black Indian ink (Talens Indian ink).

Credit: ©Jochen Gerner – éditions B42

Making simple and direct drawings of animals, in black or very colorful lines, without narrative captions, seems to me perhaps to participate in a universal understanding.

Why do you think your illustrations have resonated so strongly with the masses?

Making simple and direct drawings of animals, in black or very colorful lines, without narrative captions, seems to me perhaps to participate in a universal understanding. But this is only part of my work. Many other drawings are more complex and more experimental in their forms and, therefore probably more confidential. I like to work both for different audiences, for printed editions, or for wall exhibitions.

The post Jochen Gerner Uses Whimsical Simplicity to Bring his Animal Illustrations to Life appeared first on PRINT Magazine.