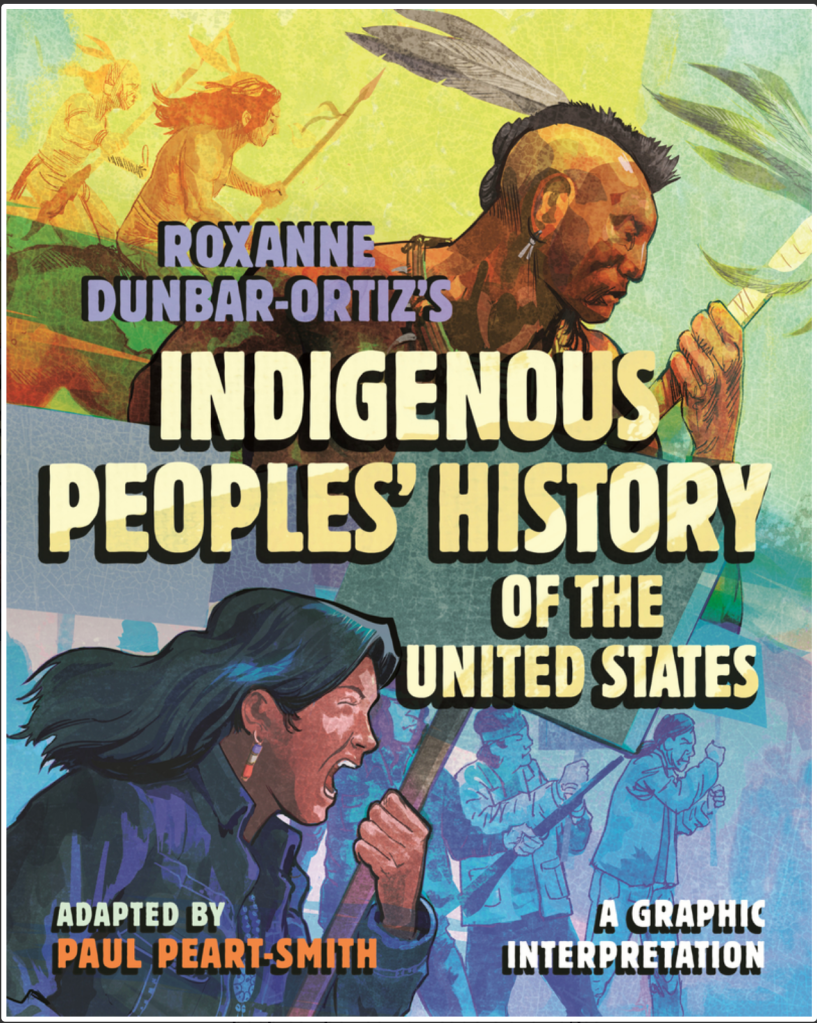

Learning from the past is essential to shaping a more equitable future and advancing society with purpose and clarity. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s critical book An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States is brought to life in a new way, now transformed into a powerful graphic novel. Illustrated by renowned cartoonist Paul Peart-Smith, this adaptation not only makes the history accessible but also vividly captures the brutal realities of settler-colonialism and the enduring resilience of Indigenous peoples across four centuries.

Known for his graphic adaptation of W. E. B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk, Peart-Smith, working with seasoned graphic novel editor Paul Buhle, brings a visual depth to the narrative that makes this history both accessible and compelling. Through full-color artwork, complex histories are distilled into powerful, accessible imagery that invites readers of all ages to reconsider the past through the lens of those who lived through it.

The medium of comics and graphic novels creates visual opportunities for complex ideas. … I believe this is a powerful way to engage with young adults, whose worlds are shaped by visuals like never before.

In an age when visual media dominates how we process information, this graphic adaptation is an essential tool for connecting with new generations. It rekindles a crucial dialogue about what we choose to remember — and, just as importantly, what we choose to forget — acting as a bold reminder of the stories often omitted from mainstream narratives, shining a light on the centuries-long efforts to erase Indigenous identities and the equally enduring spirit of resistance.

Whether you’re a student, a historian, or simply curious about the often-overlooked truths of America’s past, this adaptation promises to be as enlightening as it is visually stunning. I found myself immersed not just in the visuals but in the urgency of its message: understanding the past is the first step toward justice. And if that journey begins with a graphic novel, then it’s a journey well worth taking.

I had the opportunity to ask Paul further questions about this important adaptation. Our conversation is below, lightly edited for length and clarity.

What unique challenges did you face in visually interpreting the complex and often harrowing history of Indigenous peoples in the United States, and how did you balance historical accuracy with the artistic storytelling in your illustrations?

I had an idea of the scale of the task, but I’m relatively new to adapting, having done only one prior historical book, so I walked into this project with a little bit of a beginner’s arrogance, or better put, naivety. One of the challenges I faced was the broad scope of the story which covers many years, indeed centuries of events. I had to define a pathway through the historical record to help me choose what I could fit into the book. There was so much I could have used, but in the end, I had to make it my interpretation of Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s great original work.

Given the emotional weight and significance of this history, how did you approach capturing the resilience and perseverance of Indigenous communities over four centuries?

Thank you for the question. This leads me to another challenge of the book: how to show the often violent Indigenous resistance to violent occupation and colonisation, without mythologising violence itself. Comics and graphic novels are known for their use of action to entertain, but this wasn’t that kind of book. I wanted the brutality to land hard, not to be brushed over. Having said that, I had to make sure that the book wasn’t just a tale of Indigenous woe either. There were victories, as well as massive losses. We cover how the population survived, adapted to, and sometimes assimilated within settlers’ culture. We share some of the great speeches made by Indigenous leaders of the past and present, speeches that described and rebuked, the day-to-day reality of exposure to settler influence.

How did your experience with adapting The Souls of Black Folk inform your approach to this graphic adaptation, and what did you find distinct about translating An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States into a visual medium?

Well, there were differences and similarities between the two projects. With The Souls of Black Folk, each chapter of the original book written by W.E.B. DuBois was a series of essays collected into one volume. Because of that, I got the opportunity to work in a different style per chapter to separate each essay. In An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, each chapter had a theme, but it was a rolling history so I chose to use different styles throughout the book, unrestricted by chapter. The only rule that I set myself was that I could use whatever means I could to explain the theme to the reader. In practice that meant that some pages required panel-to-panel storytelling that read like a traditional comic, and other pages were illustrations or even infographics, whatever visual tool worked best.

What role do you believe graphic adaptations, such as this one, play in making critical histories more accessible to wider audiences, especially younger readers?

I hope that they play a major role! The medium of comics and graphic novels creates visual opportunities for complex ideas. We’ve always accepted that in newspaper cartoons, and this historical work builds upon their example. So for adults, there should be no stigma attached to this medium. I believe this is a powerful way to engage with young adults, whose worlds are shaped by visuals like never before. Comics are a quieter medium than TV, video games, and social media, but they “shout” louder than prose from the bookshelves, and lend themselves quite well to video advertising and reviews. I’ve been very pleased with the feedback I’ve seen from YouTube reviewers for example.

Your illustrations are described as evocative and integral to sparking crucial conversations. Were there particular moments or themes in the book that felt especially important or challenging to depict visually?

There were two passages in the original book that I found challenging to depict. The first was showing on the original tribal map of America the trade routes that were cut off by colonizing troops. I wanted to get across the scale of the operation which forced starvation and social breakdown of the indigenous population. I had the map on the first tier of the page and a visualisation of the consequences of the blockades on the people themselves. I wasn’t sure that I had gotten the concept across, and I tried various graphic icons to depict the trade routes, soldiers and tribes. In the end, I went for clarity over “cleverness”, showing the different tribes and reusing the same soldier icon for consistency and to suggest the relentless nature of the colonists.

The second passage covered the era of self-determination away from the former Western colonies which became more prevalent in the latter half of the 20th century. I wanted to broaden the scope by using examples from other countries who had freed themselves of colonial powers and, in some cases, risked the brunt of colonial backlash. I hinted at this by using the example of Patrice Lumumba, the first independent leader of Congo. If readers are interested further, they can read his story outside the book; it’s well worth the trouble. This global trend swept up and gave great encouragement to Indigenous leaders in America to push for their own self-governance within the United States. It’s difficult to illustrate such big ideas. I gave it my best shot.

We’re super lucky to have Paul involved with the 2025 PRINT Awards. He’s one of the jury members for the Hand Lettering, Illustration, Graphic Novels, and Invitations category. The next PRINT Awards deadline is January 21st!! Learn more about submitting your work here.

The post Paul Peart-Smith Makes ‘An Indigenous Peoples’ History’ Accessible in Graphic Form appeared first on PRINT Magazine.