There is some controversy surrounding pink. The first sentence of the latest volume in Michel Pastoureau’s History of Color series titled Pink, asks: “Is pink a color in its own right?” It goes on to note, “There are grounds for doubting this or at least asking the question.” Scientifically speaking, it is “neither color in terms of material nor light, but simply a shade of red, absent from the color spectrum.” Tell that to the Pink Panther, which Pastoureau, a historian and authority on color, states has “done more for the glory of pink than all the merchandising for little girls of eccentricities of pop art.”

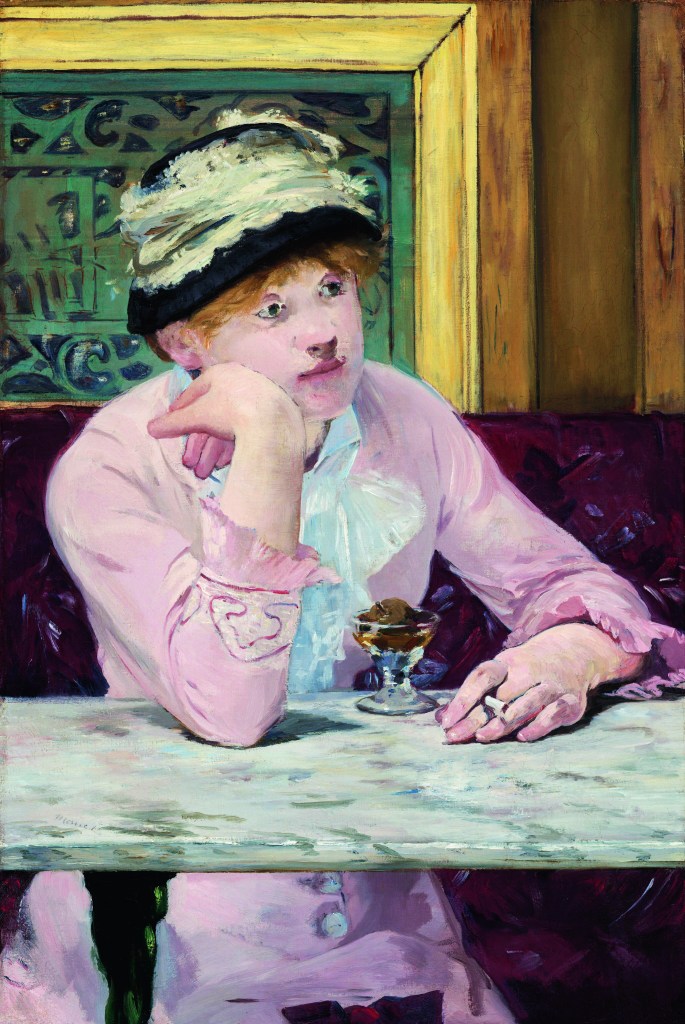

Édouard Manet, La Prune, 1877 ou 1878. Washington, National Gallery of Art. © Bridgeman Images.

This book is a testament to the micro details of art and science, function and aesthetics melding together. Pastoureau’s text is spirited and filled with ideas. “The history of pink,” he writes, “is an uncertain and tumultuous one, difficult to trace because for so long this color seemed elusive, fragile, ephemeral, and as resistant to analysis as to synthesis.” Being the latest volume in his investigations into the colors blue, green, black, yellow and white, his “plan” is to go chronological. He looks at color not only in artistic terms but from scientific, social and religious values.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Charles Claude de Flahaut, Comte d’Angiviller, 1763, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Pink was not always called “pink.” From the 16th through the 18th centuries, many names were ascribed to the hue. For instance, “the adjective roseus sometimes describes beautiful female skin,” he writes, “pleasing to look at or touch, but its value is more affective than chromatic.”

Pink ribbons also had a special meaning during this time. A pink ribbon is the most prized possession of an unrequited lover who dies by suicide and leaves a note to be buried with it on his person. Likewise, Jean-Jacques Rousseau writes how pink, because of its paleness, is a truer symbol of love than “excessive artificial red.”

Henry William Bunbury, The First Interview of Werther and Charlott, 1782.

Pink provided a “newfound joie de vivre” in clothing after the dark years of the Plague. However, as Pastoureau explains, the color actually preceded that pandemic, so “it is not clear that this color was considered particularly cheerful or comforting at the time.” Yet whatever its ultimate symbolism, pink was admired and remained so.

And yet, pink also signified femininity as well as identity. The infamous inverted pink triangle used by the Nazis to brand those in concentration camps gave a dark significance to the faded rose color.

Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo, Saint Matthew and the Angel, 1534. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Pastoureau concludes his study with a view toward popular culture and fashion. He reproduces the famous photograph of a smiling President John F. Kennedy beside Jackie Kennedy at the Dallas airport only moments before his assassination. Jackie was wearing the pink Chanel suit that became iconic as blood-splattered evidence of the death of Camelot.

I was unaware of Pastoureau’s books and his passion for mixing color history, anthropology and sociology. What makes color is not only eye-brain mechanisms—”It is society,” he concludes, “with its definitions, classifications, laws and practices, often different from those of science.” After reading Pink: The History of a Color, I will never look at swatches the same way.

Le Roman de la Rose, Paris, vers. 1345-1350. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, ms. Français 1567, folio 7.

Stefano di Giovanni dit Sassetta, The Journey of the Magi, Sienne, ca. 1433-1435. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Boccace, Des cas des nobles femmes, vers. 1510. Genève, Bibliothèque municipale, ms fr.190/2, folio 30 verso.

;

The post The Daily Heller: How Did Pink Become a Color? appeared first on PRINT Magazine.