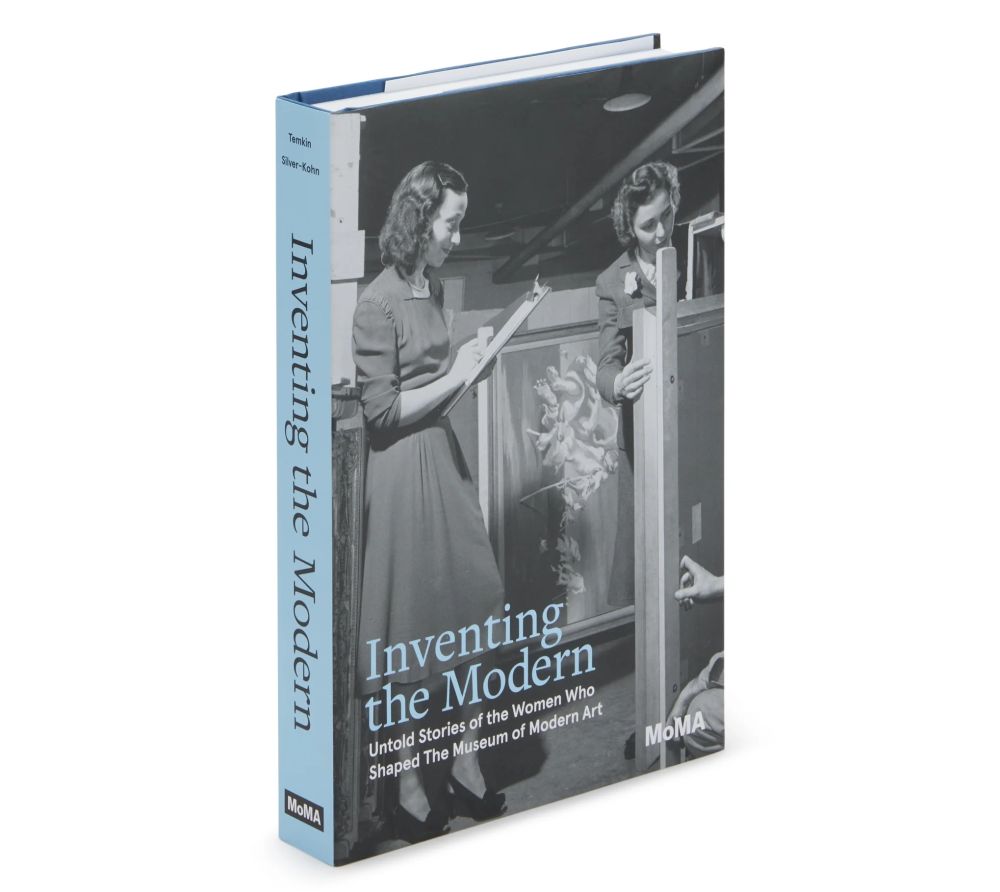

The Museum of Modern Art in New York City, which opened in 1929, has never appointed a woman as director—although its three founders were women. The names Lillie P. Bliss, Mary Quinn Sullivan and Abby Aldridge Rockefeller (whose townhouse on the top floor was used as the first gallery) may be known to some museum-goers from the credits on wall labels for masterworks throughout MoMA’s galleries. However, despite enjoying foundational status, their names remain largely unknown. As Anna Deavere Smith writes in the foreword to Inventing the Modern: Untold Stories of the Women Who Shaped The Museum of Modern Art, these founders and 11 others featured in the book “played a role in transforming the museum from a fledgling operation into the institution we know today.”

Edited by Ann Tempkin and Romy Silver-Kohn, this splendid new book of biographical essays by women about women who “shaped MoMA’s early years, as founders, patrons, curators and directors of various departments” is indeed revealing. From the outset these early to mid-20th-century trained scholars and fervent collectors were pioneers of “uncharted territory,” which was a curious blessing. “This left the door open for a host of women to essentially make things up as they went along,” Tempkin and Silver-Kohn write in their enlightening introduction. They introduced many firsts—art restoration; circulating exhibitions; gallery design; marketing, publicity, advertising and graphic design departments, and even the registrar—that were essential to MoMA’s success.

Alfred H. Barr Jr. was the museum’s founding director, but his wife Margaret Scolari Barr’s championship of modern art and friendships with key artists made her “an essential partner in the achievement and legacy of Alfred Barr,” former MoMA Director Richard E. Oldenburg is quoted as saying. (She was also a respected art historian and author in her own right.) The fascinating essay devoted to “Marga,” as she was known, was the first time I had ever heard or read her name, yet I soon realized how integral her work was to accomplishing her husband’s vision and legacy of integrating fine and applied arts under MoMA’s wide umbrella.

Other than Abby Aldridge Rockefeller, whose pursuit of the Modern was way ahead of its time, only one other name was familiar to me: that of Elodie Courter. I personally knew her only by her maiden name, Elodie Osborn, the wife of Robert Osborn, the expressionistic illustrator, author and political cartoonist who I wrote about numerous times and befriended as a neighbor in the Berkshires. Elodie was a lovely, gracious person. She left her post to devote time to her two small boys. Little did I know that she had a huge role—if sometimes an under-appreciated one—in MoMA’s outreach “mission” and overall history as the first director of circulating exhibitions. She literally wrote the book (and accompanying exhibition manuals) on how to care for, ship and manage traveling modern art to all corners of the United States. Today the field that Courter-Osborn built is a major asset in MoMA’s vast portfolio and “her influence on educating the American public on the subject of modern art cannot be overstated,” writes Silver-Kohn. I often wondered why Bob and Elodie’s Modernist home designed by Edward Larabee Barnes reminded me of a MoMA gallery. Now I know.

Inventing the Modern is brimming with surprising biographies of women who either could predict and promote the future of art or put intricate documentation systems in place to ensure its existence. Yet there is no more fascinating individual from my perspective than Ernestine Fantl Carter, whose five-year mid- to late-1930s tenure at MoMA was marked by landmark accomplishments, especially in terms of industrial, architectural and graphic design. She was Barr’s top student at Wellesley College and was hired by him to be Philip Johnson’s curatorial assistant in the Department of Architecture and Industrial Design. Within a year she had taken over the Department of Publications. After Johnson left (owing to his participation with the Nazis), Fantl was made the first and only woman head of a department. She was curator of historic exhibits, including Machine Art, Cubism and Abstract Art, Posters by Cassandre and Modern Architecture in England. She was promoted to full curator at half of Johnson’s salary. In 1937 she married an antiquarian book dealer, moved to England, joined the Ministry of Information, curated exhibitions and edited a book on the fashion and war photographer Lee Miller. After the war she was appointed fashion editor of Harper’s Bazaar and columnist at The Observer, wrote a book, With Tongue in Chic, and ended her journalism career as a ranking editor of the London Sunday Times. However, until reading Inventing the Modern, I’d never heard of her—and I have most of her catalogs.

Learning about the erased is the value and joy of this volume. The only regret I have is that one significant curator of Midcentury graphic design at MoMA, Mildred (Connie) Constantine, is missing. She was a pioneer by any of the standards measured in Ann Tempkin and Romy Silver-Kohn’s decidedly superb book.

(Header photograph: Elodie Courter c. 1945. Museum of Modern Art Archives.)

The post The Daily Heller: The Women Who Made MoMA Modern appeared first on PRINT Magazine.