American graphic design is rooted in the histories of printing, which owe a lot to advertising. When the making and selling of goods became an industry in the mid-19th century, the need to inform consumers prompted unique techniques. Packaging, posters, periodicals, trade cards, handbills and countless novelties were produced in varying graphic styles to capture the eye and foment desire. Graphic design grew out of this creative yet pragmatic need to appeal to customers.

By the late 19th century, the look of the product that printers made was just as important as the products they contained or disseminated. Styles expanded the reach of advertising. And ever since, practitioners have laid foundations for histories of illustration, typefaces, typography and layout—as well as chronicling how design worked or failed to ignite interest in products, institutions or ideas.

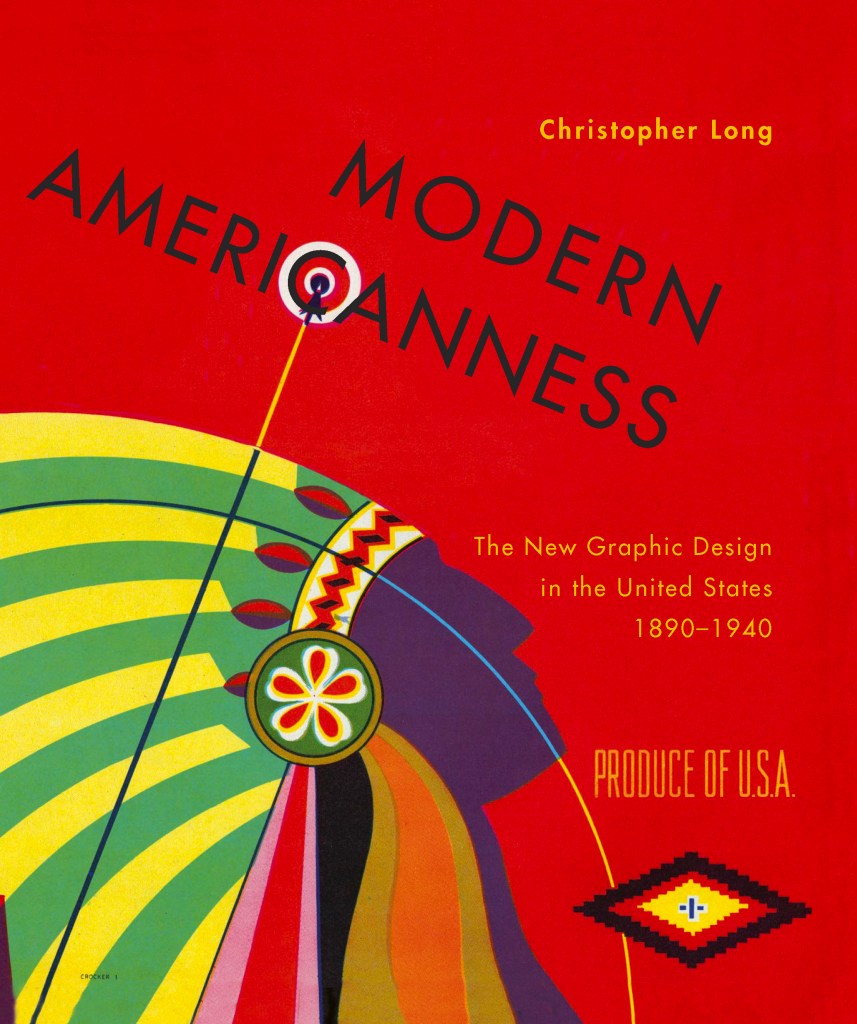

Christopher Long is a design scholar and author whose previous book documented Lucian Bernhard, the inventor of the Object Poster (considered by some to be the first simplified modern approach to advertising and graphic design). His latest is Modern Americanness: The New Graphic Design in the United States 1890–1940, a rigorous and successful effort to unpack the Modernist language as a combination of European and domestic art idioms.

Where these American roots and routes come and go is the topic of our conversation below. Long’s research led him down some untraveled roads, and he found some fascinating historical cul-de-sacs. His work, so far, has made more than a dent in an old canon of curious assumptions.

Your earlier book was about Lucian Bernhard, the master of object posters. Why did you select the birth of American modern design for your second? Did it have anything to do with Bernhard coming to America in the 1920s and bringing his economic style with him?

I actually started with the second book, the one on modern American design. At first, my intention was merely to write an essay about the impact of streamlining on American graphic design. The more I researched the topic, however, the more I found there was a larger story that hadn’t been told, at least not fully: the beginnings of the new graphic art in the United States. It was while I was researching American design of the 1930s that I became interested in Bernhard. He had moved to the United States permanently at the end of the ’20s, and his work for companies like Amoco and Rem was cutting-edge in the American context of the early 1930s. I started to read the literature on Bernhard and quickly became aware that the stories he told about his life and work (including the genesis of the famous Priester poster) simply did not add up. I became obsessed with getting at his real story. I put the American design book aside (by then, I had written the first three chapters), and for the next two years I worked on the Bernhard book. After it was published last year, I came back to the American book.

Bernhard was a “Modern” but not a “Modernist,” which is a rubric reserved for the early 20th-century European avant-garde. How do you define “modern”?

We can understand the term modern in two ways: as a style (and related movement) or as an expression of the new industrial age and all that went with it. In my book, I write about both types of “modern”— the purified form-language (which emerged in Europe and, later, in the United States) we now associate with the avant-garde, and a novel way of communicating on a two-dimensional surface with simple direct forms. The American story before 1940 is more about the latter than the former. It is about how the advertising field was embracing more straightforward forms of visual communication to sell things. To make that distinction even clearer, I used the term modernness, implying that the book is about everything that went into this new mode of graphic design. It is not only about how things are arranged on the page, but also how messages are being conceived and transmitted. A good example of this is the “soft sell,” the notion of creating in the mind of consumers certain qualities associated with a brand—luxury, for example. One of my favorite examples in the book is the Arrow Collar ad campaign, which is predicated on messages about manliness and upward mobility. These new ways of expressing “value” were inherently modern, but they are not necessarily Modern in a stylistic sense. They are the artifacts of an American society and culture that was rapidly transforming, embracing novel ways of living, working and spending leisure time. The point of the book is to demonstrate that all this was going on in the United States in a way that was different from Europe.

We both agree that Earnest Elmo Calkins was a Midwestern conservative who imported “modernity” to American advertising. Was Calkins, who wrote for the “modernistic” advertising journals, America’s first “Modernist”?

Calkins is a fascinating character. A deaf man who started his career as a printer, Calkins moved to New York when he was in his 20s and found employment with Charles Austin Bates. Bates had one of the first “full-service” advertising agencies, meaning he wasn’t merely a broker but also assisted clients to devise their advertising campaigns. Calkins and another employee, Ralph Holden, left Bates’s employ to start their own agency. Both men had come to believe that print advertising should essentially be visual (up to that time, written “copy” had dominated American advertising). Calkins also thought that advertising should reflect the current state of art. He took what most saw as a radical step: He began hiring artists to create his company’s ads. Calkins did not set out to be a “Modernist”; it just seemed logical to him that images, especially arresting images, could be a potent sales vehicle. And simple images performed that job better than traditional ones. Calkins was a pragmatist: He recognized that the new art trends were visually “affecting,” but also that they reflected American reality. As you note, he was also a prolific writer, and he was especially good at discerning new trends in art and design.

The Art Deco era (known as “moderne”) was a strong wave that hit the USA. Is that what passes for the early advent of modern in America?

I think for many people it is. At least, it is an obvious transition that seems to signal the shift to a new modernity in design. But I believe that the new graphic design in the United States has its origins some 30 years earlier, in the 1890s, when a handful of designers began to adopt the idea that simplicity was the key to articulating modern life. Edward Penfield’s early posters for Harper’s, for example, show modern people going about their everyday lives in ways that would have been unthinkable just a few years before. It isn’t just the form that is new in his work; it is also the content. Penfield’s often droll depictions are infused with a marked forthrightness, but, even more, they are expressions of an altered way of seeing the world.

Your book rings all the right bells regarding how to define a style that washed over consumables, architecture, fashion, etc. What do you feel you missed in telling this story?

I made a conscious decision at the outset not to write about two important aspects of the story. One is the birth of modern typography. Although I allude to it here and there in my text, I don’t engage it directly. It is not that I don’t deem it important—quite the opposite. It is a tale that needs to be told in another book; it is simply too large to fit into what I wanted to say about the rise of the new advertising art. I also deliberately excluded modern American package design for the same reason. It, too, is deserving of a book of its own.

Whereas European Modernism was never fully embraced in the U.S., streamlining (which was ostensibly industrial and product design) was America’s Modern movement. How was that represented in terms of graphic design?

It is interesting that you ask that question. It is exactly where I started with this book. As I tell in the introduction, I happened to go into Michael Maslan’s poster and ephemera shop in downtown Seattle a few years before the COVID-19 pandemic. While looking through a folder titled “Art Deco,” I saw numerous examples of streamlining. Their quality surprised me. I hadn’t associated that degree of sophistication with American design from those years. I bought about 20 pieces, thinking that I would write an article about how streamlining was American’s great contribution to the new design. Over time, however, I changed my view. For one, there was evidence of streamlined forms in European, especially British, design, though it was not as pronounced as it was in the United States. But what I came to see was that “graphic” streamlining was really about something else: the depiction of motion. And here, the Americans were quite innovative and sophisticated. What was meant to be an article is now a chapter in my book. It is about how motion—and speed—became a shorthand for modernity in the American context.

What did you learn from your research that alters or challenges existing notions and scholarship about American design?

If you read most surveys of the history of modern graphic design, they give very short shrift to American design before 1936 or so. Modern American design in most of these accounts begins with Lester Beall and Paul Rand. There is also a tacit assumption in almost all these accounts that Modernism was imported—that it came from Europe with the arrival of figures like Herbert Bayer and Ladislav Sutnar. I wanted to demonstrate that there was an indigenous American Modernism, different from what had developed in Europe, but also powerful and, at times, of high quality. I also wanted to discern what was truly American and what was borrowed from Europe. That turned out to be far more challenging than I had assumed when I started the project. But after several years of digging, I found many examples of good design. Anyone flipping through this book will see that the very best of American design in the four-and-a-half decades before Beall made his great breakthrough with the Rural Electrification Administration posters was both inspired and affecting. That is not to say that good design in the United States was universal: The mainstream of American advertising was often lackluster. But the crème of designers (most of them working in New York, Chicago, Detroit, San Francisco or Los Angeles) was both innovative and supremely skilled.

This project had a steep learning curve for me. I had a great deal of help along the way from Mark Resnick, who, with his wife Maura, has what is certainly the largest collection of American posters anywhere. He pointed me in the direction of makers and movements about which I knew little, if anything at all. This was hugely important because I found that the institutional collections—museums, libraries and archives—often didn’t have the sort of material I was interested in, for much of it is ephemera. I turned to another source, one I never thought I would use as a serious researcher: eBay. I began searching the site year by year for the 50 years from 1890–1940. What I found (and purchased) makes up almost a third of the images in the book.

The post The Daily Heller: What is Real American Modern? appeared first on PRINT Magazine.