This post originally ran on April 11, 2022.

Last week I received an email that has haunted me for reasons that will become clear. The missive explained that a passerby stumbled upon a pile of trash on 100th Street and Central Park West in New York City, including garbage bags containing numerous large ring binder portfolio books filled with original cartoons and illustrations. The passerby grabbed as many as possible and lugged them home to share with his wife. By coincidence she happens to be friends with an artist pal of mine, to whom she sent an email in hopes of learning something about the creator of the discarded art work. Included in the email were photos of the artwork, each signed with a name. My friend had no idea who the creator was, so she forwarded the photos to a friend of hers, a cartoonist, who is also a friend of mine. He did not recognize the artist either. So he decides to send the correspondence to me on the off chance I might know the artist, “because,” he wrote in his email, “you know everyone.” This is a flattering exaggeration, but … it turns out I do indeed know the artist, whose name is Bill Lee.

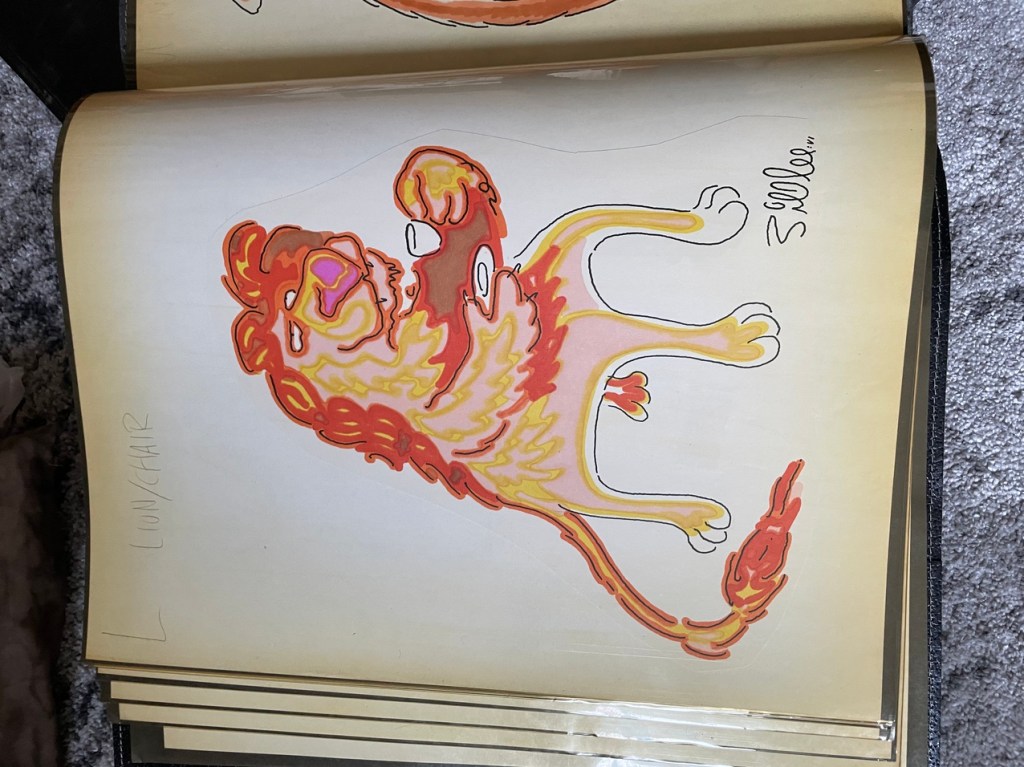

Not only did I know Bill Lee, but for many years we had a close working relationship and deep friendship. Bill was one of a new breed of satiric gag cartoonists. He had a singularly fluid linear style. He was also the humor editor of Penthouse and Viva magazines and he created one of my favorite comic sculptures: President Richard Nixon as a shrunken head**, which he made into a poster that hung on my office wall. Bill also suggested the title of my second book, Man Bites Man: Two Decades of Satiric Art, in which his work was featured prominently.

I haven’t seen Bill in over 30 years (such is the nature of living in New York) and I don’t recall why we ended our friendship (such is the nature of memory loss). Nonetheless, I am convinced this sequence of totally random connections that triggered memories of Bill after three decades was somehow destined to be (such is the nature of paranormal energy).

That night I was trying not to think about the implications of this surprising sequence of events. The next day I contacted Ammon Shea, the man who salvaged and shared Bill’s work with his wife, Alexandra Horowitz, who had written the email to Maira Kalman, who passed it on to Rick Meyerowitz, who forwarded it to me.

Ammon told me in an email that he removed only a very small selection of what was tossed. “My son and I were walking east on 100th between Columbus and Amsterdam last week, and noticed a man headed west, holding an armful of framed pictures,” he recalled. “A hundred feet further on we came to a private sanitation truck, loading what looked to be the contents of someone’s apartment into the back of the truck. It seemed obvious that someone had just passed away, and that their possessions were all being thrown away, without any concern.”

“I saw a large portfolio,” he added, “opened it and saw that it was filled with someone’s art, and thought it was the sort of thing someone somewhere would be glad to see rescued. There were a couple of young men there going through the furniture, and I heard one say ‘no, leave those behind … those are Polaroids … you need special equipment to look at them.’ The ‘Polaroids’ turned out to be a set of binders, filled with Kodachrome slides. These were a mixture of travel pictures and slides of art, and so I grabbed these as well.”

Ammon concluded, “It is, I suppose, entirely possible that the decision to throw all this out was a considered one—I didn’t know Bill Lee, and know nothing of the circumstances surrounding his works and their appearance on 100th Street. But I couldn’t imagine just walking past the destruction of something that was once terribly important to someone without seeing if it could be otherwise handled.”

I suppose we have all seen art discarded in urban trash bins or town dumps. A librarian friend of mine, who has since passed away, made regular rounds of artist studios and the offices of creative institutions to collect discarded artifacts for his research library; he had collected some rare, important items. Over the years, I’ve salvaged pieces of value to me. I always wondered who and why someone would discard personal or professional creations in such an unceremonious manner. How did the art lose its value? Were they failed experiments? Was it an uncontrollable emotion—a release of frustration or anger? Or was the reason more prosaic—an existential shift in circumstance, like moving to smaller quarters or dying?

Whatever the reason, there is something sorrowful about the disposal of art, whatever the perceived quality. Among the material saved by Ammon and Alexandra were drawings from a trip Bill made to Poland to cover the Solidarity era in cartoons, possibly for Penthouse. There was a proposal for a charming book of fantasy, comic animal furniture that was inspired (Bill scribbled on one of them) by his young daughter. Who knows what other items were hauled away to heaven knows where?

I began seeking out clues to my estranged friend’s whereabouts. I was impatient to find a rationale. I recalled that he had lived near 100th Street and CPW, where the bags were found. Before the pandemic I heard he was not in the best of health and required a caregiver to help him get around. I was given his telephone number, which I lost, though I found it on one of the discarded drawings. I dialed the exchange and an expressionless computer-generated voice immediately answered: “This number is no longer in service.” Click.

I found no record of Bill’s death on Google or Wikipedia. I found no personal website. Although he was often published, very few of his cartoons are archived online, even under the tag “Penthouse.” I found a brief biography on a cartoonists’ fan site and wrote to the site administrator but he could not help. “I never actually spoke to him,” he admitted.

Next, I dug deep into my hazy memory for his daughter’s name. It eventually came into focus, so I thought. I also thought she was a professor or college instructor outside of New York, and after a few frustrating hours clicking around faculty databases and trying out variations of the name, I stumbled on a possible match. In fact, I was so certain of it when I saw a photograph of a woman who resembled Bill that I wrote an email to her and waited. Two or three days went by without a word. I eventually looked in my spam folder and found that she had instantly responded:

Hiya Steve,

This is indeed an odd story! I’m sorry to say, though, that I’m not [the person] you’re looking for (there are SO MANY of us).

I wrote to Maira to relate my brief search. She wrote back:

Hi Dear Steve,

I’m sorry this has stirred up so many memories. Isn’t that how it always is. You wake up in the morning and don’t know what’s going to hit you.

Yes, it stirred up something. But more than faded memories, I am distressed that so much original artwork was relegated to the garbage heap. It is not possible to protect and save the gargantuan amounts of artifacts and documents that define an individual’s life on earth; there is not enough time or space to store and care for it all. By this measure a creative life, unless rescued by chance or diligence, is easily reduced to just so much burdensome refuse.

Other than the mystery of not knowing whether Bill is alive or dead, I am haunted by the sad fact that he is just one of too many artists who were not archived or collected, and are now relegated to attics or, worse, a landfill. I am continually asked by many illustrators, cartoonists and designers now in their 70s to 90s or their heirs who are responsible for the work, where to deposit it and how to preserve it. I shrug. There are some museums, archives, libraries and study centers that take donated materials; more extensive and historically significant collections are bought. But not everything can (or should) be saved. Not everything made by an artist has a measurable value. Still, this story provokes a sense of despair.

Preservation is validation. Validation is proof of life. Long ago, I published a fair amount of Bill’s art. Other than what is in Man Bites Man I do not have anything of his—and what I do have (somewhere) are photostats, anyway. Stored but not easily accessible. I am certain I saved tattered copy of the Nixon shrunken head poster. Maybe what remains of his work eventually will find an appreciative home—and maybe the best of it already has. Well, at least for now, some of it is off the street.

**I learned only this morning after publishing this article that “Nixon, The Shrunken Head of State” was a poster for a 1974 exhibition titled “Americarnal” at the SVA Gallery. Thanks to Beth Kleber, archivist of the SVA Milton Glaser Archives and Study Center.

The post The Daily Heller: When Art is Garbage appeared first on PRINT Magazine.