In 1692 the god-fearing Puritans of Salem, MA—possessed by irrationality, fostered by mistrust and riled by hate—accused a number of women and girls of witchcraft. If found guilty, the “witches” and the men in their lives received severe punishments.

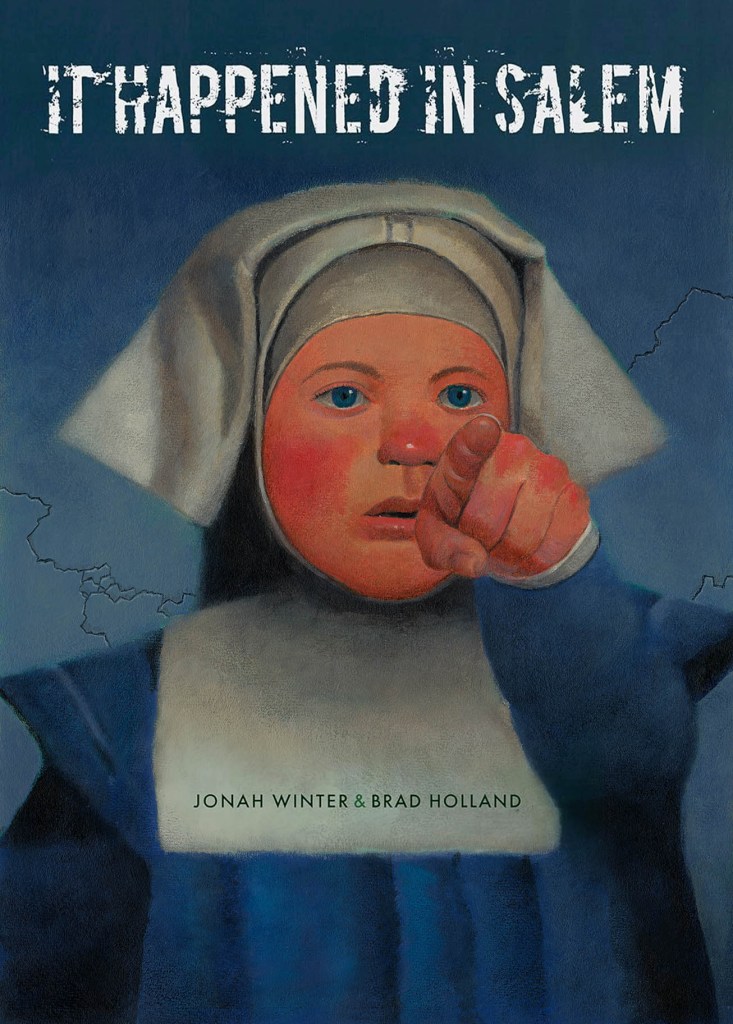

The loathsome act known as witch-hunting continues in today’s vernacular as a shorthand for immoral and extra-legal hounding of persons suspected of some broken social more. It Happened in Salem (Creative Editions), with its cinematic noir-sounding title, is a book about the past for the present, smartly written by Jonah Winter for middle-grade students, with elegant illustrations by Brad Holland.

The subject is perfect for Holland’s blend of emotional intensity and sensitivity brought out in gesture and color—and he tells us more below.

Creative Editions is known as a children’s book publisher that has released books on difficult subjects, including the Holocaust, and now the Salem witch-hunts. It is difficult to think of the trials as being easily explained to children. How did you feel about the tone of the manuscript when you first read it?

Well, the first thing to dispel is the assumption most people make that witchcraft trials were common in colonial times. They weren’t. Of course, there were incidents where people were tried and hanged as witches—it was a holdover from the country’s Old World heritage. But the events that made witch-hunting so infamous actually occurred only during a period of about 18 months, and mostly in and around Salem. So, I think the author presents that accurately. It was a local epidemic of mass hysteria that ran its course and then, when it threatened to harm some prominent people, was suddenly shut down.

The manuscript and your illustrations do not hide the injustice and corruption of the period but vividly reference the continuing comparisons to the present.

Well, yes; in fact, my first thought was that the country had gone through something similar during the children’s daycare scandals of the 1980s. All that hysteria that started on the afternoon talk shows about how children’s preschool centers were hotbeds of satanic abuse—with crazy charges that people were slaughtering kittens and summoning the devil or flying through the air like witches. Innocent people lost their jobs and reputations; a bunch of them went to prison. And then suddenly, just like the Salem hysteria, the craziness ran its course and, with a few exceptions, the media dropped the whole thing as if it had never happened. I thought at the time that it was just like the Salem witch hunts, except that it went on for nearly a decade and was far more widespread—and it wasn’t happening in0 some colonial dark age, either.

Your images are so perfectly suited to the original Salem, with a curious timeless quality. Did you know what you wanted to paint from the outset?

Well, yeah, sort of. To begin with, I was determined not to give the story any kind of spooky glamor, the way movies often did. There were never any real witches, after all, so this was a cautionary tale, not a Halloween story. Back in high school, I had read all of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short stories, so I had a definite background of that era to draw on. And I did start by researching the subject. I found photos online of Salem’s so-called witch houses, and paintings and reconstructions of colonial interiors. I even found articles about the spot in the woods where archaeologists think the hangings took place. But with the exception of historical dress, I thought too many period details might make the story seem like something that happened a long time ago and couldn’t happen again. That’s why in several paintings I just showed the figures against neutral backgrounds. I thought it might make it easier for readers to identify with.

Did you create the images with kids in mind or were you directed in that direction?

No, the pictures were all my ideas and the publishers didn’t ask me to change a thing. The only issue they ever did raise was whether we should show the hangings. They were obviously concerned that that might be too upsetting for kids—and in the beginning, I had wondered about that myself. But ultimately, I concluded that kids these days probably see images in movies and video games that are a lot more violent—more grotesque even—than the matter-of-fact way I was showing what had actually happened. So, I decided to just trust my instincts and do what I thought would tell the story honestly. The publishers were totally supportive, and I was very grateful. I worked throughout with the art director Rita Marshall, and she was terrific.

The images have an age-neutral quality, in the sense that very young kids won’t get it, but mid-range kids who can read on their own or have parents who will help them are the target. Is this true?

Well, my own thinking is based on my background. When I was a little kid, I used to go with my dad on Friday nights to the local soda fountain where we’d get the latest issues of Life, Look and Collier’s magazines. Then we’d go home and he’d read the articles to me and encourage me to follow along. My mother would come by and say, “Walt, you can’t read things like that to a kid,” and dad would just say, “hell, you can read anything to a kid.” So while there are a lot of things that I wouldn’t normally bring up to a child—you have to have some common sense—in general, I tend not to talk down to them. I know that a lot of what you tell a kid will go in one ear and out the other. But if something they don’t understand really makes an impression on them, I trust that it’ll stick in their heads until something in their experience causes a light bulb to go off. In the end, I think it’s okay to let kids wonder what some things mean. It’s like buying clothes for them to grow into.

The hanging of a so-called witch is the most indelible painting of all …

Well, it’s certainly the one that gave me the most trouble. I’ve lost track of how many pencil sketches I did for it. And there were two painted versions that I worked on for days and threw out. But then I started over and finally hit on this one. The text on the facing page was about how many people had been hanged. So at one point, I had an image of several people dangling from a tree. And even in this version, I once had five. But then, suddenly on impulse, I just painted them all out but one. Then I redesigned the tree into a kind of an X on the page, with the figure of the woman at the intersection of the X. It was a sort of design solution to keep the image simple. And it seems to make the picture more moving. I don’t think I could have thought that out in the beginning though. It’s just that as I worked on it, it kind of worked itself out.

Also, I cannot get the slave girl text and image out of my head.

Yes, I think that’s really my favorite painting from the book. And it’s based on a real person, too, except that nobody knows what the woman actually looked like. According to legend, her name was Tituba and she was the first person to be accused of witchcraft. Originally from Barbados, she had been brought to Salem as a household slave by the town minister, Samuel Parris. It was his young daughter and niece who first accused her. In the beginning, she denied the charge, but finally confessed—allegedly after being beaten—and to save herself, began telling preposterous stories that implicated two other women as witches. That’s how the mass hysteria began. It lasted for about a year and a half. Tituba was imprisoned for the whole time but was never tried, and when they finally released her, she disappears from history.

What other images do you feel have the most impact amid all the powerful ones herein?

I think the strongest picture is the last one, the little girl cherishing the voodoo doll. It began when I was doing research for the way kids dressed in those days. I kept finding old daguerreotypes of little girls holding a beloved doll. Apparently, that was a cliche of early photography. So that immediately gave me the idea for the painting. I researched voodoo dolls and used bits and pieces from several of them. And then I decided to make the girl so young and innocent-looking that her expression wouldn’t be much different from what you’d expect from a dog or a cat. The idea of poisoning and weaponizing a little kid’s mind is so obviously evil that, to me, that was the real story behind the story of the Salem witch hunts.

Do you think that an audience that has never known about the Salem trials will accept this knowledge?

Well, I suspect that like most things in life, different people will get different things out of it.

I have to admit, although I have long had knowledge of the trials and grew up hearing about modern witch hunts, your book has reinforced my trepidation of these things happening again. Did it have a similar effect on you?

Well, imagine how much more damage they could have done in Salem if they had had the internet, social media and artificial intelligence to work with. They could have turned what was essentially a local scandal into a global one. Which brings us up to today. Unfortunately, the one thing you can learn from history is that most people never learn from it. Human nature is pretty intractable, so things that happened once upon a time are always likely to happen again. I suppose that’s why we need cautionary tales.

The post The Daily Heller: Witch Hunts in Olde Salem, MA appeared first on PRINT Magazine.