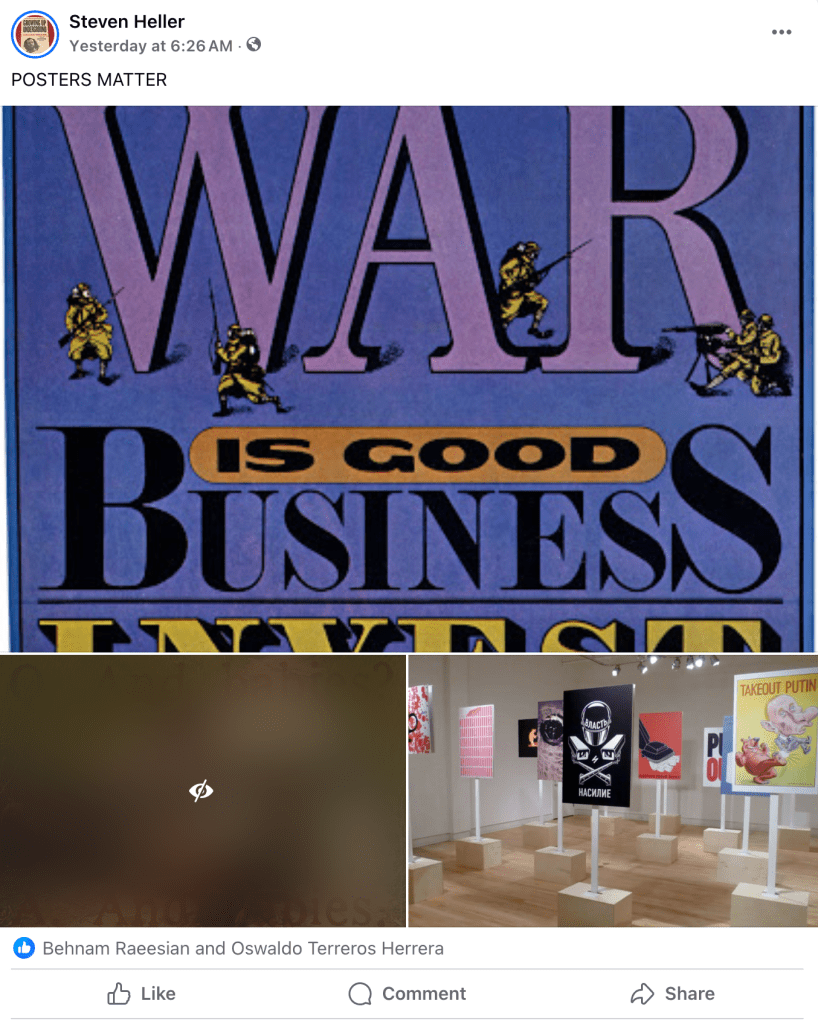

The other day I made a Facebook post with the headline “Posters Matter.” Of course, that’s a riff on the title of Debbie Millman’s podcast Design Matters—the point, obviously, being that the three posters I posted connected with their audiences and made a cognitive difference. Included were Seymour Chwast’s “War is Good Business, Invest Your Son,” “And Babies? … And Babies,” and an SVA gallery exhibition, Russia Rising: Votes for Freedom, which opened in 2012. As you can see, one of the three images didn’t make the Meta cut.

I was surprised, as I’ve never had this happen in all the years I’ve been posting on Facebook. At first I was angry. This poster is comprised of an iconic photo that arguably changed the way the American people viewed the so-called “collateral damage” inflicted by GIs during the Vietnam War. Combined with other photographic documentation readily found uncensored everywhere on the internet (e.g., a napalmed child running down a road, a Viet Cong prisoner being shot in the head by a South Vietnamese police commander, a Newsweek cover featuring a young weeping Vietnamese mother holding her dead child, and so many more), this poster became the pivotal message of antiwar protest. Given this history and its ubiquity, to have it “covered according to our Community Standards” is either a misapplied algorithm or a telltale act of prior restraint or, worse, censorship.

Facebook’s rationale:

This photo may contain violent or graphic content.

We remove things that go against our Community Standards. This photo does not go against our standards, so you can choose to see it.

• We use either technology or a review team to identify content that should be covered.

• Graphic content may include things like animal abuse, death, wounds, someone’s life being threatened or suicide and self-harm.

• Graphic content isn’t visible to people under 18.

The image was not removed but rather highlighted as a potential problem. And herein lies the root of my ambivalent dismay. Facebook did not censor the image per se, but it is making a critical judgement that is reminiscent of placing “offensive” publications in brown bags or airbrushing out unseemly content. While I do believe media (and especially social media) has a responsibility to caution viewers, listeners and readers—as most regulated media does—about certain taboo conventions, it also subliminally passes sentence on what is being revealed. Who decides what these “community standards” are, in any case?

Newspapers, magazines and television all have Standards and Practices managers. I experienced this firsthand when, working at the New York Times, I was given access to a server that held vivid and gruesome outtakes of suicide bombings. Judgements regarding appropriateness were made based on how extreme the barbarity was. If the consequences of the event could be shown without showing dangling limbs and disfigured bodies, a less-intense image would be published. In theory I do not disagree with the principle. But “And Babies?” is a historical document that exposes a terrible crime and evidence of an unpopular war’s apparatus run amuck. While the cautionary spirit is sound, the practice is flawed. Meta should review its own standards and policies toward policing content vs. free speech.

The post The Daily Heller: A Meta Review of Meta’s ‘Community Standards’ appeared first on PRINT Magazine.