As Donald Trump disrupts international trade, sends suspected gangsters to indeterminate imprisonment in a Salvadoran hellhole without due process, wages war on the right to counsel, abandons American allies, and throws Ukraine under the bus—as Donald Trump does, in other words, pretty much what he promised—I haven’t written anything about this mess beyond retweeting the work of more energetic writers. Trump wants to make the United States a Peronist nation, and a whole lot of people voted enthusiastically to go along with his mad ideas. Having watched friends and former allies enthusiastically embrace Trumpism, I feel like the loved ones of a smallpox victim after vaccination but before effective treatment. Yes, the illness might have been prevented. But now that it’s here, all we can do is let it run its course and hope the patient survives without too many scars.

I’m both comforted and disheartened by historical perspective. Human history is as much a story of folly, ignorance, and cruelty as of genius, perseverance, and generosity. In particular, my recent reading of Christopher Cox’s Woodrow Wilson: The Light Withdrawn is both encouraging and frightening. Someone—Jonah Goldberg, maybe?—called Trump the worst human being to occupy the White House since Woodrow Wilson and, notwithstanding some notable villains, that seems about right. Cox makes the case that Wilson was awful on about every dimension imaginable. As president, he sought tyrannical powers with frightening success. But the nation survived him.

Sort of. Wilson inflicted lasting damage on the body politic.

An arch-segregationist even for his day, Wilson most notably imposed new restrictions on black Americans in the federal workforce and the District of Columbia. He worked hard to eliminate exceptions to Jim Crow, with devastating effects that lasted decades. He also expanded the president’s powers in ways that echo to this day. Unilateral tariffs and threats to annoying law firms are exactly the sort of Mad King antics he would have loved. 1

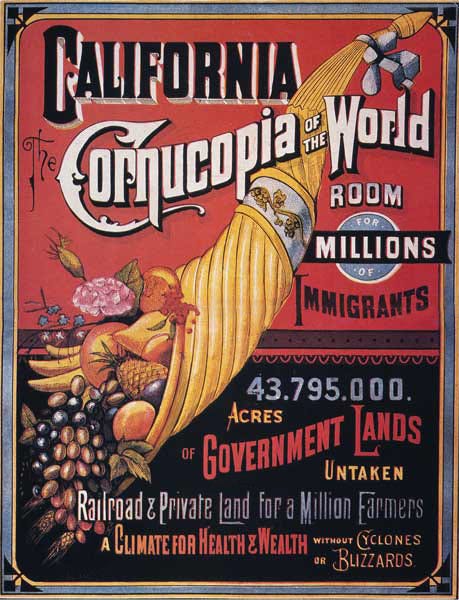

Wikimedia

I spend most of my time these days working in the progress and abundance movement, in the hopes that once the Trump plague passes, the world can move in a positive direction. Much of that work takes place behind the scenes, commissioning articles for Works in Progress (pitches welcome!), attending conferences like a recent one on housing pluralism organized by Steve Teles and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins, and occasionally advising up-and-coming writers. I recently reviewed Abundance, the book-of-the-moment by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, for Reason.

Here’s the opening of my review:

At the turn of the 20th century, labor leader Samuel Gompers had many specific demands, including job security and an eight-hour day. But his list of “what labor wants” added up to a single overarching—and open-ended—desire. “We want more,” Gompers said in a 1890 speech. “We do want more. You will find that a man generally wants more.

More was once the essence of progressive politics in America: more pay for factory workers; more roads, schools, parks, dams, and scientific research; more houses and education for returning G.I.s; more financial security for the elderly, poor, and disabled. Left-wing intellectuals might bemoan consumerism and folk singers deride “little boxes made of ticky-tacky,” but Democratic politicians promised tangible goods. The New Deal and the Great Society were about more.

In the early 1970s, however, progressives started abandoning the quest for plenty. They sought instead to regulate away injustice, pollution, and risk. The expansiveness of President Lyndon Johnson and California Gov. Pat Brown became the austerity of President Jimmy Carter and California Gov. Jerry Brown. Activists unleashed lawsuits to block public and private construction. Government spending began to skew away from public goods like parks and roads and toward income transfers and public employee compensation. Outside the digital world of bits, regulation made achieving more increasingly difficult if not downright impossible—in the public sphere as well as the private.

With the presidencies of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, the politics of more came to mean giving people money or loan guarantees to buy things: houses, college degrees, child care, health insurance. But regulation grew along with the subsidies, and the supply of these goods didn’t expand to meet demand. The subsidies just pushed up prices. Instead of delivering bounty, government programs fed shortages, and shortages fed anger and resentment. “Giving people a subsidy for a good whose supply is choked is like building a ladder to try to reach an elevator that is racing ever upward,” write Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson in Abundance.

Klein and Thompson believe in supply-side progressivism, a term Klein coined in a 2021 New York Times column. Abundance is their manifesto on behalf of “a liberalism that builds.” The authors want an activist government to emphasize creation rather than restriction, generating abundance rather than stoking resentment. Although concerned about climate change, they have no sympathy with the degrowthers who invoke it to argue for shutting down industry and imposing stasis. Making people worse off, they believe, is not a progressive cause.

You can read the full review here.

As an author, I believe strongly in reviewing the book the authors were seeking to write rather than the book you would have written yourself. Who is the audience, and what are the goals? In this case, the book is a manifesto explicitly addressed to people to the left of center who believe in technocratic governance. The authors are seeking to pull their fellow progressives away from those who advocate “degrowth,” who burden government projects with requirements unrelated to their purposes, or who sue to block any specific kind of construction. Building an alliance of abundance progressives is a worthy goal.

I also believe that politics works through coalitions of people who share some important goals but disagree about other things. Right now, that means my progress and abundance allies include not only people who share the bottom-up, market-oriented perspective of The Future and Its Enemies but also top-down technocrats like Klein and Thompson.

That said, Josh Barro had a telling critique with important political ramifications. To put it bluntly: The authors are either naive, ignorant, or dishonest about energy:

At the event on Monday, Klein responded to my question — if you can make energy this cheap, why don’t you think you can convince Republicans to want what you’re offering? — by pointing out that there is rising hostility among Republicans to clean energy investment, even when the market demands it. Legislators in Texas are considering new laws that would impede that state’s rollout of wind and solar power generation, which has to date put California’s to shame. The president has his own quixotic grudge about windmills. And I certainly understand the idea that it’s pointless to argue with people about their goals. Still, if we take their energy vision seriously, it’s a vision they are claiming would serve not just liberals’ goals but also conservatives’ — since conservatives have long demonstrated a love of cheap energy. It doesn’t seem like as hard a leap as some of the others they take in the book, like trying to convince affluent people to want tall apartment buildings in their neighborhoods.

The problem, I think, is that Klein and Thompson don’t quite believe in their own energy vision. The suite of policies they advocate suggests they believe their agenda as a whole would grow the economy and raise standards of living. (And I agree). But it also suggests they still view decarbonization as a cost center. They would take some of the gains from a pro-abundance policy agenda and plow them into the green transition — maybe producing a higher standard of living than if you didn’t change policy at all, but producing a lower one than if you unleashed abundance in the economy while allowing users of energy to seek out the cheapest possible source, whether fossil or renewable.

Of course, advocates of decarbonization would argue that reducing carbon emissions is itself a benefit — a component of abundance. But the benefits of decarbonization are diffuse: they arise all over the world, and disproportionately in lower-income countries that are less prepared to adapt to climate change. They also mostly accrue far in the future. Meanwhile, the cost of decarbonizing the US economy is borne almost entirely in the US, and in the near term. This is why carbon-reduction policy comes into conflict with a politics of abundance (and also why it’s so politically difficult to implement): It imposes costs on the voters who get to pass judgment on the policy, while producing benefits that mostly go to foreigners, a lot of them not yet born.

So if the calculation is that a decarbonization agenda leads to abundance because it will lead to higher global GDP in 2080, with the benefits concentrated in poor foreign countries, even as the investments required for it will raise costs in the United States over the next couple of decades — well, that’s not likely to be perceived by US consumers as increasing abundance, and certainly not as helping them get a big-ass truck.’

The ecomodernists at the Breakthrough Institute, who are all in on nuclear power, have an answer: Build many, many more nuclear power plants and use the clean electricity they generate to power a mostly electrified economy. In an Atlantic article, Thompson himself wrote:

What if I told you that scientists had figured out a way to produce affordable electricity that was 99 percent safer and cleaner than coal or oil, and that this breakthrough produced even fewer emissions per gigawatt-hour than solar or wind? That’s incredible, you might say. We have to build this thing everywhere! The breakthrough I’m talking about is 70 years old: It’s nuclear power. But in the past few decades, the U.S. has actually closed old nuclear plants faster than we’ve opened new ones. This problem is endemic to clean energy. Even many Americans who support decarbonization in the abstract protest the construction of renewable-energy projects in their neighborhood.

But the book de-emphasizes nuclear power and it certainly doesn’t address guys who think big-ass trucks are an important example of abundance.

Right now, the progress and abundance movement is made up mostly of intellectuals, policy wonks, and business people. It desperately needs a stronger manifestation in practical politics and, at the moment, that means a big new Democratic party faction that rejects the economic populism of the Elizabeth Warren-AOC-Bernie Sanders wing, foreswears “everything bagel”2 approaches to public goods, embraces pluralism rather than the grievance politics of right and left, and welcomes former Republicans and independents as allies.3 Pro-abundance Democratic candidates no longer need to placate the party’s leftists. Trumpism has created an eager audience of now-homeless voters who can be enlisted as Abundance Democrats, while casting Warren Democrats into the political wilderness.

A charismatic representative would help.

Despite sympathy for the diligent foreign policy wonks of the Wilson Center International Center for Scholars, and acknowledging the duly enacted (but idiotic) law that created it as a memorial to that monster, I can’t completely mourn Trump’s actions against it. ↩︎For the record, non-metaphorical everything bagels are disgusting. ↩︎Ideally, they would learn a lesson from the disaster of Covid lockdowns and put students and parents, rather than teachers’ unions, at the center of their education policies. ↩︎

Virginia Postrel is a writer with a particular interest in the intersection of commerce, culture, and technology. Author of The Future and Its Enemies, The Substance of Style, The Power of Glamour, and, most recently, The Fabric of Civilization. This essay was originally published in Virginia’s newsletter on Substack.

Find Virginia’s recommended reading on this topic in her original post.

A Colony’s Windows, from the NASA collection Space Colony Art from the 1970s by Rick Giudice, Public Domain Archive.

The post Waiting for the Fever to Break appeared first on PRINT Magazine.