The last time I spoke to Brad Holland before he died last month, he was busy trying to finish the final batch of paintings for his solo exhibition at Cristina Taverna’s Galleria Nuages in Milan, which represented Milton Glaser, Paul Davis and Jean-Michel Folon. Davis had suggested Taverna should know Brad Holland. Her response was, “Who is Brad Holland?” To which Davis replied, “Brad Holland is the Elvis of American illustration.”

Taverna came to New York to meet Holland at his Soho loft. “While there,” recalls Brad’s friend and colleague Chuck Pennington, “she asked Brad specifically about a few paintings and he explained that they were for a Shakespeare book project that he had in mind.”

Neither one of them forgot that conversation, and in 2015, Taverna asked Brad to create 12 paintings for a special edition of Oscar Wilde’s Happy Prince. Coinciding with the book’s release, the gallery exhibited the original paintings, and now all 12 reside with a single collector in Italy.

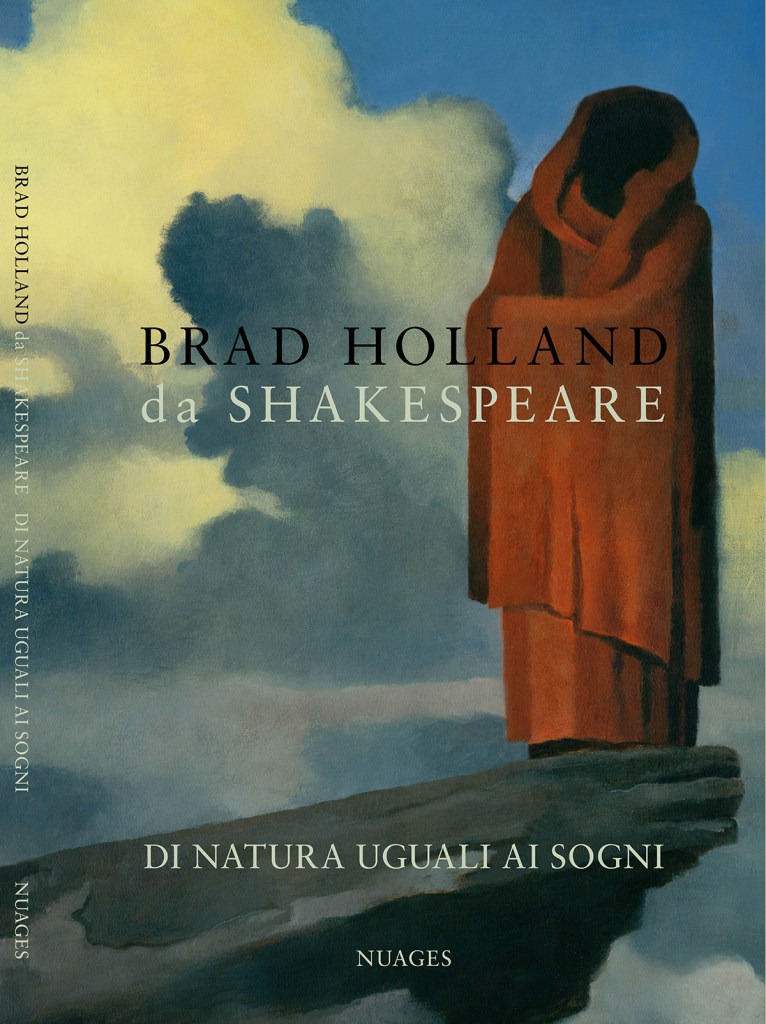

Then, “In the summer of 2024, Cristina called Brad and said, ‘Let’s do the Shakespeare book.’ Shortly after, Brad called me and asked if I would help him with the book,” Pennington adds. “At that point, he already had about 20 completed paintings for the book. The challenge was that he needed to produce another 20 or so. The other challenge was that the book was going to be published in both Italian and French (Brad and I spoke neither language). Cristina would publish the Italian edition for her gallery, and Martine Gossieaux would at the same time publish a French edition for her gallery in Paris. Once the book was complete, each gallery would then exhibit the originals one month apart.

“Over the next few months, Brad completed more than the needed 20 additional paintings and together we finalized the book. However, Brad continued to rethink and rework the paintings right up to the day we released the files to the printer in Italy.”

I never knew an hour or minute when Brad was not in the throes of finishing artwork to send off to an expectant client or patron somewhere in the world. So, I was not surprised. What did shock me was that these artworks, titled in English Such Stuff As Dreams, would be his last, and that his compulsion to complete them and attend the opening in Milan was a fatal decision.

Italian version © 2025 Edizioni Nuages – via del Lauro 10 – 20121 Milano

Pennington was well aware of Brad’s ongoing heart issues and the planned hospital procedure. “I asked him numerous times if we could delay the Shakespeare project until after his heart surgery and, in fact, the show was delayed twice due to his health. But when Brad finally agreed to a date in March, he wasn’t going to be deterred. My only goal at that point was to work as quickly and as efficiently as I could on my end.

“I’m still amazed in some ways that the book and the show even happened,” Pennington continued. “Even more amazed that Brad gathered up the strength to be at the gallery opening in Milan. But this homage to Shakespeare was so important to him.”

It is also important to those of us who care about Brad—the last achievement of our “Elvis.” Below I am publishing a selection of the paintings and the excerpts from his introductory essay, which celebrates the triumph of the show.

(Books are available in Italian and French editions.)

All art and text is © Brad Holland / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

French version © 2025 Éditions Martine Gossieaux56, rue de l’Université, 75007 Paris

My first brush with Shakespeare.

I was packing to catch a plane for Finland and Norway when a small Midwestern publisher phoned to ask if I’d do the book covers for nine plays by Shakespeare. He faxed me a list of the titles they intended to publish, and I took a book of Shakespeare’s plays with me to read on the trip. In Oslo, at a bookstore on Karl Johan’s Gate, I bought a book of Elizabethan portraiture for costume reference. Then I began the work auspiciously by sketching out cover ideas in an elegant suite at the city’s Grand Hotel.

I had come to the Nordic countries to speak at a photojournalism conference in Finland and then to Oslo to give a talk to Grafil, the Norwegian graphic art organization. Bernie Blach, representing Grafil, met me at the airport. We were old friends by this time, having met more than a decade earlier on my first trip to Norway. He taxied to the hotel with me and waited in the lobby while I stowed my luggage upstairs.

I had stayed in rooms at the Grand Hotel on previous visits, but nothing like the labyrinth the organization had booked for me this time. I never thought to count the rooms, but it was a luxurious suite, with several bedrooms and bathrooms, each with a built-in television, a massive living room full of beautiful furniture and art objects, a conference room and a dining room table for a dozen people or more.

“Is the room OK?” Bernie asked when I rejoined him in the lobby. Feeling a little embarrassed, I said “I really don’t think I need that much space.” He laughed. “It’s the Nobel Suite, he said, “where the Nobel Prize winners stay.” “Great,” I said. “Now if I ever win a Nobel Prize, they can just mail it to me.”

The covers I began in that luxury suite all those years ago were to become the starting point for the paintings in this book. However, my first brush with Shakespeare came years before that, when I was 10 and discovered a Classics Illustrated comic book in a rack at the grocery store where I used to mow the lawn every week.

The image on the cover had jumped out of the rack at me and made me wonder about the story it illustrated. Yet I didn’t think to buy the comic book that afternoon. I don’t know why, maybe it’s just because it was hot that day and I was sweating and had a long way to go pushing the lawnmower back home. Yet the image of the guy with the donkey head stuck in my head like a song you can’t get rid of. So, a few days later when I was downtown, I dropped in at the public library to see if I could find A Midsummer Night’s Dream in a real book.

At 10, I was well aware of Shakespeare’s name, of course. It was one of those names you just hear as a kid, like Plato, or Rembrandt or Dizzy Dean, people who you know of without really knowing about, but which, as the years go by, you tend to pick up clues.

In the case of Shakespeare, I knew that he had been a medieval writer of some kind and had authored a play called Hamlet. And I knew that he was famous for having written “to be or not to be”—whatever that was supposed to mean. But beyond that, he was not much more than a name to me, and for all I knew, he might as well have been a guy with a donkey head.

Hallie Grimes, the town librarian, knew me by sight. I had been a regular at the library since kindergarten, but it always gave me the creeps when I walked through the door and saw her look up at me from her work. She reminded me of the squinty-eyed old ladies you sometimes encountered in dark run-down houses when you went door-to-door selling Boy Scout candy.

I didn’t know where to start looking for Shakespeare’s books. The library had an official Young People’s Section right next to the checkout desk, where the ever-vigilant Hallie could keep a sharp eye on the small fry whose parents always plunked them down there. But by fifth grade, it had long been my custom to steal away from this fishbowl where I had already read Treasure Island and Kidnapped and the other Scribner’s Classics, and to roam through the stacks back in the section of the library where elderly gentlemen could always be found sitting in stuffed chairs before a large picture window reading newspapers mounted like flags on bamboo sticks. …

But when I brought the big volume to the check-out counter, Hallie Grimes glared at me with the cold eye of a fortune teller. She inspected me and asked me how old I was. Older than I look, I told her. Well, you know, she warned, Shakespeare can be very heavy-going. There were lots of big words in his plays, archaic words too, things that could cause even a college professor to scratch his head. “Are you sure you want to take this out?” She reminded me that there were plenty of “age-appropriate books” for kids like me in the Young People’s section, right over yonder.

Miz Grimes was a hard lady to dispute, but I gave it my best 10-year-old try. I can’t remember exactly what I said to her, but I doubt that it was very eloquent, and in any event, it wasn’t persuasive. Hallie Grimes just looked at me as if I were cutting across her lawn. OK, she said. Let’s try a little test to see if you’re old enough to be reading Shakespeare.

She opened the book, and paged through it until she got to Hamlet, and then to Hamlet’s famous soliloquy. This is the most famous passage in all of Shakespeare, she informed me, one of the most famous in all of literature—and asked me to read the whole thing to her out loud. If I could do that, she said—and if I could then tell her what the speech meant, or what it was about—she’d let me borrow the book. Well, I thought, she runs the library; what choice did I have? So, I began reading softly in my best library voice. It was an inauspicious start:

“To be or not to be, that is the question …” There it was—that damned phrase! The one Shakespearian quote I had been hearing all my life, and it didn’t make any more sense to me this time than it ever had. So, I skipped over it quickly, hoping that if I didn’t slow down, The Grand Inquisitor might not quiz me about it—and I soldiered on. …

In the speech, of course, Hamlet is lamenting the “sea of troubles” besetting him and considering suicide. That’s what he means when he considers “making his Quietus” with a “bare Bodkin”—ancient English for an unsheathed dagger.

But for a fifth grader still acquiring a grip on modern English, I had no idea what a “Quietus” could possibly be. And as for “a bare Bodkin,” it sounded like an overly cute phrase for a “bare body.” So, if I had to guess (which, of course, I did) I could only imagine that Hamlet was planning to do something with a naked girl.

But how does a 10-year-old boy say that to an elderly lady librarian?

Realizing that I had been out-foxed, I admitted to Hallie Grimes that I didn’t have a clue about what the speech meant—and that seemed to satisfy her. “Well, one day you’ll be old enough to read Shakespeare,” she said with great satisfaction, and placed the book back on the dolly for reshelving. She smiled at me as I left the library.

But I remember thinking as I headed home across the State Street Bridge that afternoon, that not only did Shakespeare write stories about really cool characters with donkey heads, his plays must be pretty dirty as well.

So much for my first brush with Shakespeare. Now about my latest.

The paintings in this book aren’t really intended to be illustrations for Shakspeare’s plays, although some probably come closer than others.

But in some cases, I’ve taken some of the same kind of liberties with Shakespeare’s plays as he apparently took with the histories of Plutarch and Holinshed, which he mined for plots, passages and characterizations, but tended to bend to his own purposes. Considering the evidence from Shakespeare’s plays, the historian Will Durant once concluded:

“His classical learning was casual, careless and apparently confined to translations. … He made historical faux-pas unimportant to a dramatist: put a clock in Caesar’s Rome, billiards in Cleopatra’s Egypt. He wrote King John without mentioning Magna Carta, and Henry Vlll without bothering about the Reformation. … He knew the more startling of Machiavelli’s ideas, he referred to Rabelais, he borrowed from Montaigne; but it is unlikely that he read their works.”

Yet despite the liberties he took with his source material, Durant concluded that “Shakespeare is Shakespeare—pilfering plots, passages, phrases, lines anywhere, and yet the most original, distinctive, creative writer of all time.”

I wish Hallie Grimes were still alive. I’d like to go back home to Fremont, OH, for a day or two, visit the venerable old Birchard Library and give her an inscribed copy of this book.

— Brad Holland, New York City, 2024

The post The Daily Heller: Brad Holland’s Last Exhibition appeared first on PRINT Magazine.