On July 11, Tokyo’s Kura Gallery opened an expansive exhibition, Fracture: Japanese Graphic Design 1875–1975, on view until July 26. Its curator, designer, educator, and historian Ian Lynam, created the exhibition as “an archive-on-display” of many of the objects and artifacts featured in the recently published hybrid coffee table book/textbook of the same name. Both the book and exhibition explore graphic design in Japan from its foundations in the graphic arts and crafts, through the industrial, wartime, and commercial periods, to the pre-digital design era. The exhibition also features Japanese-designed objects that tether it to Western/hybrid ideas of modernity, imperialism, gender, commercialism, sexuality, and aesthetics.

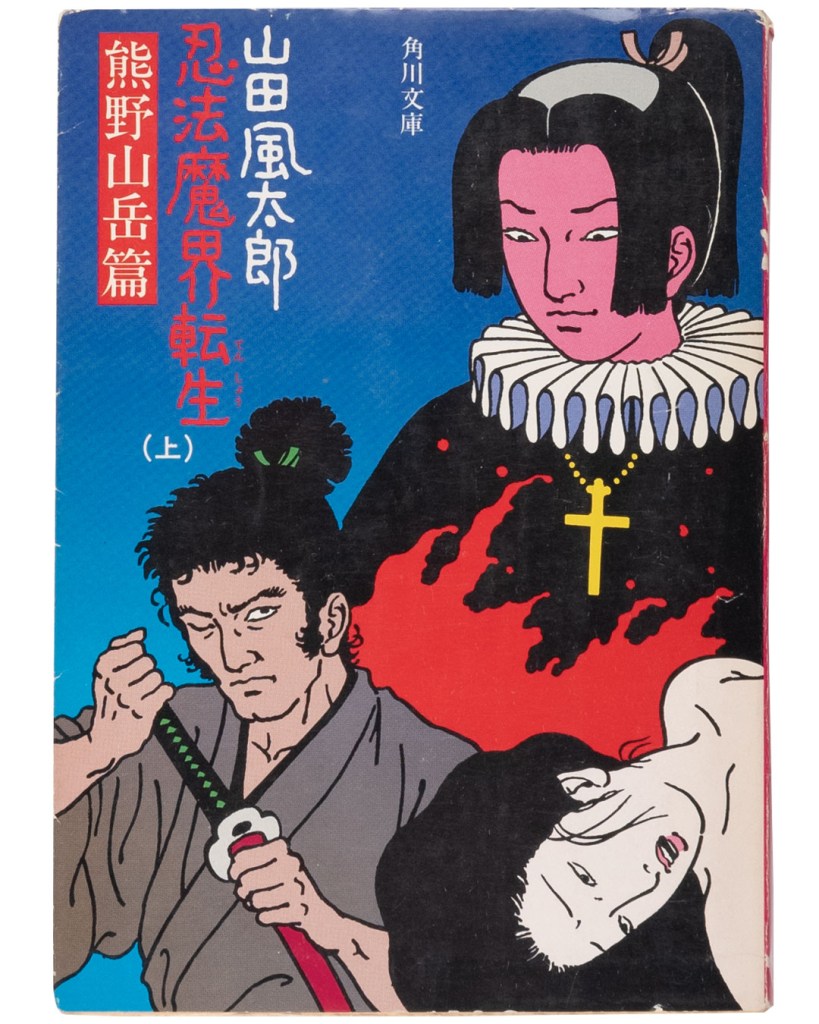

The exhibition contains a number of pieces which date back 100 years — from a kimono with highly decorative Art Deco surface designs to Japan’s very first commercial art publications. The design guidelines for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics are on view, as are a sampling of Japan’s early radical feminist and first mass-distributed LGBTQ+ publications. There are beautiful giant multi-color posters by some of Japan’s graphic design superstars, like Yokoo Tadanori, as well as decorative posters by lesser-known designers.

I asked Lynam to explain the differences between this history and others that preceded it; influences of the past and the West on Japanese history; and why the word “Fracture” is an apt title for this assembly of work.

In an essay on Medium, you write that Fracture is a “robust story of Japanese graphic design history outside of a hyper-simplified Modernist/advertising-oriented rubric in any language. It is a history book, warts and all.” How did you come to live in Japan for 20 years and decide to write this particular book?

As I always say, “I came for love and stayed for the food … then found love again.” Seriously, though, I was absolutely bowled over by the visual culture of Japan when I first came here in 1998 on tour with a band—so much so that when moving here became an option due to life circumstances in 2005, I didn’t bat an eye. I have spent so much time in bookstores and libraries here since arriving, trying to gain as deep an understanding as possible. I started writing for Idea, Japan’s oldest graphic design magazine, a few years after moving here, and the encouragement of many of the editorial staff over the years—notably former editor-in-chief Kiyonori Muroga—led me to believe that I might be able to pursue writing a history of Japanese graphic design that was more expansive.

At the same time, having worked for many years at VCFA in the MFA graphic design program, I was in dialog with others who are interested in more inclusive approaches to design history, like Natalia Ilyin, Silas Munro and Tasheka Arceneaux Sutton, who kept me in conversation about how one might expand histories beyond the “advertising-oriented-Modernist-as-hero clothesline.”

What do you include in the “warts-and-all” category, and why?

One of the most notable “warts” is the wartime propaganda design work of legendary designer Kamekura Yūsaku. His complicity in graphically covering up genocide in occupied Manchuria for the magazine Nippon, published by Yonōsuke Natori’s multi-tiered publishing house Nippon Kōbo, is something that designers should know about. Kamekura is revered—and with good reason, due to his contributions to graphic design—as the equivalent to Paul Rand in Japan, but most people aren’t aware of the darker bits. The warts are essential.

From where does the title Fracture derive?

As I wrote in the intro to the book, “Japan is a nation which took over large parts of Asia, lost it all, and has since turned inward, both pondering and shouting its schizophrenic place in history quietly and aloud.”

One can see this daily on the streets of Tokyo: black trucks festooned with imperial flags outfitted with huge, impossibly loud sound systems, operated by networks of far-right ultranationalist groups known as uyoku dantai, which blast assorted embassies with both live and recorded propaganda, bleating out their demands for the emperor to be returned to power.

Meanwhile, common people aren’t particularly interested in revisiting the horrors of war and pan-Asian imperialism, nor generally interested in national politics at all, frankly. Only 53.8% of voters bothered in the last national election.

Japan has a conservative right-wing government that serves up universal social healthcare for those that live here. To Americans, I imagine that must sound like pure paradox, if not fracture.

What is the relationship between the simplicity of Japanese craft and the clutter of commercial art? Are these both indigenous aesthetics in Japanese art and design?

These are the kinds of restaurant ads that get delivered to my mailbox daily. In Japan, providing extensive information is often perceived as more thorough and trustworthy, as opposed to minimalist designs that may be seen as lacking or even suspicious. This preference for comprehensive details stems from a cultural emphasis on careful decision-making and a desire to have all options clearly presented.

At the same time, the decoration-free craft objects of mingei and similar artefacts often associated with tea ceremonies, as envisioned by Sen no Rikyū, started out as aesthetic rejections of Chinese ornament.

What is significant about 1875–1975?

Japan reopened to the world in 1868 with the Meiji Restoration, and very rapidly industrialized and Westernized. By 1875, there was a full-blown culture of commercial art. 1975 predates the arrival of digital processes in graphic design in Japan, and the rather immediate acceleration of how graphic design was made.

This 100-year slice covers the development of commercial art in Japan and, Postwar, its legitimization as graphic design via Japan’s “economic miracle.” These particular years were also chosen because they allowed me to tell a robust history of Japan, as well—most graphic design history is taught without much context, and I wanted to be able to explain as much social and cultural context as possible to reinforce why different eras of Japanese graphic design look the way that they do.

You say that you are not a hoarder, but how would you technically or personally describe your collection of artifacts?

I’m very interested in the cross-section of unsigned, uncredited commercial art as much as work that has cultural resonance to both more narrow and wider audiences. I love stories, and my collection of artifacts represents narratives that cover wide swaths of history and are evidence of social and cultural change and evolution. I am interested in objects that have meaning, though I am also interested in idiosyncratic meaning, as well. I am not a completist. For example, I have a large collection of back issues of Idea magazine, but I do not want to have every issue. I want the ones with the work that is both “good” and weird.

I was interested to read, “In English, there was the book The Graphic Spirit of Japan by Richard Thornton, a book that I find deeply problematic because of its lack of deep research and the author’s reliance upon Katsumi Masaru, Japan’s top design tastemaker and captain of industry in the Postwar era, for source material.” Do you believe that this book was at least a stepping stone, or was it a stonewall?

Of course it was an initial stepping stone, though I quickly became critical of it because it was obvious who the actual architect of the book was. Masaru-san was involved in every meaningful design organization linked to industry in his lifetime and he literally kickstarted lengthy and successful careers of younger designers he favored, like Tanaka Ikko and Sugiura Kohei, meanwhile brokering corporate, governmental and private alliances that made millions. How history is represented in The Graphic Spirit implicitly espouses that worldview—that the only designers worth paying attention to were the very well-paid captains of industry. I think that is only one part of a much larger story, and Fracture does that.

This is something of a rhetorical question, but why have many of the histories or surveys of Japanese commercial design been written by the non-Japanese?

The poet Oslip Mandelsam wrote about this in 1923: “My century, my beast, who will manage to look inside your eyes and weld together with his blood the vertebrae of two different centuries?”

I think that a lot of it has to do with the power of the work and the disconnect with language. Most non-Japanese folks who have approached writing history surveys of Japanese design have stuck to objects or posters, as they are easier to understand than trying to unpack the interior typography as well as the cultural context of something more dense like Hagiwara Kyōjiro’s 1925 book Shikeisenkoku (Death Sentence). So sure, there are surveys written by non-Japanese, but most of them aren’t very rich in detail or context.

Surveys have been written in Japan, but I think that it is quite difficult to write a history when one is mired in one’s own culture. Because of this, the most well-known Japanese survey of modern design, A Century of Graphic Design グラフィックデザインの世紀, is more of a thin guidebook to, again, the Modernist advertising hero figures. Issue 369 of Idea covers Japanese graphic design from 1990–2014, but due to space and time constraints, it is primarily images and captions.

Do you plan on pursuing your passion for this subject more?

Of course! First off, some friends and I are putting together an independent online course at japandesignhistory.com. This way, folks can enjoy the content in an expanded way that exceeds any notion of what an “online class” might be—we have Japan’s most incisive graphic design historians in dialog. The class covers Japanese graphic design history from the Meiji Restoration until today, with a lot of great footage out and about in Tokyo and nearby areas. The course will debut this fall.

I am coordinating the Japanese language version of Fracture presently, and I am working on another title about the history of graphic design publishing in Japan, as well. We’re also wrapping up my Japanese graphic design history class at Temple University Japan this week, and I’ll be teaching that again next semester, as I always do.

Finally, what does the exhibition do that the book does not (or vice versa)?

More than half of the objects in the exhibit is stuff that couldn’t fit in the book. There are vitrines showcasing objects and publications, as well as dozens of posters on the walls, but there are only a sprinkling of hero-objects that the audience will be familiar with.

One of the highlights for me is that two copies of the same 1968 Tokyo Print Biennial poster designed by Yokoo Tadanori are included—in this way, graphic design as something largely defined by its mass communicative function is underscored. (I’m giving away 100 pieces of identical packaging design from 1923 by Sugiura Hisui—Japan’s first famous graphic designer—at the opening tonight as well.) Ever since I was young, I have been excited about multiples more than lone works. I hope that excitement is infectious.

I’ll be giving a handful of guided bilingual tours, where I crack open the display cases and walk people through the material. As a design and design history teacher, I’m really excited for this—books are great, but talking with folks is the best.

The post The Daily Heller: Japanese Design’s Schizophrenic Place in History appeared first on PRINT Magazine.