When I initially interviewed the writer and editor John Kelly over a year ago he was putting the final touches on his real live ink-on-paper printed magazine titled Dummy about comics, comic artists, cartoons and cartoonists. “After reading the first issue, featuring oral histories on ‘The Art of Pee-wee’s Playhouse,’ I was excited to get to the bottom a minor enigma. Why did he call it Dummy? Would it, in fact, just be a “dummy” in the jargon of publications for a rough layout or speculative magazine, or would it evolve into a real mag for an issue or more?

He successfully published the first issue and promised a second. It took him a year. (Does this still qualify it as a periodical or annual?) I will categorize it as a pretty damn good publication given its editorial smarts, visual allure and documentary import.

Below we discuss Dummy #2. I hope we’ll see Dummy #3 some time sooner than later. But If he takes he keeps to this schedule I’ll look forward to another interview next Summer.

Dummy is a provocative title for a mag about comics. Why did you name it that?

I guess because I thought it was funny, but there’s another reason. I never planned on Dummy being a publication that people could buy.

When Paul Reubens died in 2023, I wrote about the incredible artists who designed the sets and merchandise for Paul Reubens’ TV show, Pee-wee’s Playhouse, for the online Comics Journal. But I envisioned an expanded version that could be held and flipped through. It was just something I was playing around with and I called it my “dummy” zine—“dummy” being the technical printing term for a magazine mock-up or prototype. I put it together for myself and thought that I would only make that single copy of that first issue.

Eventually other people saw it and wanted copies for themselves, so I printed up 100 of them to offer online. I stuck with the name “Dummy” because it sounded ridiculous, but also because of the double meaning. Before sending it off to the printer, the very last thing I did was drop that “Dummy” logo on the cover, which probably took me all of three minutes to design. Those first 100 copies sold out in a matter of hours, and now there are people wanting to pay a lot of money for the “first printing.” I wish I had more than just one or two of them left. It’s all very weird.

Your second issue is a lollapalooza. Mice, rats, Mickey … Air Pirates. What is the inspiration for this content?

The Air Pirates are fascinating. I first saw copies of Air Pirates Funnies comic books when I was 10 years old. I was at a friend’s house and his older brother had a hidden stash of underground comix in his room and I would sneak in and look through them—long before I should have been looking at such things. When I opened his copy of Air Pirates Funnies #1, I saw that this was not a regular Mickey Mouse comic book. Mickey and Minnie were having sex, drugs were being used, familiar cartoon characters were using dirty words. That set my head spinning, and my interest in the Air Pirates continues to this day. Why would anyone do something as crazy as take on the most litigious company in the world—Walt Disney? It was a fight that no one could possibly win, let alone a gang of penniless underground cartoonists. Dummy #2 explores the reasons why they did what they did.

To get that story, I researched every possible thing I could about the Air Pirates and talked with the surviving members and others at great length. I still think what they did was insane. But it sure was interesting! To me, it was more along the lines with what some of the early punk bands, or Dada artists, were going for; it was almost nihilistic. For some members of the Air Pirates, their ultimate goal was to fail in the most spectacular fashion imaginable. Their ringleader, Dan O’Neill, told me that he wanted to “lose all the way to the Supreme Court.” Part of what they were doing was a political statement—for some of them, the squeaky clean, all-American version of Mickey Mouse of the late 1960s was the symbol of everything that was wrong with the country at that time. They wanted to stick it to “the Man,” and Disney represented “the Man.” Other parts of their fight were deeply personal. It’s a very complicated story.

Of course, artists have been taking shots at Mickey from around the time he was created nearly 100 years ago. The issue also looks at other Mickey parodies—Tijuana Bibles, Wallace Wood’s infamous Disneyland Memorial Orgy poster, MAD magazine’s Mickey Rodent, plus related characters like Robert Armstrong’s Mickey Rat, Kaz’s Creep Rat and more. There’s even an interview with Stanley Mouse, conducted by Edwin “Savage Pencil” Pouncey, that looks at how Ed “Big Daddy” Roth ripped off Mouse when he created Rat Fink. Had time—and space—permitted, I could have included many more examples.

Does your exploration of how the Mickey Mouse trademark has been “abused” have anything to do with it falling out of copyright?

Absolutely. When I was thinking about Issue 2, Mickey Mouse was all over the news because of the 1928 animated short film Steamboat Willie entering the public domain. Some (well, a lot of people) were under the mistaken belief that it meant that anyone was now free to make their own version of Mickey Mouse without fear of legal action from Disney. That, obviously, was not the case. It was Steamboat Willie that entered the public domain, not Mickey Mouse. The things that were created as a result—a horror movie, a bunch of social media parody posts—died out pretty quickly and were nothing compared to the mess the Air Pirates found themselves in (in part, by their own design). I had written about the Air Pirates in the past, but never really anything all that in depth. It seemed like the perfect time to do the deepest possible exploration of their strange story. And I am extremely grateful for the willingness of all the living members (Ted Richards died in 2023) to share their time and archives of art with me. All of them—Dan O’Neill, Bobby London, Gary Hallgren and Shary Flenniken—could not have been more accommodating and helpful. The issue couldn’t exist without those conversations with them, covering things that you’d never find in any of the existing historical documents. It took a long time to complete this issue, but I wanted it to be the last word on the Air Pirates story.

When Air Pirates Funnies appeared, Gary Hallgren and Bobby London were riffing on the history of American comics with a jaundiced underground view. What was the consequence of pirating such holy characters?

Well, for the Air Pirates, the most profound consequences were that they spent almost 10 years in and out of courtrooms, learning an awful lot about copyright and trademark law the hard way. When Disney saw what the Air Pirates were doing–scandalous parodies of their valuable intellectual property–they immediately served legal papers demanding that the group stop publishing materials using their trademarked characters. A large number of the Air Pirates comic books were also confiscated and destroyed, especially Issue #2 of Air Pirates Funnies. Most sane people would have quit at this point, but the Air Pirates didn’t. Some of the members continued to draw Disney characters, and this enraged Disney further. It was a very provocative, and very risky, thing they were doing. It’s pretty bizarre, but Dan O’Neill actually wanted to get in trouble for doing what he did. He got his wish. But this is stuff you can read in a Wiki entry about the Air Pirates. What you won’t find there is an understanding of their motivation—all of them, not just O’Neill’s. Why did they do such an absurd thing? You’ll have to read the issue to find that out.

Dummy is like a museum exhibit on the perils of influence and parody. What is your intention? What do you want the reader to learn from this?

More than anything else, I want Dummy to be a publication that honors the art that was created by these people. To achieve this, Mark Newgarden (Dummy’s consulting editor) advocated the same strategy that he had employed for the stunning book that he did with Paul Karasik, How to Read Nancy: when writing about history, always use the absolute best images possible, directly from the source material. We wanted each image to look like a historical artifact that was right there, lying on the open page. (And the backstories of getting at some of those materials are real detective tales that could easily make up their own issue of Dummy.) So we weren’t going to go to print until everything was just right, which took time, but it was worth it. I also want Dummy to document history for future comics scholars. So there’s an educational goal here as well. Maybe the biggest lesson one can learn is this: Don’t mess with Disney … unless you want to get in trouble. Which is precisely what the Air Pirates, or at least some of them, wanted. What they did was extremely interesting, but it was also absurd. You could say that the most interesting thing about it was how absurd it was.

There had been similar infringements prior to and after Mickey—like Archie in MAD Magazine. How did the comics industry evolve because of it?

Nobody else in comics ever got into the type of legal trouble the Air Pirates did. Their case went all the way to the Supreme Court. Parody has been around forever, at least since the time of the Ancient Greeks. But what the Air Pirates did—it’s hard to even call it parody. In Dummy #2, the illustrator and movie production designer William Stout, who himself parodied Mickey (and instead of getting sued, was paid by Disney to do it!), says that what the Air Pirates were doing wasn’t parody—“it was Mickey Mouse.” Ultimately, as a result of the legal issues around this case, the courts ruled that it was OK to do parody—one time—but that is was not OK to do what the Air Pirates did, which was start up a line of comic books using someone else’s characters. That’s why the case is still studied at law schools today.

What do you think is the most historically revealing in this issue of Dummy?|

That the Air Pirates story involves a lot more than just their leader, Dan O’Neill. Dan is a fascinating character, but so are the other members. Usually when a story about the Air Pirates appears, it only focuses on O’Neill; I wanted to bring the rest of them into focus.

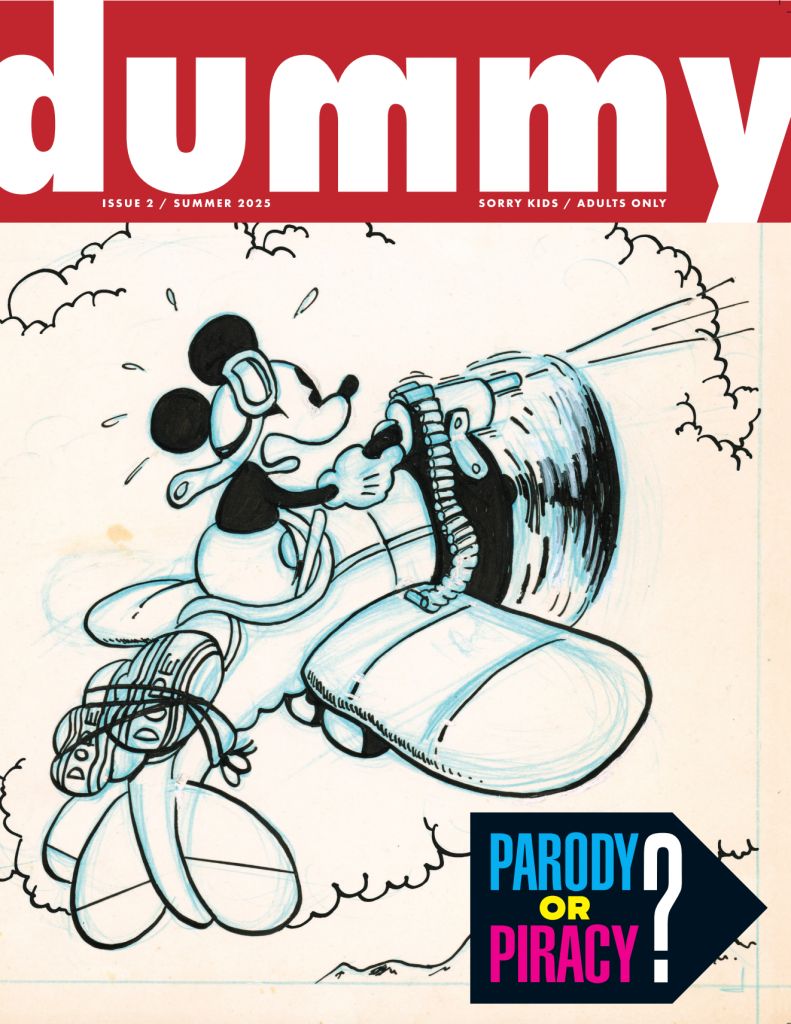

For me, though, the biggest surprise was learning that Bobby London—who drew the original art for the cover of Air Pirates Funnies #1 that I reproduce on the cover of Dummy #2—later got a job working for Disney … drawing Mickey Mouse. The issue also contains a historic, never-published interview from 1972 with the Air Pirates (minus Dan O’Neill) and the underground comix historian Patrick Rosenkranz. That piece captures what they were thinking just before all the legal trouble really became a reality. Disney had served them papers but the worst was yet to come. As far as the images, there’s just a lot of art in the issue that no one, or hardly anyone, has ever seen before. Personal archival material from members of the Air Pirates, photos, a page of business plan notes, legal documents, etc., and all of it is reproduced at the highest quality possible. We really wanted to make it feel like you were going through a file with the documents and artifacts in front of you.

With comics becoming such valuable IP, do you think issues of plagiarism or inspiration have become more or less critical?

I think the territory covered in this issue has never been more important. We live in a time when the work of artists (and writers and all other creators) is being stolen by AI. So the threat of intellectual property theft for artists is a constant battle. And even 50-plus years ago, what the Air Pirates did was not popular among a number of the other underground cartoonists. It wasn’t just Disney who was pissed at them. Nobody wants to see their intellectual property stolen by someone else.

Whats next for Dummy?

I’m going to continue to use my own personal interests to guide what I do with Dummy. Essentially, my target audience is one person: me. I want to make things that I wished existed, things that if I came across them in a store I would be immediately compelled to own. The way my brain works, the only way I truly learn about something is by writing about it. And I can’t write about something unless I put in all the work of researching and talking to the right people about that subject. I have two issues out now and I’m just getting started. There are many other topics to explore and puzzles to solve.

The post The Daily Heller: Of Mice and Memes appeared first on PRINT Magazine.