In conjunction with Poster House’s current exhibition The Future Was Then: The Changing Face of Fascist Italy, I presented a “timely” talk spotlighting the visual ubiquity of the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. Based on my book Iron Fists: Branding the Twentieth Century Totalitarian State, the discussion centered on the continuous barrage of graphic propaganda aimed at malleable children and teens.

The Italian Fascist section of Iron Fists: Branding the Twentieth Century Totalitarian State

The following was a tempting tangential story that I decided to spare the audience …

Benito Mussolini began his political career in the Austro-Hungarian empire as the secretary for a local trade union and a journalist for the Socialist newspaper Il Popolo—which got him deported to Italy. He continued his relationship with the latter, which began to publish his only novel on a serialized basis in 1910.

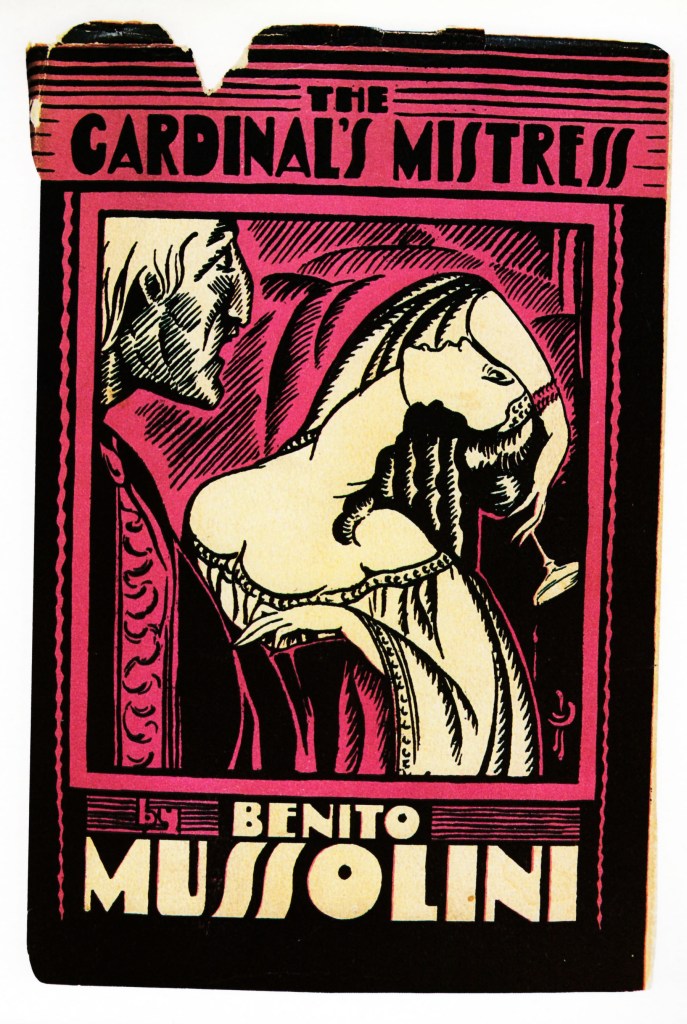

One of his forgotten lesser achievements was a bodice-ripping novel that attacked the Catholic Church titled The Cardinal’s Mistress. Mussolini said he had based the premise on true events, depicting an sordid affair between a 17th-century cardinal of Trent and his mistress, Claudia, the Pope’s niece. The affair becomes known, the Pope intervenes and prohibits the cardinal to marry; without any hope of happiness, the only heir commits suicide, poisoned after spurning the advances of a nefarious nobleman.

This is novel-as-screed, within which Mussolini reveals a long lurid history of Catholic clerics’ lengthy list of secret families, illicit marriages and accusations of homosexuality. It is chock full of scenes depicting self-flagellation, masturbation and fantasies of rape. Released between January and May 1910, it proved to be briefly popular with Italian readers, since Mussolini’s political and journalistic reputation was rapidly rising as a leader of Italy’s Socialist party and editor of its largest Socialist newspaper. He tripled its circulation through savage critiques of imperialism, capitalism and, of course, religion.

The book wasn’t translated into English until 1928. By then, Mussolini had abandoned his radical Socialist ideas for a bombastic, brawny and often violent form of Nationalism. After several years of rising tensions and threats, his Italian Fascists seized power in 1922, and Mussolini became prime minister, establishing totalitarian control of the country.

Despite evidence of Mussolini’s growing suppression of civil liberties, many in the West gave him their tacit approval, lauding his attempts at organizing and modernizing a country that had suffered economic and political unrest in the post–World War I years. But others saw through “Il Duce’s” swagger, including writer and critic Dorothy Parker. Mussolini’s novel had seemingly been forgotten, before being resurrected and translated in 1928, to capitalize on his fame. When Parker reviewed the book under the clever title “Duces Wild” for the Sept. 15, 1928, issue of The New Yorker, she turned her barbs against Duce, slamming its purple prose and scattershot plotting, claiming that despite locking herself in her apartment she could not even force herself to finish the book.

By the time it was published as an English-language edition, Mussolini himself had dismissed the book as “a novel for seamstresses and scandal.” For decades, the church whom Mussolini saw as the enemy, eventually agreed to a pact, known as the Lateran Treaty. Among the concessions the treaty negotiated was recognition of Vatican City as a sovereign nation under control of the Pope, mandatory religious instruction in Italian schools and the outlawing of divorce. One last concession: The Cardinal’s Mistress was removed from bookstore and library shelves and soon faded into obscurity before being rereleased in the 1950s, more than a decade after Mussolini’s execution at the hands of the Italian Resistance.

The post The Daily Heller: Mussolini’s Failed Purple Prose appeared first on PRINT Magazine.