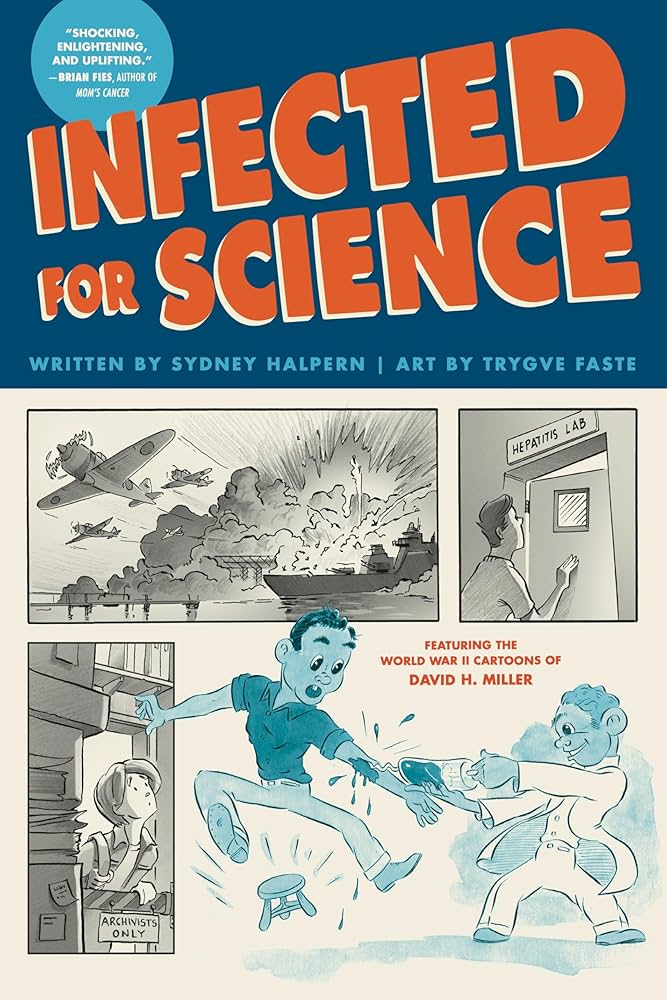

From 1942 through 1972, American biomedical researchers deliberately infected people with hepatitis. Government-sponsored researchers were attempting to discover the basic features of the disease and the viruses causing it, using as research such subjects as conscientious objectors, prison inmates, the mentally ill, among others—including children. Drawing from archival research and in-person interviews, Sydney Halpern, a historical sociologist who has written extensively about 20th-century American medical institutions and biomedical science, uses the graphic novel genre to trace the hepatitis program from its origins in World War II to its demise in the early 1970s.

In addition to the original art in Infected for Science, Halpern has excerpted material from a book of personal cartoons by a research subject named David H. Miller, who chronicled his experience.

I sought to learn why Halpern decided upon the graphic novel format to tell this horrific story. The author and illustrator, Trygve Faste, respond below.

What was the impact of David Miller, the pacifist who is your protagonist—a willing receiver of hepatitis who sketched his experiences?

Halpern: Discovering Miller’s cartoons got me thinking in a new direction. I found the drawings captivating, and I knew they were unique. I was aware of visual imagery showing medical interventions going back to the 19th century. But I had never seen or heard of cartoons depicting medical research created by a human subject. I was eager to find a way to make them widely available.

What was it that put you on the trail of this story?

Halpern: I love historical detection—rummaging through boxes of archival records looking for revelatory documents. This proclivity led me to unearth details of the extensive U.S. hepatitis-research program and to examine how its scientists secured a wide variety of human subjects—not only conscientious objectors (COs) like Miller, but also prison inmates, people with developmental disabilities, and mental patients. Archival material on experiments with the COs is especially abundant, and this allows our account in Infected for Science to be rich and historically grounded.

Your book is an upsetting piece of American history with similar precedents in many other areas of research. Why did you decide to tell the story via graphic novel?

Halpern: Because Miller’s drawings are so compelling and I had already collected a large volume of material on the U.S. program of hepatitis studies, a comic version of the story integrating Miller’s cartoons—and with him as the protagonist—seemed both doable and full of possibilities. [My previous book] Dangerous Medicine is prose-only scholarship, and like most accounts of its kind, it has a limited audience. Trygve and I felt the graphic format would make the history accessible to a broad range of readers. Recent years have seen a growing number of nonfiction comics recounting troubling episodes in U.S. history. Infected for Science is part of this emerging body of graphic narratives addressing challenging real-world subject matter.

Why did you, Trygve, choose the casual drawing style and visual language that you did to tell this story?

Faste: One of the challenges in creating imagery for the book was making art that is compatible with Miller’s cartoons, yet distinct from them. I thought a simplified style worked well for this; it helped make our drawings and his images look like they belonged in the same reality. The simplified style also provided enough contrast with Miller’s that the era and approach would be noticeably different. Another factor was that I didn’t want the artwork to set the wrong tone, to be overly dramatic or otherwise skew the narrative tone of the project. I had fun experimenting with styles in my early concept sketches. It took a while to find the right look, but once I got the level of detail for the story’s main characters just right, it was clear we were on the right track.

For the reader’s knowlege, please explain how the book is structured.

Faste: The story alternates back and forth between two different timeframes: 1945, when the experiments with conscientious objectors took place, and the near-present when the historian, Sydney, finds Miller’s cartoons and locates his adult children, Linda and Jon. As the narrative proceeds, the three near-present-day characters piece together and comment on events taking place decades earlier. Handling these periodic changes in the story’s timeframe without confusing readers was tricky. The book’s chapter breaks—the narrative has a prologue and 12 chapters—helped us signal many of the timeframe shifts.

Were the subjects of these experiments given a real choice?

Halpern: Miller and his fellow research subjects were assignees in Civilian Public Service (CPS), a system of camps where, during World War II, COs performed service alternative to the military draft. Men in CPS had options for the service they performed. Many worked in camps with projects overseen by the government’s forest, soil conservation, or National Park agencies. Other were aides at hospitals or training schools. Those inclined to be subjects in medical research—to participate in what the men called “guinea pig” projects—had to apply for this work and be admitted. The men who volunteered for these projects wanted to assist researchers to better understand diseases afflicting soldiers.

So yes, the COs who were research subjects did have a real choice. But the scientists enrolled other people as subjects who did not freely choose. One of the book’s chapters recounts objections a group of COs raised when they learned researchers were infecting unconsenting mental patients with hepatitis viruses. The CO’s actions were a remarkable episode of research-ethics activism.

Do you feel this work was justified for the greater good?

Halpern: The U.S. armed forces did indeed use unconsenting soldiers as subjects in dangerous experiments—for example, in studies exposing service personnel to chemical agents including mustard gas. But scientists did not enroll soldiers in human-infection studies for fear of disease transmission: Soldiers might later be deployed in locations where they could transmit the disease to military personnel or civilians.

[And] no, we do not believe that deceiving people used as subjects in dangerous medical experiments or enrolling them without consent is justifiable in the name of science or the greater good.

What did you learn from all this research?

Halpern: We learned a great deal about the commitments and beliefs of the COs who are central characters in the book: David the cartoonist; Leonard, one of David’s bunkmates; and Tim, who was assistant director at the hepatitis camp. We learned Miller didn’t talk about experiments, and his family knew little about his participation until, decades later, after his death, his daughter found sketchbooks with the research-subject drawings. We learned about the communal ethos at the CPS unit where the hepatitis studies took place. The young pacifists at the camp were morally centered, altruistic, and wanted to make a difference in the world.

Faste: We leaned into the perspectives and experiences of the story’s characters and set out to convey a difficult history by providing a relatable and personal narrative. Miller’s cartoons, while disturbing, have a large element of dark humor. His personality comes through the drawings and provides a window into how he and his fellow COs kept up their courage and morale during a fraught-filled time for both them and the country. We felt that sharing Miller’s lens on the perilous wartime experiments would be compelling for audiences unfamiliar with this type of material.

What do you want the reader to take away?

Halpern: We would like readers to see the moral complexity in the story. How scientists pursued the goal of better understanding a serious disease was troubling and ethically dubious. The human subjects included members of vulnerable groups; many had not consented. When the studies turned out later to have long-term health consequences for some participants, no agency conducted a long-term follow up study or provided care or compensation. The narrative’s characters point to these and other ethical lapses.

The story also reveals the moral courage of COs who willingly enrolled in dangerous medical experiments because they wanted to help end a bad disease and contribute to the war effort. Who gets to be a hero? We believe it should include little-known people like David Miller and his comrades who had deeply held principles, stood up the vulnerable, and placed themselves in harm’s way for the benefit of others.

The post The Daily Heller: A Graphic Exposé of Human Guinea Pigs for Science appeared first on PRINT Magazine.