I am the product, I am the platform, I am the brand.

Something I have been mulling over recently is this idea that the general public are performing advertising on behalf of brands. I think it was probably off the back of Casey Lewis’ annual What Gen Z are getting for Christmas round-up, where reels after reels of photogenic girlies display their Stanley cups and new UGG Classic Ultra Minis. It got me thinking about how buying the product is no longer the end of the shopping journey; it’s the entry point. The real work happens afterwards, in how ownership is made visible, narrated, and put into circulation.

For most of the past century, consumer culture has been organised around a relatively simple exchange: brands produced meaning, and people buy products to access that meaning. Identity was something you expressed through what you consumed, but the labour of making those identities legible largely sat with brands, not individuals. If you bought certain products, you didn’t have to explain yourself; the brand had already done the semiotic heavy lifting. You’ve got the Beams x Arc’teryx multi-colour Beta jacket? or the Chopova Lowena tartan safety-pin skirt? These kind of products told the world what kind of person you were supposed to be if you owned it. It is pre-packaged meaning.

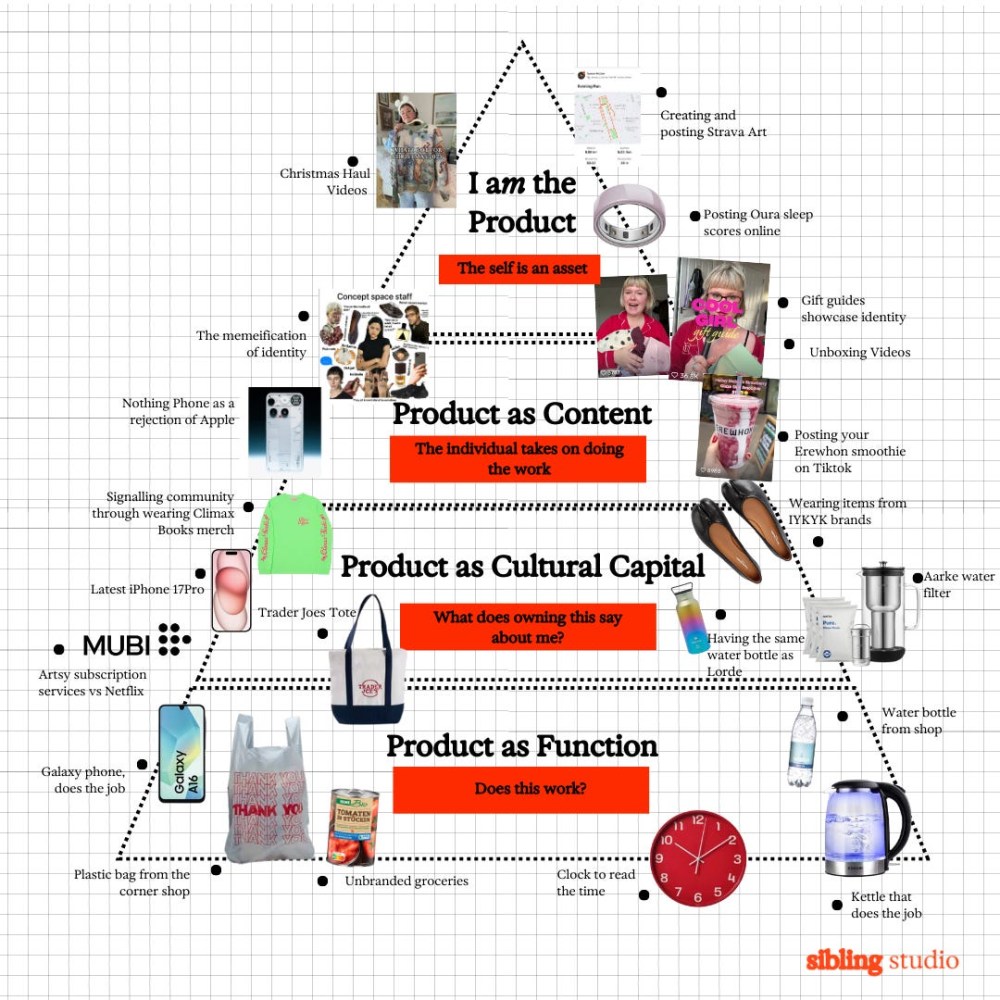

It’s been a minute now since products were bought solely for what they do. Now it’s about what they allow the individual to signal: taste, belonging, discernment, proximity to a certain lifestyle and, crucially, how legible that signal is to others. In this context, function becomes the baseline, not the differentiator. The premium is paid for recognisability within the right social codes. Why buy a €30 Brita water filter when you can place a “timeless,” ergonomic, stainless-steel carafe from Aarke on your kitchen counter for €170, not because it filters water better, but because it places you firmly and undeniably within the creative class.

What we’re starting to see now is not just a change in taste or behaviour, but a quieter economic reorganisation, one where the individual self becomes the primary site of value creation. Ownership is no longer the end point of a transaction but the beginning of a new kind of labour.

The rise of front-facing cameras and platforms like TikTok has turned everyday life into a continuous site of production, where identity is not simply expressed but actively worked on in real time. Ordinary activities like getting dressed, making breakfast, going to the gym, ordering coffee, are performed with an audience in mind (real or imagined). The self becomes the medium through which brands acquire meaning, while individuals, often unintentionally, take on the work brands once did: positioning, differentiation, and proof.

This line of thinking directly echoes the academic Brooke Erin Duffy’s 2017 book (Not) Getting Paid to Do What You Love, which examines at what happens when creativity, identity, and work collapse into the same space. Duffy traces how social platforms have drawn huge numbers of people into posting, sharing, styling, and narrating their lives under the banner of passion and self-expression.

The promise is visibility, connection, maybe even fame or a career. But the reality is more uneven. A small minority actually manage to turn that visibility into income, while most participate as a kind of ongoing side project, producing content, circulating products, and normalising brand presence without ever being paid for it. The labour still happens; it’s just framed as fun rather than work.

The striking (if not surprising) thing is how gendered this dynamic is: most of the people posting are women, and increasingly, girls. Pre-teens and teenagers are filming GRWMs, performing multi-step skincare routines for one another, and speaking fluently in meme language. What looks like play or self-expression often functions as early training in visibility and sales.

The expectation that self-presentation, aesthetic effort, and emotional openness should be offered freely because you love it mirrors much older ideas about whose work counts and whose doesn’t. In that sense, the contemporary “me” economy isn’t entirely new. It follows a familiar pattern: value is generated through people making themselves visible, while the time, effort, and judgement involved in making life look good are rarely recognised as work. Platforms and brands benefit from that visibility, but the labour behind it is framed as personal expression rather than something that deserves to be paid.

What matters, then, is not just the product, but how it is activated through the self — and ultimately, how that self is read in public. Ownership becomes content; content becomes identity; identity becomes an economic asset circulating through platforms designed to extract value from visibility.

Interestingly, this evolution is not linnear. As brands move up the pyramid, abstracting themselves into values, worlds, and cultural posture, individuals are pushed in the opposite direction, down into labour. The work of meaning-making, distribution, and identity signalling increasingly falls on the person rather than the company. Brands become lighter, more conceptual, more removed; people become the infrastructure through which those brands are activated, circulated, and made legible.

Mouthwash Studio’s idea of the “pleb influencer” captures the final stage of this shift. Influence no longer belongs to a visible class of creators; it has been fully normalised as a condition of participation. When everyone can be an influencer, everyday life becomes promotional infrastructure. The distinction between expression and advertising collapses, not because people are trying to sell, but because visibility itself now performs economic work.

Platforms have normalised a way of living where everyday life is quietly organised around being watchable. Bedrooms become sets, bathrooms become studios, private routines become content addressed to an imagined audience. The effect can feel faintly dystopian; a distributed Truman Show, in which people are advertising products, habits, and lifestyles to unseen cameras, without ever being cast or paid.

Visibility becomes ambient rather than exceptional, and performance less a choice than a default condition.

As visibility becomes more extractive and performance more ambient, some of the most meaningful forms of identity and belonging are quietly moving out of view; into smaller, slower, less legible and harder to reach spaces. Offline communities, finstas, private chats, niche scenes, and unmonetised and unreachable spaces.

This doesn’t signal an end to the brandification of the self, but a growing desire to reclaim parts of the self that don’t need to be performed, optimised, or read. Not everything is meant to circulate. And increasingly, that is kind of the point.

Lucinda Bounsall is a Strategy Director and Founder of London-based, Sibling Studio where her team provides brands with strategy that’s culturally attuned, commercially sharp, and actually works for how brand teams operate today. This essay was originally published in Lucinda’s Substack channel.

The post From Consuming the Product to Becoming the Product appeared first on PRINT Magazine.