Years ago, I picked up my mother from the train station; she was coming to Connecticut from Manhattan for a short visit. It was back when she was able to get around easily and by herself, which she is no longer able to do. When she settled down next to me in the passenger seat of my car, I noticed on her left hand a new diamond and gold ring with a horseshoe charm hanging off it; she flicked at it with her right index finger so that it jangled and spun, , and distracted her for the rest of the ride to my house. I had never seen the ring before. Susan and I had been supporting her while struggling ourselves, and I wanted to know: had she spent her food money on jewelry? I could see the veins on her neck start to bulge in fury. How dare I ask such a question.

No, she said — Loretta bought it for me.

Loretta was a longtime friend with whom she was constantly at war.

Do you expect me to believe that Loretta bought you a gold and diamond ring?

My mother changed the subject, but she had made it her truth: that her friend had bought her this ring. (Which, I should be clear, is not completely farfetched: if I see something that I think a close friend will love, I will often buy it for them, and hang onto it until Christmas or their birthday rolls around. But this was not Loretta’s way, and they’d never had that kind of relationship.)

A few months later, I arrived at her apartment to take her out to lunch, and noticed that her cheekbone was lightly bruised. When I asked her what happened, she said I walked into a wall. Weeks later, a bill arrived for a round of Botox, administered by her dermatologist.

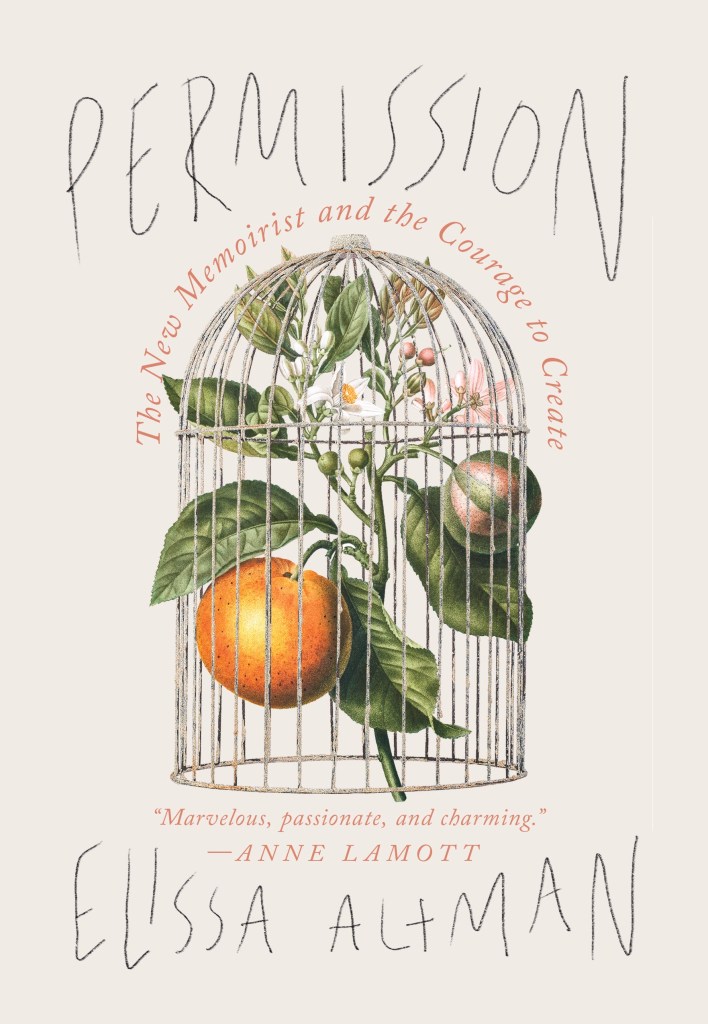

As I wrote in Permission, the vagaries of truth-ownership stem from the fact that each of us tells our stories through the scrim of our own experience.

My mother is now 89 years old, incapable of walking unassisted, incapable of doing her own laundry, going grocery shopping, or getting in and out of an Uber without the help of three people. A few weeks ago, I picked her up in New York to take her to a dental appointment in Connecticut. When I called her from the car to let her know I was close, she said that I was rushing her, and because I was rushing her, she fell. She repeated this on her way downstairs in the elevator, and told the doorman: she was rushing me, and I fell. So I asked the appropriate question: Do you want me to call an ambulance, just to get you checked out? She flushed a deep red.

I was lying, she admitted.

Why—?

Because I wanted you to feel bad about yourself, she said.

They say that with age comes the loss of filter, which has never really been a problem for my mother. But lying about falling is a whole other can of worms, especially because she does fall — a lot — and her building keeps a record of whenever it happens, with days and dates. It reminds me of that scene in Motherland, when, after a catastrophic fall resulting in an exploded ankle, a titanium plate, and seventy-five screws, the city sends over nurse examiners from every part of the Department of Health, and she tells one of them I have something to share with you: My daughter hit me. A social worker, a nurse practitioner, her aide, and an insurance examiner all leaned down to my mother to ask: Is that really true? Because those are extremely dangerous allegations to make, especially against your daughter.

She laughed. Of COURSE it’s not true, she said. I just wanted to see if you were paying attention.

(At that point in the book, I become faint, and my mother’s aide sits me down with a cool, damp washcloth and wraps it around the back of my neck.)

Lying has always been my mother’s norm, her default. I remember when I was a young child, lies were just always there. She lied about my father, stepfather, her bosses, and me. She lied about her credit card. She lied about her in-laws. After Covid, when she moved back to New York in June 2020, she demanded that I give her money to replenish her stock of Clinique lipstick, which had dwindled from thirty-one tubes down to half that amount. I said no, that fifteen tubes would be more than sufficient to get her through at least the next six months. In a rage, she called the bank and filed a complaint, leaving out the part about the lipstick; they asked her whether or not she felt endangered because I was withholding life essentials from her. She said yes, and they called APS, who launched a three-month-long financial investigation of me. By the end of month two, it was obvious that it was a frivolous claim involving lipstick — she admitted it to them — and they closed the case. Two months later, I had a stroke.

Children believe our parents’ lies because somehow, somewhere, we need to believe them. Is it any different for adults?

Other lies I grew up with: that my father had owned an Aston-Martin when he was a bachelor. (He had never owned a car until he moved to Canada for three years, and it was a Buick.) That we were closely related to Barry Goldwater. (We were, but only very distantly, thank God.) That we were closely related to Robert Altman. (We are, more closely than to Barry, but still only very distantly.) That under New York City law, my father owned my grandmother’s Brooklyn apartment in perpetuity, as son of the original renters who had been in the building since 1934; it was a rental, and although I was his daughter and I was living there without him, it was considered an illegal sublet, and I was being evicted by the landlord. (I left before that happened.) That my great-uncle was institutionalized because he had been hit in the head with a baseball in 1942, and it changed his mood; he was institutionalized because he was, according to city death records, a schizophrenic, had developed syphilis, and died in 1944 while still in-patient. That it was my grandfather who had walked out on my father and aunt in 1926 as opposed to my grandmother, because mothers don’t leave; she came back after four years, not three. (Census records on Ancestry.com proved the claim false.)

One of my all-time favorite books, and one that I teach in many/most of my memoir classes, is The Duke of Deception by Geoffrey Wolff, which is entirely built upon a father’s lies to his son, and pretty much anyone who ever crossed his path. The core thread: children believe our parents’ lies because somehow, somewhere, we need to believe them. Is it any different for adults?

Other, bigger lies: The Gulf of Tonkin Incident in 1964, the result of which was the escalation of the Vietnam War, which killed 58,000 American soldiers and 3.8 million Vietnamese. Saddam Hussein’s Foreign Minister, Muhammad Saeed Al-Sahhaf, aka Baghdad Bob, who, on live television, claimed that Baghdad was not being attacked and that all was well, as bombs exploded behind him, and was shown on a live feed. What else: the Nazi claim that Jews have flat heads, which was a core part of the Nazi propaganda machine, to the degree that “scientific” films were created to prove it to the public, who bought it. There’s that little Weapons of Mass Destruction fib. I could go on and on and on, and likely, so could you, especially now, when perfectly reasonable people are buying daily political and nationalistic lies that cause them to not believe their own eyes. It worked in 1942, didn’t it? Yes, it did. It worked when we were told that Covid didn’t exist, despite 1.1 million Americans dying from it. We should be far less afraid of the lies themselves than the fact that people — ordinary citizens, golfing buddies of yours, maybe your kids’ soccer coach or your doctor—are falling for them hook, line, and sinker.

Do the roots of the story come from a place of psychopathology, fear, shame, or desperation? Is this where all lying comes from?

But back to the mundane stuff. There are obvious moral and ethical problems involving the act of lying; we all know this. Is it just human nature to say things like I really can’t meet you today, I have to have a tooth pulled when you just don’t want to have a meeting with That Person Who Drives You Crazy? Is it just human nature to break a longstanding dinner date with an old friend, citing a stomach bug when, in fact, something better came along? I once knew someone who lied to their boss about getting another job offer as a way to leverage their value in the company they were working for; it was a risk they could (literally) afford to take, and it worked. There was no other actual job offer, but their boss believed there was: my colleague got a significant raise and title change. Lying is also a foundational part of addiction, and it takes everyone prisoner: bottles are hidden in toilet tanks, pills are crushed and packed into empty capsules. An end-stage alcoholic person I once knew turned his family inside out to the degree that, rather than deal with his illness during holiday gatherings, they just poured Welch’s grape juice on ice into a wine glass, topped it with a drop of fizzy water, and presented it to him as Lambrusco, and he believed it. That was the holiday when my wife and I hid expensive Gevrey-Chambertin in the basement so that we could avail ourselves of the good stuff while pretending to drink the Gallo. More lies. The dog ate my homework.

Political lying during election season is by no means new, and (sorry, far left and far right), every politician does it, on both sides. But currently, we are being shown what separates a run-of-the-mill liar/fibber/bullshit artist at work from a dangerous ethical deviant: he-who-will-not-be-named promised not to cut Medicaid, and hung his election hat on it. Medicaid is now being cut, and millions, including my 89-year-old mother, will likely die as a result. When questioned about it? He downshifts into what is called the DARVO Tactic: Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender. Deny the initial accusation, attack the accuser’s credibility or motives, and claim he is the true victim. What’s even more dangerous? When he answers So what. Translation: I really don’t care. Nobody cares. Do u?

Regardless of the content of the orange one’s lies, it is their sheer volume that has catapulted the act of lying from something shameful and (ironically, given the number who do it who claim to be Christian) biblically reprehensible (John 8:44 describes the devil as a liar; Revelation 21:8 lists liars as those who will not find eternal life; Exodus says it’s a very, very bad idea) to merely a fact of human life, and a way to possibly succeed at whatever needs succeeding at. Meaning: it’s so trendy right now that it’s become the new black. (Does this mean that orange really is the new black? Sorry.)

In the craft of memoir — of storytelling, both written and oral — the truth must be told.

This past weekend, I was one of millions of readers of The Salt Path who were gobsmacked at the news that much — a LOT — of Raynor Winn’s Odyssean story of doom, healing, and transcendence was, shall we say, “misrepresented.” My first thought: there has to be an explanation. So far, there really hasn’t been one. I don’t know Raynor personally, although we’ve had a few pleasant exchanges over the last few years. I do have a dear friend who is living and declining with CBD (corticobasal degeneration) after a lifetime of excellent health and physical activity, and from what I can tell, it is far more like ALS than Parkinson’s. I also know this: the story, as it has been reported, is wrapped in tales of criminal activity, namely embezzlement and fraud.

Do the roots of the story come from a place of psychopathology, fear, shame, or desperation? Is this where all lying comes from? In the case of The Salt Path, which was published two years before the pandemic and lockdown, a time when so many of us were homebound and longing for signs of relief and the possibility of miracles, does the fact of misrepresentation even matter, given the core of the story: that the couple did hike the SWCP — a treacherous walk according to two dear friends of mine who have done it — and somehow found transcendence as a result?

It does matter. Because, in the craft of memoir — of storytelling, both written and oral — the truth must be told. As I wrote in Permission, and as I have taught and spoken about publicly, truth-ownership stems from the fact that each of us tells our stories through the scrim of experience: put five adult siblings around a table and ask them what happened at Christmas in 1975 when Daddy got drunk on the Jim Beam, and you will get five different versions, including one who will say that Daddy never drank. Each one of these siblings will mud-wrestle with each other to claim the truth, often fighting to the point of estrangement in the name of I’m right and you’re wrong. And each one of these truths is viable. However, there can be only one empirical fact.

Empirical facts: My father never owned an Aston-Martin. We did not own our Brooklyn apartment in perpetuity. My mother’s best friend did not give her a diamond ring. Jews do not have flat heads. I broke a lunch date last year not because I was ill, but because my dining partner had badmouthed me to an entire village of our colleagues, and it had gotten back to me in sordid detail. My great-uncle was institutionalized not because he was hit in the head with a baseball in 1942, but because he was a schizophrenic. Medicaid was cut after we were told it never would be, by someone who has said outright that he does not care. Raynor Winn might indeed have experienced personal transcendence after walking the Southwest Coast Path, but she and her husband were not homeless: they owned property in France at the time of their eviction.

Perhaps it is true that the longer a lie is told, the more people will believe it and the more real it will seem. I remain doubtful that in the case of The Salt Path, something will be explainable, but of course, I don’t know. I tend to think that Winn’s story has more to do with issues of hope, what we want to believe, and why. Guardian columnist Gaby Hinsliff says it best:

“The Salt Path’s reassuring hook wasn’t just the idea of overcoming seemingly impossible adversity, but of how the Winns/Walkers did it – thanks supposedly to the healing powers of nature, the kindness of people who took pity on them and ultimately a book-buying community who helped them spin disaster into box-office gold.

Perhaps it rang particularly true in the aftermath of a pandemic, when many people found solace in both long lonely walks and in the idea that even when terribly isolated they could still be part of something bigger. But for whatever reason, the story met an all-consuming need for hope. Don’t be surprised if the market for journeys of self-discovery endures, no matter what is found at the end of this one.“

This post was originally published on Elissa Altman’s blog, Poor Man’s Feast, the James Beard Award-winning journal about the intersection of food, spirit, and the families that drive you crazy. Read more on her Substack, or keep up with her archives here.

Header image by Joshua Hoehne on Unsplash.

The post Poor Man’s Feast: Is Lying the New Black? appeared first on PRINT Magazine.