I have been thinking about this for a long time and peeling it like an onion, trying to get to its core, and it’s time for me to put it on the table:

I’ve recently had this very tentative conversation with a lot of writers and creatives — on tour, during a weekend workshop I just led at Kripalu, in many private and hushed chats— who have whispered: You too?

The answer is Yes: me too.

As with most complicated things, I have to know what I think — or what I think I think — before I write about them. This phenomenon has touched so much of my life that I can’t ignore it any longer, showing up in my tangled relationship between art-making, permission, sustenance, and alcohol consumption; in my chronic, on-repeat attraction to beautiful, untrustworthy souls who are far too dangerous to cross; in the acknowledgment that, at my age, I will never suddenly become one of the Cool Girl Writers, springing forth from beneath my somewhat dowdy, stress alopecia-addled, bespeckled veneer of shyness and insecurity like Superman coming out of the phonebooth. (As my father used to say, Ain’t never gonna happen.)

I will get to all of those things. But for now, I want to talk about this: the terror of keeping a journal, which leads to what I call EJS, or Empty Journal Syndrome.

Everywhere we look, people are keeping journals, so much so that they regularly trend on social media. A few years ago, Bullet Journals were popular, and I tried to keep one because I thought that, as a creative, I was supposed to; the amount of time it took to organize it was staggering and I managed to fill two pages. There are visual journals, which I am forever seduced by, like Orhan Pamuk’s Memories of Distant Mountains; it flew so far under the radar when it came out in 2024 that many/most of his fans weren’t even aware of it. Or here, on Substack, like

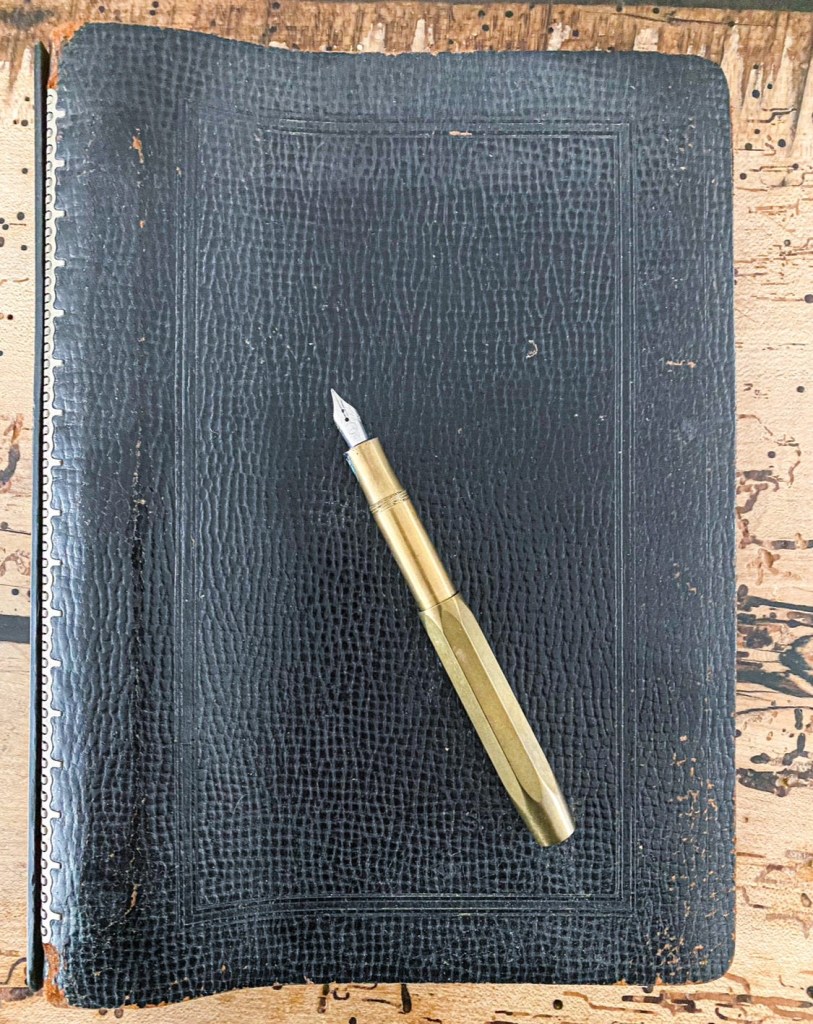

Helen C Stark‘s watercolor journals. Or, famously, Leonardo Da Vinci’s Notebooks, which, when they are on exhibit, I would much rather see than his finished work. Field books have made a comeback and very often, people who keep them don’t even know they’re doing it because they’re unaware of their history; I fell in love with them at the Yale University Center for British Art, at an exhibit called Of Green Leaf, Bird, and Flower, which I wrote about here. (Take a notebook with you out on a hike, fill it with observations and sketches and perhaps a fallen leaf, and you’ve got a field book.) There are process journals, like those of Annie Truitt and Ruth Ozeki (I keep one in my father’s childhood leather school notebook from the early 1930s), and hybrid journals, like Joan Didion’s, whose estate, as of this morning, is selling six of her blank notebooks for $3300. There are fashion journals and food journals; I once knew someone who kept a daily sex journal. (God bless.)

My father’s childhood school notebook is now my process journal.

I recently gave up on my digital calendars — very often they don’t talk to each other, or an appointment shows up in one place and then disappears — and have returned to pen and paper. Over the years, I have kept a Filofax (I have two, both bought in England, one in 1983 and the other in 1985, at Heffer’s in Cambridge). I tried Moleskine calendars but they didn’t work for me because I didn’t love the paper (I’m that person, married to an interior book designer).

My analog datebooks, from Paper Republic.

My current databook/journal of choice is from Paper Republic in Vienna, and I keep both a small one and a larger one, the latter of which lives on my desk, and I love and use them both. They each contain an annual calendar and a separate lay-flat journal insert made from lovely paper; the former is a packed mess, and the latter — the journal insert — is mostly blank. And so are half a dozen other journals that I have scattered around my office: leather-bound ones filled with fancy handmade paper, cheap black and white hardcover school notebooks, (yes) Moleskines and Leuchtturm 1917s, Rhodias and Hobonichi Techos, Romeos and Itoyas and MD Notebooks. For the most part, they are empty except for a few scrawled pages here and there. The only ones that are filled are the journals I kept from middle school into high school and then in the early nineties: they are book-covered lab notebooks, sketchbooks, and green hardback accounting registers. An anomaly: a disintegrating Moleskine from 2013-2015, where all of my notes from various writer’s residencies and silent retreats reside, from Tin House to three-day silent Insight Meditation sits with Sharon Salzberg and Sylvia Boorstein, to a truncated silent sit with the Zen Center for Contemplative Care in New York. I do keep a commonplace book and have for years, but that’s a different story because the words within it are not mine.

The terror of journaling has nothing to do with whether someone else is going to find it and read it.

During a recent book event for Permission, an attendee raised their hand and wanted to talk about journaling both as a creative practice and an act of defiance, joy, agency, and permission, and they wanted to know what I thought. I told them my teacherly truth: that for someone engaged in art-making (which includes storytelling, both written and visual, and even musical), journals allow us to excavate that which does not yet belong on the public page. It is there where we can deride the mundanities of our lives; we can let our egos run roughshod; we can express our fears; we can experiment with versions of things that we’ve written in different tenses and from different points of view; we can blather on about frenemies literary and not; we can tell the story of The Thing That Happened, and revisit it again and again.

The last bit: this is where things begin to get murky.

When I was writing Motherland, I used my 1976-1979 journal for corroboration. I never intended to — I was thirteen when I started keeping it, and in its early pages, it’s filled with a lot of scribblings in colorful magic marker, and many peace signs, daisies, hearts, and Mirabai Bush rainbow stickers. Eventually, there are some boys’ names mentioned, and a year later, some girls’. But in Motherland, there is a scene that takes place in 1979, in which the narrator, sixteen-year-old me, is in her bedroom when her mother barges in to borrow her daughter’s tennis shorts. It’s a set-up: the mother will never fit into the narrator’s shorts because the former is long-limbed, svelte, tall, a size two, and the latter is muscular, square, petite, a field hockey player, and larger than her mother. The mother demands the shorts; the daughter balks. They fight; the daughter knows this is an excuse for her mother to comment on her body. The mother demands the shorts again and threatens to commit suicide if she doesn’t get them. The daughter finally gives in, the mother goes into her bedroom and puts them on, comes back into her daughter’s bedroom, poses in front of the mirror while grabbing a handful of waistband, and wants to know When did you get so big?

It makes me cringe even now. But did this really happen the way I remembered it? Did something so completely outlandish really unfold this way? I wrote Motherland in the days immediately pre-Covid when I was in my mid-fifties, and many years have passed since that day-of-the-shorts in 1979. The filter through which I told the story of the mother and daughter was smudged with time and experience, both of which color memory. I took my journal from 1976-1979 off the bookshelf in my office and read every entry until I reached the one that said, in smeared blue Bic pen: Mom. Suicide. Shorts.

I was right. My memory was accurate. It also meant that my journal from 1976-1979 was kept close, as they all are, as opposed to being buried in a closet or locked up in a safe.

Shortly after my corroboration, I decided to read through all of my journals. The jury is out on doing this — some writers do it, and some warn against it — but there were certain things I was looking for, and what I found was this: entries about some of the most traumatic things that had happened to me in my life, then or now, are nowhere in evidence. My parents’ divorce, which was horrific at best, was missing. Being served divorce papers at fifteen by my paternal uncle because I answered the door instead of my mother that morning in 1978: nowhere. Sexual trauma at the hands of a highly respected neighborhood math teacher, which went on for years: nowhere. Being directly affected by the Son of Sam murders — they happened in my local neighborhood: nothing. Virginity loss: nothing. Severe, incomprehensible bullying from 1977-1978: not a word. Teenage suicide attempt: nothing. An admission — even a remote hint that maybe I preferred girls? It didn’t appear in any of my journals until 1993 when I turned thirty, and shows up with one word: Oh.

Blank journals are representations of negative space, like the sky in a Wyeth painting, that force us to look not only at what is there in our lives, but what isn’t.

Fast forward to more recent journal-keeping: in them, I write about what I’m cooking, what music I’m listening to, which guitar I’m playing the most, what I’m reading, mundane work-related issues, quotes from favorite books, observations about politics, fears about getting older. What does not show up: the wedding at which I was formally excised from my family by a (now) estranged cousin who said We don’t love you anymore; the loss of my father in a car accident; the trials of being an eldercare-giver; paralyzing terror at my wife’s melanoma diagnosis a few years ago; dangerous financial problems; being plagiarized; being ghosted; the frenemy who will just not stop and whose hands I play into every single time; the text exchange with a colleague whose work I loved that included a comment on my heritage of the sort that eighty years ago spawned the murder of my great-grandmother in the forest outside her village in Ukraine; the shock at being hated by people who don’t even know me or what I stand for; the visceral fear of state-sanctioned inhumanity and cruelty.

Can your journal be your best friend? Your confidante and secret keeper and repository for that which cannot ever be repeated? Can it be a therapeutic tool? Of course. But here is an issue that repeatedly crops up in the practice of journal-keeping, but is rarely elucidated: it can also be absolutely terrifying to keep one. At worst, it can retraumatize. It can make The Thing That Happened unequivocally real — there it is, in black and white, in your handwriting — whereas when it lives in your head, it gets caught behind a scrim of time and experience and external modulation. Put it down in a journal and that scrim is lifted, even if you are positive that the journal will never be read by anyone but you, and will be burned to ash in accordance with your last wishes.

In this case, the terror of journaling has nothing to do with whether someone else is going to find it and read it; it has everything to do with immediacy and the vital, living connection between the you who is holding the pen, and the you who appears experientially on the page. You are the same. And because of this, many of us — myself included — have stacks of blank journals representing times in our lives and experiences we’ve lived through that are ineffable and simply too hard to render, even for our own eyes and in a manner devoid of literary performance: if we put it on the page, it is happening, again.

I am reminded of the beginning of Terry Tempest Williams’ breathtaking When Women Were Birds, where she discovers that her beloved late mother’s journals — it is part of Mormon tradition that mothers leave behind their journals to their daughters — are blank.

The journals teach me how nothing is as it appears, writes Williams. An empty page can be full.

I struggle to remember this: journals are repositories of experience, hope, joy, and worry both spoken and silent. They are evidence of life and possibility even when blank, and fear is very much a part of that evidence. Blank journals are representations of negative space, like the sky in a Wyeth painting, that force us to look not only at what is there in our lives but what isn’t; both the seen and the unseen are privately, quietly, revelatory. Don’t fall into the trap of self-loathing when it comes to your stack of blank journals that you bought with the best of intentions: instead, treasure them and know that every empty page tells a story.

This post was originally published on Elissa Altman’s blog Poor Man’s Feast, The James Beard Award-winning journal about the intersection of food, spirit, and the families that drive you crazy. Read more on her Substack, or keep up with her archives here.

Photos courtesy of the author.

The post Poor Man’s Feast: The Quiet Terror of Keeping a Journal appeared first on PRINT Magazine.