When the term vernacular design was arguably introduced in the USA as both practice and style by Tibor Kalman in the late 1980s, it was meant as a critique of slick and formulaic work. To be vernacular implied untrained. Another contrasting factor was vernacular as the everyday techniques and typographics that could be found on Chinese takeout menus as opposed to the polished typography of an annual report, for instance. Vernacular was related to folk art, which suggested an inferior status. Ultimately, the naif was adopted by the professional and, as happened throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries, vernacular became a fashionable design appropriation.

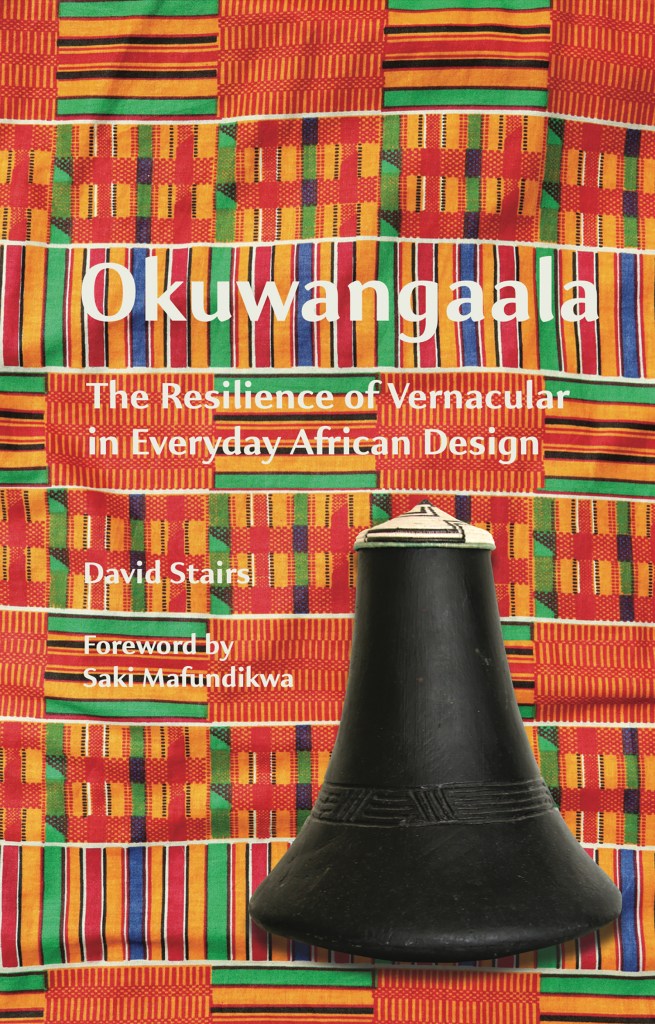

Appropriation at its best is veneration of the authentic and has negative connotations. But it is also a way to describe arts and crafts that emerged from specific cultural wellsprings. In Okuwangaala: The Resilience of Vernacular in Everyday African Design, author, designer and educator David Stairs assembles functional objects, from painted signs to handmade tools and beyond, as a chronicle of Africa’s widespread design cultures.

A teacher at Central Michigan University, he has developed strong links to Africa and its people. Here, he talks about how this little gem of a book came to be.

What precipitated seeking and recording African vernacular design?

In 2000 I won a Fulbright to teach and research in Uganda. One of the requirements for my visa was to register with the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, for which I needed a research topic. I’d been astounded by what I was seeing in African open-air markets, where most everyday commerce is conducted, and understood immediately why so many Hollywood movies staged scenes in African bazaars. Based upon the things I was seeing, “vernacular” became a no-brainer for my research theme.

What was your reason for spending so much time in Africa?

I’d been fascinated with Africa since the days of the Biafran Civil War in the late ’60s, and knew I would go there someday if an opportunity arose. It took longer than I thought it would, but after I got an academic appointment, I began researching Fulbright grants to Africa. At the time there were only two dozen grants to all of Africa, with most of them in South Africa. Makerere University in Kampala had the Margaret Trowell School of Art & Design, and was far and away the best option. Once I arrived I knew I was in my place, and I wanted to go back again and again. I even passed up a stateside job offer because I was planning an African return. It was great to be outside the Amero-Techno-Bubble, in such a grounded environment.

In his foreword to your book, Saki Mafundikwa writes about using the term vernacular: “I actually think that ‘African Design’ would have been a good enough title because I think labels like vernacular or folk relegate the design to a lower rank than Western design.” What is your definition of vernacular?

I understand Saki’s aversion to the word as applied to African design, and I agree with him that African design is generally diminished by the Western/Northern Design Establishment. But I also value precision in language, and the word vernacular works very well as a descriptor of the DIY I was looking at. To me, a child of parochial schools in the 1960s, I witnessed the conversion from the Latin Mass to a “vernacular” English service. Ever since, vernacular to me has meant “of the people.” This can suggest “demotic” to some, but I see nothing wrong with that. And in the sense I am trying to convey, of African native “designability,” I consider it a compliment.

Some of the examples you provide do look as though they were made by amateurs, and some by trained people. Is there a middle ground that is both indigenous and corporate?

So, that depends on the example, of course. The Masaai red blanket was purchased in Arusha, Tanzania, and was industrially woven, but is a color the Masaii prefer. Ditto for the wax-print fabrics from Cote d’Ivoire. This was an industry transferred to Africa from Indonesia by the Dutch, as has been pointed out to me by some in the Netherlands. But bolts of such fabric are available everywhere in Africa, reflecting the popular taste for bright colors, and fabricated by local seamstresses and embroiderers for special and everyday usage, thus marrying industrial product to cottage industry application. Things like the footlockers, hurricane lamps, security fences and electric hotplates made by men who were formerly blacksmiths occupy a handicraft middle ground between industrial weaving and toys self-made by children. And some of those toys, made by kids who never had Legos to play with, are amazing!

The work that you spotlight suggests a commercial reason for being. Why did you exclusively focus on one-of-a-kinds?

To answer your question directly, I was not strictly looking for unique objects, but found many. Some of the artifacts came from craft bazaars that sell things for export: a toy jet plane made from recycled materials, for instance. Other things are strictly made for local consumption. I tracked down John Kitutu with the help of Dr. Catherine Gombe, my dean at Kyambogo University. Kitutu’s workshop was at his home, deep in the bush up on Mt. Elgon, which straddles the Kenya/Uganda border. John was a local potter, so he naturally worked in multiples. I was looking for a terracotta charcoal iron Dr. Gombe had told me about, and John was the source. He had five or six of them lined up on the floor of his hut. His irons were popular not only because electricity was scarce, but because they were beautifully made.

To what extent do European principles of design play in African work?

European design principles are certainly taught at African art and design schools, and many of the African faculty members are European-educated. I remember how one of my African graduate students criticized the local music posters for their crude typography. But I also observed poor African kids, likely illiterate, staring at the faces of the performers on these posters in a way that meant they were clearly communicating their message. The things that most fascinated me were seldom a result of European design, unless it occurred by copying or back formation.

Does African vernacular design influence Africans to use certain forms in the same ways that “retro” designers use old typefaces and vintage imagery in the “West”?

I don’t think the concept of “retro” factors into it. There are examples of reverse engineering, like the African-made popcorn poppers I show. But the local forms, say in the Sudanese “tabaga” food cover or the perfectly balanced Banyankole milk bottle, are more classical than retro.

What are you hoping will be the result of this book? Do you see it as a historical record? A catalogue of opportunities for younger designers?

No 180-page book could ever do comprehensive justice to African vernacular. There are over 50 nations in Africa, and I present objects from about 15. Promo copies I’ve circulated have already been cataloged by the Ojai Graphic Design Program Library in LA and the Yale University African Art Library, so I assume young designers will eventually come across the book if motivated. For me it is less a historical record than an acknowledgement of African creativity, a sign of respect to Africans, and a thank you for all Africa continues to bestow on the world. There are only a few times in life where an experience changes you forever. For me, it was Africa.

Okuwangaala is available from Printed Matter in New York.

The post The Daily Heller: An Unofficial Canon of African Design appeared first on PRINT Magazine.