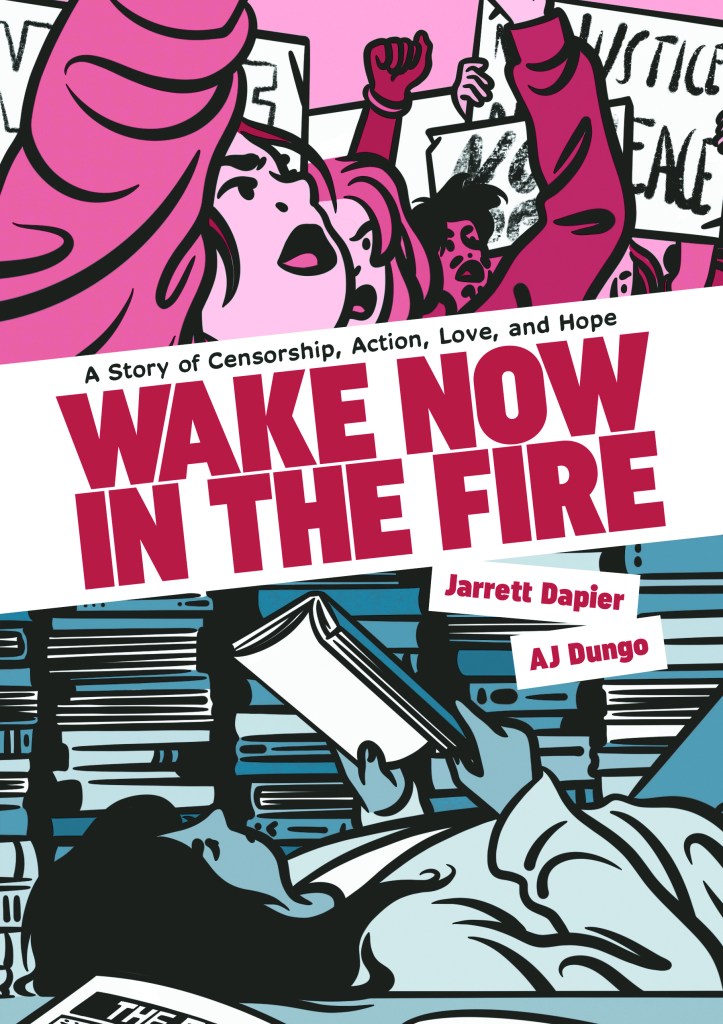

Wake Now in the Fire by Jarrett Dapier is a graphic novel account of the events surrounding the Chicago Public School system’s 2013 decision to ban Marjane Satrapi’s autobiographical Persepolis. With illustrations by comics creator AJ Dungo, Wake Now in the Fire is an inspiring portrayal of student activists taking on one of most urgent issues of our time. Dapier is the Chicago librarian who exposed key information about the censorship decision, which caused a furor. He was awarded the John Phillip Immroth Award from the American Library Association’s Intellectual Freedom Round Table.

It starts as an update at one Chicago high school: copies of a “certain book” are no longer allowed in classrooms or the library. But it’s not just one high school—it’s all Chicago public schools. Not even the principals know why this is happening; they just know they must comply with the order. One thing is clear: The book, which tells a story of oppression, survival and resistance against authoritarian power, is seen as a threat, dangerous enough to ban.

Below, Dapier tell us more.

I don’t usually ask authors to encapsulate their books (that’s my job). But in this case I will make an exception. Please tell us a bit more about the plot and the characters in this very real story.

As the extent of the ban becomes known, the students rise up. They organize a school-wide walkout and library sit-in. They publicize the banning in every forum they can: social media, the press, classes, clubs, the school paper. And most of all, they get everyone they know to read the book: Persepolis, by Marjane Satrapi.

The characters who play a part include:

Aoife, a senior carrying the weight of her dad’s addiction problems on her shoulders at the same time she’s galvanized to fight back against the plan and organize the walk-out and protest with her best friend, Kendall.

Kendall, also a senior, a joyful, goofy and fierce character who understands personally what it’s like to live in a city “that wants to erase her.”

Eli, president of his school’s Banned Books Club, a fierce defender of the first amendment, and excellent mediator.

Aditi, a junior born in Mumbai, India, who is struggling with the feeling that she has succumbed to the hyper-competitive pressures of high school and repressed an important part of herself that cares about books, humanistic values, reading and being a helpful part of her community.

Weston, a senior grieving over the disappearance of his cousin, who suffers from a panic disorder, and may or may not be in love with his actor and artist friend, Miguel.

Xochitl and Jackson: student journalists who show more spine, journalistic integrity and principles than most of what we call the media today.

What reason was given for the banning of Satrapi’s human and illuminating volume?

The CPS school board was never involved. This was a top-down decision from the CEO of Schools at the time, Barbara Byrd-Bennett, to remove all copies of Persepolis from all schools in the system. When the public became aware of the ban, thanks to the students who organized and publicized their protest of it only a few days after the order, Byrd-Bennett insisted she had no knowledge of the directive and insisted it was all a misunderstanding. CPS produced something like eight emails, mostly redacted, between a handful of network managers that worked under the CEO. Those answered nothing about how or why this happened or who really was involved. In 2014, I filed a FOIA request asking for any notes related to a meeting that referred to in one of those emails, and amazingly, I received about 43 pages of emails, which they had claimed didn’t exist. These were almost all redacted, but having worked at the ACLU, I had experience dealing with redactions and I was able to easily lift the redactions off the document (they’d done it incorrectly). I then had the answers to the questions so many people had asked in 2013.

A CPS administrator had found a copy of Persepolis on the shelf in a third grade classroom at a school in the Austin neighborhood on Chicago’s far West side. This administrator then took that copy, scanned the pages in the book that show drawings of a man being tortured in an Iranian prison, and then murdered, and, per the documents I received, wrote a group email to the other network chiefs and Barbara Byrd-Bennett asking if she could remove this book from the classroom in which it was found. Without asking a single question about the book, why it might be in middle school and high school libraries in CPS, why teachers of older students might use it in their curriculum, Byrd-Bennett wrote, “Yes. In fact, let’s remove the book from every single school immediately.” Just dictated it. One person on the chain said “this is part of an approved curriculum for middle and high school…” but Byrd-Bennett ignored that and then demanded to know the name of the person in their literacy curriculum department responsible for adding the title to the approved texts list. It’s wild and also chilling to see how thoughtlessly and imperiously she acted and how easily she could make such a disruptive action occur just on a whim. And then lie so easily to the press and the public when she claimed to have no knowledge of the banning.

How did you decide on the graphic novel as the best platform for this subject?

Once I finished my research and thesis paper about this event (I was in graduate school for library science at the time), I kept feeling like I wanted to do more with the story. There were so many fascinating details, surprising connections and courageous characters to the story, I didn’t want to stop working on it. Ben Joravsky at the Chicago Reader had published my research to expose CPS’ lies about it, I’d been invited by the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund to speak at C2E2, and the more I told the story, the more I saw how meaningful and relevant it was to the issues of censorship, students’ rights, libraries, and more. In spring of 2015 I was taking a class on comics readers advisory taught by my friend Dr. Carol Tilly, and during one of those classes, Carol had brought out a vast selection of every imaginable kind of comic book and graphic novel from her collection to browse and read. Our discussions about those books she had laid out for whatever reason flicked a light on in my head: “I could write a graphic novel about the banning of a graphic novel!” I remember during our break during class, I approached Carol and told her my idea. She took a moment to think about it and then, deadpan, replied, “That could work.” I then spent the next 10 years working on it.

Have there been any threats to ban your book?

No. But, I wouldn’t be surprised if there are soon.

How many people actually support banning books?

Very few. The Washington Post reported in 2023 that the vast majority of the thousands of book challenges that had been filed in the United States since 2020 were filed by just 11 people! But school and library boards have been overtaken by anti-library, anti-literacy, often white supremacist, homophobic ideologues with very strict ideas about what children and teens should have access to read and learn about the world. And those who file the complaints are often well-organized, loud, shameless, and well-funded by conservative PACs. Now state governors and legislators are even getting involved in hyperlocal issues to do things like dissolving library boards they don’t like, usually boards who trust their professional staff, don’t censor materials carefully selected by that staff, and who support the public’s freedom to read. What’s being done is deeply un-American, anti-democratic, and damaging to communities.

The good news is, once anti-censorship folks speak up and organize, they find allies within the community quickly and are often able to rid their school and library boards of these destructive people. It’s a reminder to all of us that we have to practice and defend democracy and our first amendment rights. It takes work.

What are the other “calls to action”?

There are so few libraries or school librarians left in the public school systems in New York City and Chicago, it’s beyond alarming. If you’re in either of those cities or another major city where your school board has attempted to balance its books [by removing] libraries and librarian jobs from schools, cry foul and do it loudly. The children of your cities deserve a quality education that nurtures a life of learning, and libraries are indispensable to that goal. Defend your teens from any forces at school, home, and in the culture that would silence them through shame, punishment and censorship. Support teen-led organizing efforts to combat censorship in every way you can.

But, really, if you want to know what to do, read journalist Kelly Jensen at Book Riot. Kelly just published an invaluable list of 60+ small tasks you can do to defend the right to read. This article is a true guide for all of us who want to fight back and win. Print it out and make some of the tasks she lists a regular part of your weekly routine.

Oh, and, one of the items she mentions is “Read the forthcoming graphic novel Wake Now in the Fire: A Graphic Novel by Jarrett Dapier, based on the true story of a group of Chicago high school students working to overturn the school district’s ban on Persepolis.” I hope you will.

The post The Daily Heller: Banning the Right to Read in Chicago (a Novel) appeared first on PRINT Magazine.