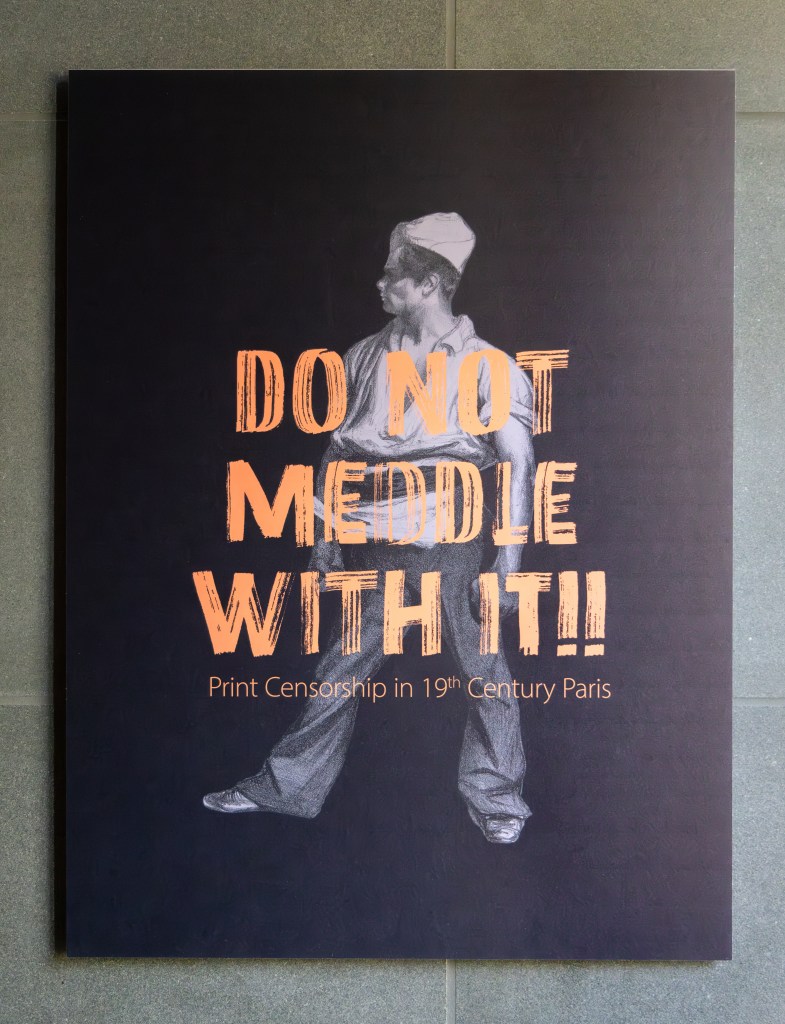

Elizabeth Kathleen Mitchell organized Do Not Meddle With It!! Print Censorship in 19th-Century Paris for the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio. On view through Dec. 7, it’s a timely exhibition with work from the past that informs the present.

Drawn primarily from the McNay’s collection of works on paper, the exhibition features critical images by Honoré Daumier and Édouard Manet in the context of prints made by their peers and later artists. The latter group includes Pablo Picasso, José Clemente Orozco and José Guadalupe Posada, who were inspired by how artists such as Manet and Daumier dealt with government censorship and used caricature to make protest art. In addition, more recent works by activist artists Guerrilla Girls and Donald Moffett add a contemporary lens to the presentation.

As for the title of the show, Daumier’s 1834 lithograph “Ne vous y frottez pas!! Liberté de la presse” (“Do Not Meddle with It!! Freedom of the Press”) captures the spirit of creative resistance in the face of print censorship, in light of the current U.S. administration’s open hostility toward free expression.

Below, Mitchell and I discuss the relevance and goals of this exhibition of historical artifacts in this era’s realignment of the media.

(Header photograph by Jacklyn Velez, courtesy of the McNay Art Museum.)

Is the timing of this exhibition a response to the marked decrease in satiric commentary and art today?

I see political and cultural satire still thriving in art on paper. The exhibition includes more contemporary works by Donald Moffett, the Guerilla Girls and others to demonstrate satire’s endurance. The subject of the exhibition came about when I first surveyed the McNay’s great 19th-century French lithographs. I quickly realized many were affected by—or a direct reaction to—censorship by the government. I started to wonder what the history of prints would look like if these powerful and influential images had never been printed, and built the exhibition around exploring this aspect of art history we rarely discuss in depth.

Édouard Manet, Guerre Civile: Scene de la Commune de Paris, 1871-73. Lithograph. Collection of the McNay Art Museum, gift of the Friends of the McNay.

What are the degrees of censorship that you cover? Government? Industry? And do you focus on governmental and self-censorship?

The exhibition focuses on prints made in Paris between 1820 and 1881, a period during which the state responded to political unrest by clamping down on freedom of the press. France resurrected old laws allowing state censorship of popular and fine art prints for any content critical of the monarchy and government. Censors could request changes, suppress an image, and prosecute the artist, printer, publisher, and even print sellers. Many artists refused to back down, even when facing prison sentences. Some of Honoré Daumier’s most important prints, which are featured in the installation, were intentionally made to raise money for future legal fees and fines.

Honoré Daumier, Ingrate patrie, tu n’auras pas mon oeuvre! … (Ungrateful Country … You Shall Not Have My Masterpiece!) from the series Émotions Parisiennes, 1840. Lithograph. Collection of the McNay Art Museum, gift of the Pan Texas Assembly,

When Daumier was working, the comic/satiric press was the most important outlet for graphic commentary. How does journalism play a role in the exhibition?

Daumier published his sharpest works in periodicals, but different laws regulated censorship of the printed word and the printed image. The government regarded images as being far more dangerous because literacy is not required to understand a picture. Plus, multiple impressions of a single design could reach a wide audience very quickly when they were pasted up on walls or shown in print shop windows around the city. In many ways, prints were the internet of the pre-photographic age. The exhibition includes one lithograph from 1947 by Mexican artist Alfredo Zalce, who took a Daumier-like approach to ridicule unethical journalists who bolster corrupt politicians, but otherwise it focuses on prints.

Norbert Goeneutte, Henri Guérard a sa Presse, or Henri Guérard dans son Atelier, 1888. Etching, aquatint, and roulette. Collection of the McNay Art Museum, museum purchase.

How have artists tackled censorship in innovative ways that are represented in your exhibition?

The installation explores innovative ways artists conveyed information through symbols and also with visual styles ranging from caricature to realism and abstraction. It also looks at how artists engaged with the mechanics of production and commerce to get their message out in the world. For example, the gallery features two vicious satires by Picasso. He made them in Paris in 1937 with the intent of having them reproduced as postcards and sold to fund the opposition to Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, whose regime aggressively censored the arts.

Félix Bracquemond, Le haut d’un battant de porte (The Upper Part of a Barn Door), 1852, printed 1865. Etching and chine-collé. Museum purchase.

Censorship manifests in subtle and overt ways. What in your exhibit covers that range? What had the most negative and positive effects on the culture of graphic commentary?

Because these artists were dealing with the legal front of paranoid and unpopular regimes, the subtlety and creativity largely resided in the artists’ responses. We will never fully know the scope of the biggest negatives: how many brilliant designs were altered or suppressed, and what was the extent of the self-censorship that no doubt occurred. But we can appreciate the rebellious spirits of these smart, brave and incredibly talented artists who defended the free press, and consider their legacies through the 20th-century Mexican, Spanish and American prints included in the exhibition.

Honoré Daumier, Ingrate patrie, tu n’auras pas mon oeuvre! … (Ungrateful Country … You Shall Not Have My Masterpiece!) from the series Émotions Parisiennes, 1840. Lithograph. Collection of the McNay Art Museum, gift of the Pan Texas Assembly.

Do you think that the line(s) between acceptable and not have changed for better or worse since Daumier’s time?

I don’t see a lot of difference because today’s artists and cultural critics target many of the same injustices and hypocrisies they did in Daumier’s time, and in similar ways. What feels different is how photography, a 19th-century invention, and now AI, continue to move the line on what we now believe to be visually “real” or factual.

What do you hope the viewer will take away from the exhibition?

We tend to characterize 19th-century Paris as being a hotbed of expressive new art styles and the exciting public life depicted by the Impressionists. However, that is just one take on a complex story and, as the 20th-century prints in the exhibition show, censorship, oppression and intimidation continue to lurk in society’s shadows.

The post The Daily Heller: Censorship is Censorship, From the Past to the Present appeared first on PRINT Magazine.