Jason Polan (1982–2020) died just as his art star was rising. He had already amassed a niche following with the popularity of his blog Every Person in New York, in which he showed his curiously obsessive passion for drawing and sketching. His eclectic drawings and art projects—including The Every Piece of Art in the Museum of Modern Art Book—made him what The New York Times dubbed “one of the quirkiest and most prolific denizens of the New York art scene.”

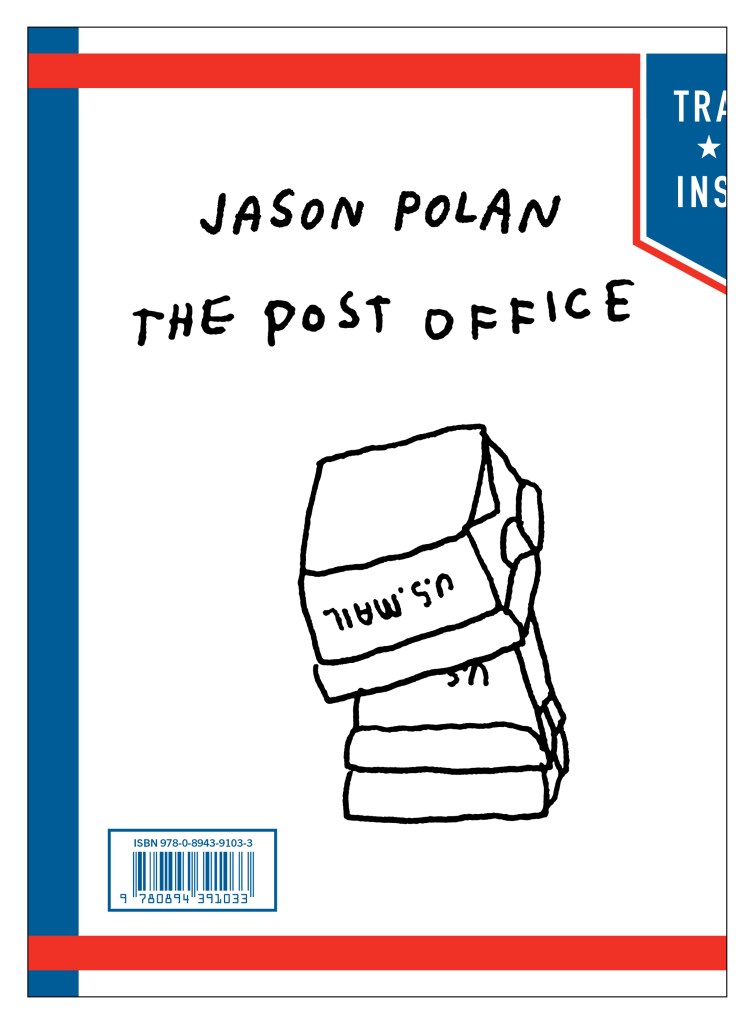

The humble postal label was his preferred way to disseminate his messages, and so was mail itself—so as an ad hoc memorial, postal labels were glued all over New York with messages of love and affection. Now, photographer Jason Fulford, a friend and recipient of Polan’s mail art, has edited The Post Office (Printed Matter), a collection of saved letters, cards and other ephemera from Polan’s fans and friends and the artist too. I was interested to talk to Fulford about how he came to be the official mail sorter—and he obliged with his responses below.

How long were you friends with Jason?

Since 2006. That’s when he first contacted me through the mail.

What qualities in his work do you identify with?

I think we first bonded over a shared love of paper—ephemera, and the excitement of finding something inspiring in a junk store or used bookstore. And then making work of our own, on paper, that had a similar feeling of excitement and potential.

How was Post Office conceived? And did you know that he had saved all this correspondence?

I was invited by Lauri London Freedman to come and look through the boxes that Jason left behind (almost 200 of them). Lauri and a group of Jason’s close friends helped his family sort through everything. When I arrived, in December 2022, the material was pretty well organized—artworks by him and others, books, objects, correspondence, ephemera. I found the boxes of mail that he had saved, and read it all. I was moved to see how many people he corresponded with. And the spirit of the correspondence felt, to me, like a portrait of Jason. It was playful and curious and weird and mundane. It was ephemeral and personal, as if there was an unspoken code between him and each correspondent.

What criteria did you use in selecting material for the book?

I wanted the book to work on its own, visually, and for each spread to give you something, even if you opened directly to that spread without even knowing what the book was about. But then, of course, I also wanted the book to work linearly, and with context, so there is a flow that way as well that tells a story. And we (Lauri, Printed Matter and me) wanted to include a wide range of contributors, so I tried not to use too many pieces by any one person.

Why was Jason so popular?

Well he was popular on two levels—a personal one and a public one. I can only speak to the personal level. He was really great one-on-one—totally game and all in. Up for adventure, and specific to you particularly. I know this from meeting so many of his friends through making this book, and comparing their stories to my experiences. Several people said they would randomly bump into him on the street, and then take a two-hour walk together.

What defines Jason as an artist?

He lived in the moment, and was also ambitious. It’s tempting to connect his premature death and his prolific output, as if he somehow knew and was trying to cram as much life experience in as possible. Of course he couldn’t have known, but it makes you wonder. I felt the same way about my friend Adam Gilders, a brilliant writer from Toronto who died way too young, or the photographer Tracey Baran. I wish I could have seen how all of them would have dealt with the pandemic, or our current situation, or whatever we have in store for us in the coming years …

Do you have more plans for other aspects of Jason’s archive?

I also found a box of his clippings—little things he cut out of magazines and newspapers over the years. I’ve been editing them together into something that might become a book.

The post The Daily Heller: Jason Polan Goes Postal appeared first on PRINT Magazine.