Pablo Delcan, who is among the current wave of high-performance conceptual editorial illustrators, awoke one day to a disquieting question: What is the difference between what he does and AI image generators? “For more than a decade,” he writes in the foreword to his new book, Prompt-Brush 1.0: The First Non-AI Generative Art Model, “my bread and butter has involved receiving manuscripts or drafts for books, newspapers or magazine articles—taking text and transforming it into imagery. It’s a process not so different from the one AI models use to generate images from prompts.”

This set a personal challenge in motion: What if Delcan reversed the process and accepted human prompts? What if he mimicked a bot? How would the result be transformative? So he solicited prompts on social media, which he spun into countless rudimentary drawings. Influenced by the sketches of his son, Rio, he is learning the distinction between man- and machine-made art and its personal levels of complexity and emotion.

Delcan may think he’s impersonating a machine, but he’s essentially testing limits while learning that impersonation is not as simple as turning artificiality on its ear. In this conversation we discuss the levels and degrees of reality that make generative imagery such a paradox for the future of art and artifice.

Your work is, in my view, among the most intelligent conceptual illustration “voices” today. So before addressing your new book, tell me about your Artful Intelligence. Where do you derive influence for your editorial work?

It means a lot to hear that coming from you! I had the great fortune of surrounding myself really early on in my career with mentors that helped me shape this voice. Carin Goldberg was my mentor. I worked for her, I eventually taught with her at SVA and we were close friends; she was absolutely essential to the way I think about process, beauty and design thinking. The second person was Peter Mendelsund, who hired me at Pantheon Books. I learned how to be playful by watching him work and he helped tear down some of my preconceived over-complicated assumptions about how to make good work.

Prompt-Brush is a refreshingly droll way of satirizing the hoopla of caution around AI’s art/antiart potential. What “prompted” you to create this volume?

Prompt-Brush was the culmination of a year where I had to illustrate many articles about the dangers, ethical issues and critiques of AI. I was asked at some point by The Washington Post to make some of the illustrations I had done look more as if they had been generated using AI. That sparked me to think about the opposite question: how can I create work that feels generated by me, a human.

In a way it was less of a critique or activist response and more a real experiment for myself. Using the same formal process that AI employs—receiving input from users, processing that information through Large Language Model (LLM) transformers and getting a quick output—I wanted to see what my equivalent was to that. Fast drawings, no revisions, and sticking with the first idea. Initially I thought I’d spend a day or two receiving prompts from friends on social media and that’d be it. Because of the number of people interested in participating and sending in prompts, it became a bigger and more demanding project than I was expecting.

What are your pros and cons when it comes to generative AI? I mean, do you see a value other than a counterpoint to the tried-and-true art-making techniques?

I’ll start with the cons, because I feel like the positive aspect that I see in AI is in a way a counterbalance to the disruption it’s creating.

The first that comes to mind is that because of AI, the way I was creating work for some time is losing its visual candor. These highly realistic photoshoots of fabricated objects and simple conceptual sculptures have become so easily replicable with these new tools that I’m less enamored with that process and approach. AI continues to become better and better at highly technical, detailed, sleek visuals. So the value of this kind of work feels different than it used to. At least for me.

Another problem I see with AI entering everyone’s toolbox now is how easy it is to create anything—too many things. Too many things. How do you sift through the oversaturation of content when you can’t decipher what is artificial and what isn’t, and at what point will we stop to care?

I’ve been an early adopter of AI; early in 2021 I was experimenting with printing large AI-generated portraits and painting over them. I’ve used it to help me program simple fun video games to play with my kids. I’ve created my own drawing software with the help of AI coding. The pros for me have been to expand what I’m capable of making.

But it is also helping me evolve and try to figure out the kind of work I want to be creating in a future where AI becomes a default tool for image-making.

I was recently watching the 2017 documentary AlphaGo, where the AI lab DeepMind trains a model that defeats one of the best Go masters by making moves that no human would have thought to make before. Lee Sedol, the player, speaks after being defeated by AI, about how this experience made him a better Go player. I’m trying to figure out, how can AI make me better at what I do? I don’t think the answer is necessarily to use more AI in my process, but to see the work we make in this new context and create a body of work that is a reaction or a truly human response to it.

AI output is so speedy. How long did it take you to make the responses to the prompts?

I wanted my process to be as similar to AI as possible, so I try to spend the least amount of time with these drawings. Most of them take less than a minute to draw, some of them two minutes if they are more complex. All the prompts are submitted by people through Prompt-Brush.com. I’ve illustrated around 1,700 prompts so far. I continue to draw every day, and continue to receive new prompts every day. I’m far from completing all of them. I have an Excel file with over 7,800 prompts still waiting.

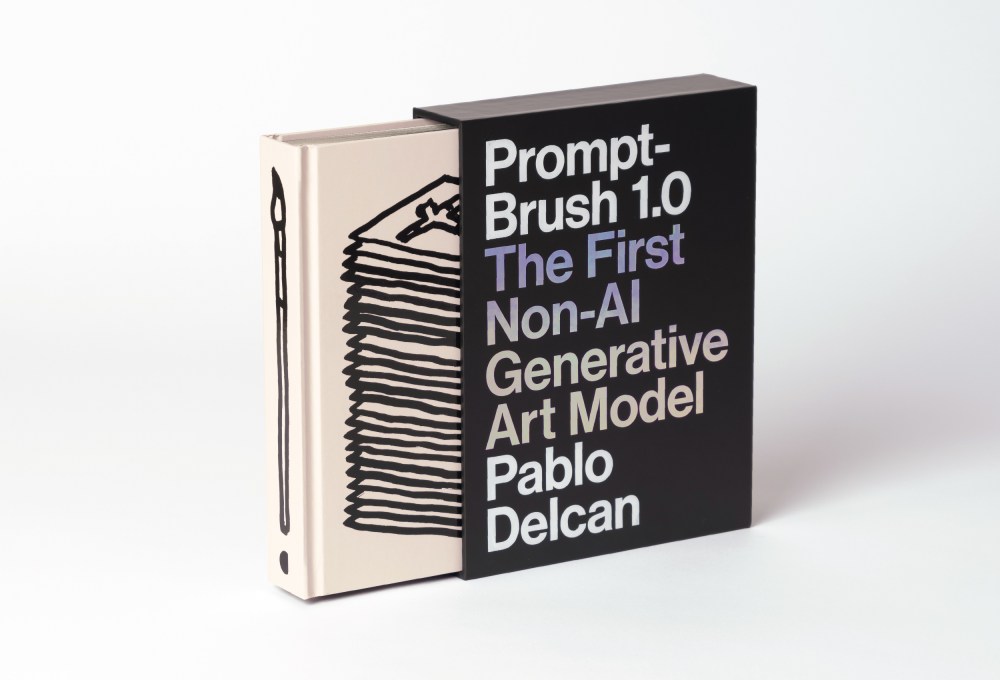

Am I right in assuming that the design of the book (e.g., cover type and slipcase) is so elegant as to underpin a message about the superficiality of AI, or am I just projecting?

I wanted the first impression of the book to feel like it could have been designed by an AI company to promote their cool new model. I wanted it to feel sleek and elegant, like a box that would contain the latest technology. And when you slip the book out of this box, a body of work that is the opposite.

What are your favorite five prompts? And why?

Four are “purpose,” “resilience,” “anxiety,” “forgiveness.” I really liked drawing these because they were hard to turn into an image. I felt that I had to dig into my own life to visualize them as opposed to finding more generic or universal ways of drawing them. I feel like everyone would have a different way to interpret these words, or a different experience that comes to mind when they imagine these words as an image. It was also interesting that I received these prompts repeatedly from different people over the past two years. My fifth favorite prompt is “chair,” mainly because I like to draw them.

Is there a sequel in the works?

The book ends with me having a conversation with a chatbot I created that I named Echo. I asked Echo about a sequel and for some ideas on how to continue this project. Echo made a pretty good case for ending the project at 1.0 but it also invited me to let the next phase of the project surprise me. I don’t have anything currently planned or in the works for 2.0. Right now I continue to draw prompts and am trying to catch up with the demand.

Are you learning to co-exist with AI? Is this your olive branch to a fearsome technology, or a declaration of war?

I love this question. I think coexisting with AI might entail being at war with it at the same time. I don’t think we should let AI dictate our future and I’m really interested in this tension between the two. I’m excited by AI, I feel empowered by it but I also think it’s important to understand it and its potential if you want to be able to push back against it.

How should this “handbook” be used by artists or wannabe artists?

I think this was my way of trying to find my voice through this very simple exercise and experiment. I’d love for people to think of this moment as cathartic, a moment to reinvent ourselves and our industry and shake off some of the dust, and rediscover our purpose and why our contributions are not only important but also irreplaceable. I would love for people to experience this book and come up with their own way to respond to this moment.

What do you want readers to take away?

I want readers to feel empowered. While there is so much anxiety and doom around AI, there is an opportunity for real human work to flourish.

The post The Daily Heller: On Becoming a Robot Impersonator appeared first on PRINT Magazine.