As a kid, I had an ant farm that I stared at for hours at a time. I like looking at bugs, but I don’t like touching or being touched by them, which is why I prefer my insects to be in display cases. This is where Peter Kuper and I part company. He’s an artist-entomologist, and I would never have guessed that fact until I saw his 2022 INterSECTS exhibit at the New York Public Library, exploring the 400-million-year history of these creatures and the remarkable entomologists who have studied them.

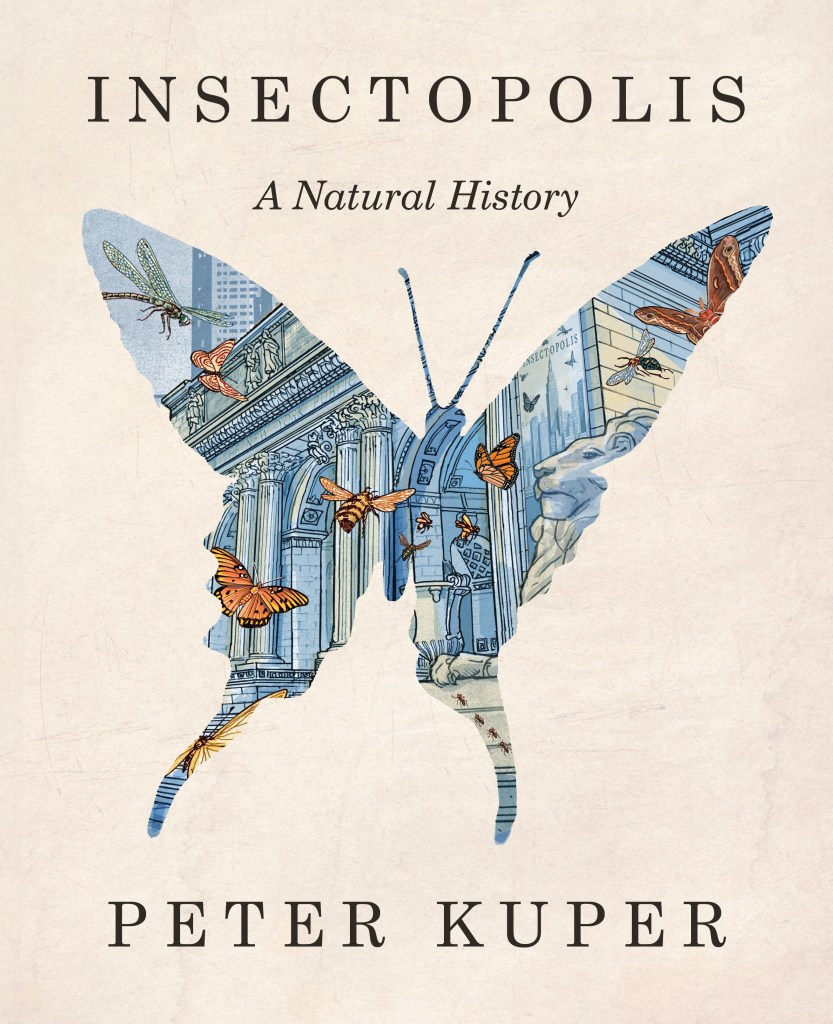

Moreover, in his recent book Insectopolis: A Natural History, he’s combined history, science and design while illuminating the work of pioneering naturalists like E. O. Wilson and Rachel Carson. It’s arguably his most beautiful work, and was funded, in part, by the NYPL’s Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center Fellowship.

Kuper’s intricate drawings include swarms of insects—bees, ants, cicadas, butterflies, silkworms, beetles, dragonflies and more—flying, crawling and interacting with the various rooms of the library. On the occasion of Insectopolis‘ publication today, I asked Kuper to enlighten me on why he’s become such a big bug fan.

(The images below are from the chapter on cicadas, the sex and sleep-loving, noise-making variety of insect.)

How many species of insects do you cover?

The entomology world believes there are something like five-and-a-half million species—and have only described about a million.

One of the new bees recently discovered by expert Michael Engel, he was kind enough to name after me (scaptotrigona kuperi).

But to answer your question, I have no idea.

Where does the word bug derive from?

It seems to have originated from the Middle English word “bugge,” from about 1620, meaning “something frightening” or “scarecrow,” specifically related to bedbugs.

Bug as it’s used to connote computer problems goes back to Edison and a cockroach, but was apparently codified in 1947 when an actual moth gummed up a computer panel.

Why are some insects more appealing than others?

Color would be a big reason—butterflies are mind-blowingly exquisite to look at; also, they don’t sting. Stinging weirdly puts some people off—go figure.

I’m at a point where they are all beautiful to me in some way. One of my goals with Insectopolis is to make people who outright hate them to reconsider.

If you like, say, chocolate, coffee, fruits, honey, the shine on apples and M&M’s, etc., you should at least appreciate insects. The second biggest pollinator after bees? Flies.

Has this long-term investigation changed your attitude toward insects in all aspects of your life—intellectual and spiritual?

Learning that our society would collapse without insects (I’m not just saying that—this is a fact) has made me look at every one of them with a new regard.

I am mesmerized by them, and that opens up my consciousness to all the amazing tiny giants that are fluttering about.

Not to overstate it—I’ll still swat a mosquito that’s biting my arm, but as a rule now I avoid ending any of their lives.

Excerpted from Insectopolis: A Natural History. Copyright ©2025 by Peter Kuper. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

The post The Daily Heller: Peter Kuper Takes a Bug’s-Eye View of the World appeared first on PRINT Magazine.