Fourteen years ago, thereabout, I wrote this missive in support of Ralph Steadman:

Dear Honorable Sirs,

I write this letter urging you to consider bestowing knighthood on Ralph Steadman, caricaturist, illustrator, artist, writer and satirist of considerable renown.

Mr. Steadman is one of the few extraordinary visual satirists of the late 20th century who, through his adult and children’s books and editorial drawings, has captured the zeitgeist and critiqued with great acuity the social, political and cultural scenes. It is safe to say he is the Hogarth, Gilray and Rowlandson of his—our—time.

I have known, worked and written about Mr. Steadman for decades. He is a chapter in two of my books—Man Bites Man and The Savage Mirror. I have employed him as a master satirist at The New York Times. I have written critically and glowingly about his various books, notably those on Leonardo Da Vinci and Sigmund Freud, which shed comic light on their lives and work through the lens of honest biography and history.

England claims many great wits as its own. Mr. Steadman stands out for his artistry, intelligence, insight and, more than anything else, his longevity as a distinctly uncompromising voice.

I look forward to learning that he can be called Sir Ralph.

Very Sincerely,

Steven Heller

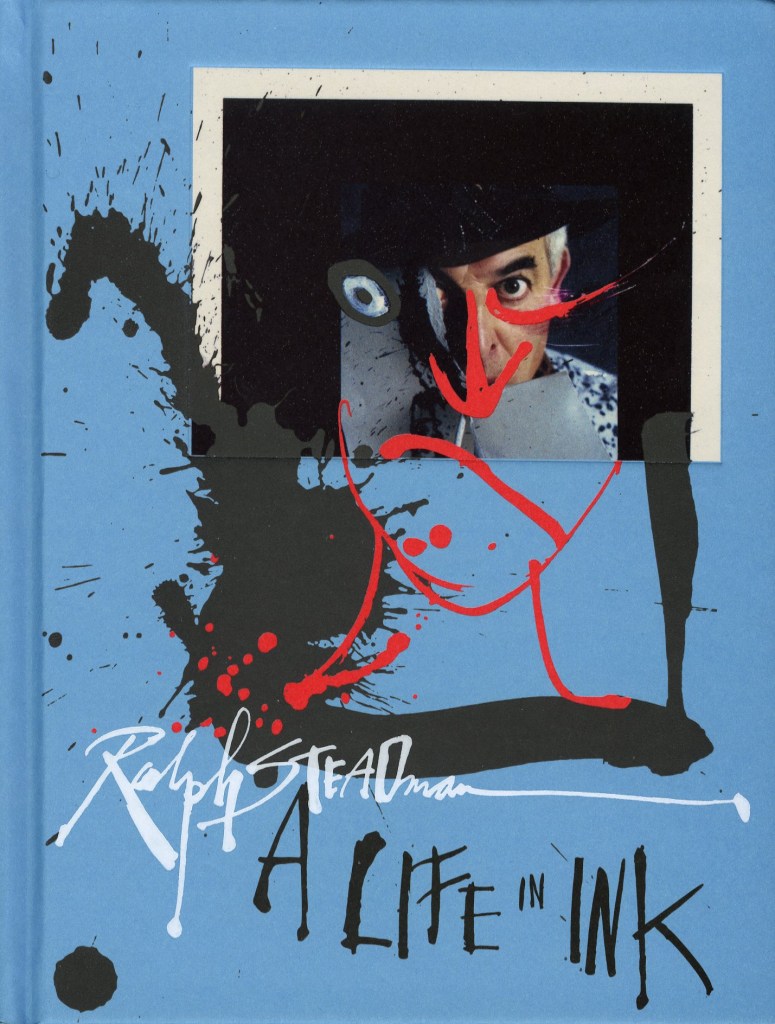

To my knowledge, there is still no “Sir” at the beginning of Ralph Steadman’s name. Maybe because it is that the make up of his rogues’ gallery observes no favor but is filled by his past and present legacy of playing Whack-a-Mole with the heads and other body parts of his favorite betes noir, U.K. politicians and royals, U.S. presidents Nixon, Ford, Reagan, the Bushes and Trump (he may have done Clinton, Obama and Biden too, but I haven’t seen them). He admits his antipathy to leaders in his monograph, A Life In Ink (Chronicle Chroma), of which a new mini edition has just been released. “Everyday I draw,” he says in the book’s brief interview. “I never know where it will take me. … I feel it’s my duty to Confront the Menace—whether that be your local constable or the President of the United States. People can make change happen, and the governments can be made to do the right thing—if we step up and demand it.”

Not all his work is retribution for the ill-makers of the world. Steadman has illustrated his share of classics, Alice in Wonderland, for one; Animal Farm, for another; and classic historical figures in the arts. His work generally feels angry and cutting, in part owing to the written scrawls that are stains on many drawings. And some exude the loathing contempt he has for some of his targets.

As alluded in the letter above, when I was art director of The New York Times Op-Ed page, I inherited Steadman from my predecessor and his predecessor before him. This was after he made a name as Hunter S. Thompson’s Gonzo partner. I would have accepted the job if only for that opportunity to work with him. I used a fair number of his drawings (often drawn five times the size of reproduction). The irony was that I gave him manuscripts to illustrate, which he often did in such a savage way that my editors wouldn’t allow them to be used with the intended article. But they were SO GOOD they could not just be killed, so we found other stories for them to illustrate.

Steadman is so masterful and eloquent with his art that keeping them off the page would have been a crime (and not even gun-shy editors could justify or condone such savagery). This edition of A Life In Ink is not a record of all his famous images—nor does it give much useful anecdotal context for their respective uses. But it contains many pictures I’ve never seen before. It’s an undeniably important record of his never-ending quest to expose the world’s abundant follies—and although he wouldn’t ever really want it, the book might just pry the coveted “Sir” out of the timid reactionary gatekeepers who continue to deny him the honor.

The post The Daily Heller: Ralph Steadman, Forever Satiric appeared first on PRINT Magazine.