President Harry S. Truman launched the nuclear age by greenlighting the Atomic blasts over Hiroshima and Nagasaki 80 years ago this week. The world has been plagued by threats of nuclear winter ever since—and it’s been a tough job keeping the genie in the bottle. Memory is our best deterrent, and this week we honor those who miraculously survived the horrors—and an artist who did his utmost to make the reality of war a concrete memory. In honor and peace, below is a Daily Heller reprise from Sept. 24, 2020, featuring the first anti-nuclear protest artist to put pen into ink in the war against war.

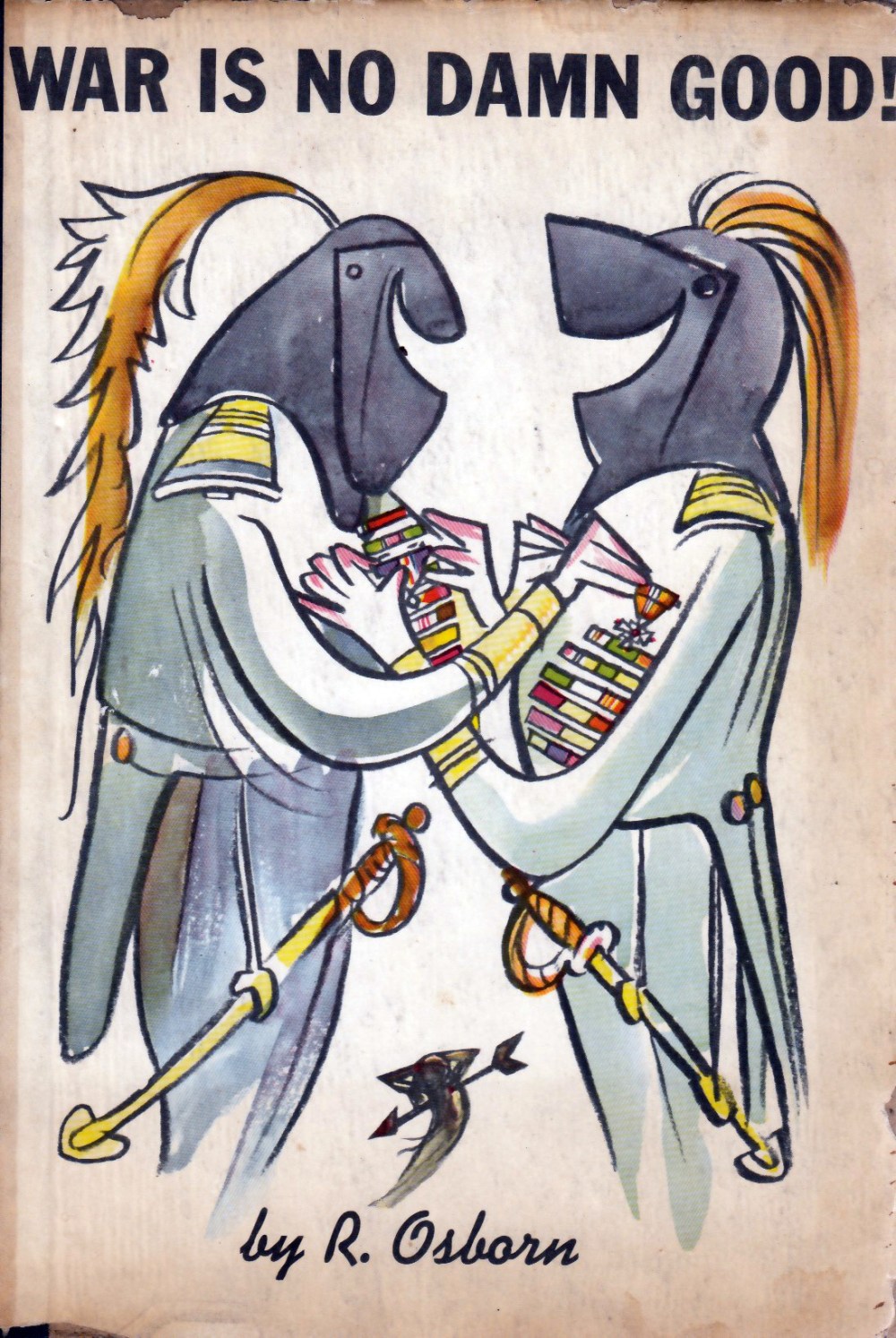

A few months after the end of World War II, former U.S. Navy Lieutenant Robert Osborn, an expressive and satiric artist whose assignment was drawing witty cartoons for training and safety books and brochures, published a cautionary manual of a different kind. Rather than teach sailors and pilots survival techniques under battle conditions, his book War is No Damn Good sought to metaphorically save lives by condemning all armed conflict, and especially the nuclear kind.

While serving his country in the South Pacific, Osborn had seen many horrors and supported the ends. But after viewing photographs from Hiroshima and its atomic aftermath, he realized the means were not beyond reproach and as an artist he could not squelch his indignation. Thus emerged the first protest icon of the nuclear age. His drawing of a smirking skull imposed on a mushroom cloud transformed this atomic marvel into a symbol of death. Although it was a simple graphic statement, it was the most poignant of the precious few anti-nuclear images produced after World War II.

This was the most startling, but only one of countless icons, images and graphic commentaries that Osborn created over his lifetime. He was an artist of conscience, man of conviction, and antecedent of the great cartoonists and commentators who attacked injustice and lampooned folly. He was the American Daumier. He reported on the comedie humaine and was critical of affairs of state that were not very comic. His expressive pen and brush line was known to anyone who read The New Republic, Life Magazine and The New York Times, or his satiric books On Leisure and Paranoia, and the autobiographical Osborn on Osborn. His work defined the social satiric milieu of his era because he stripped bare the pretense of hypocrites and fools, of which there where many.

The post The Daily Heller: Robert Osborn on the Crime of War appeared first on PRINT Magazine.