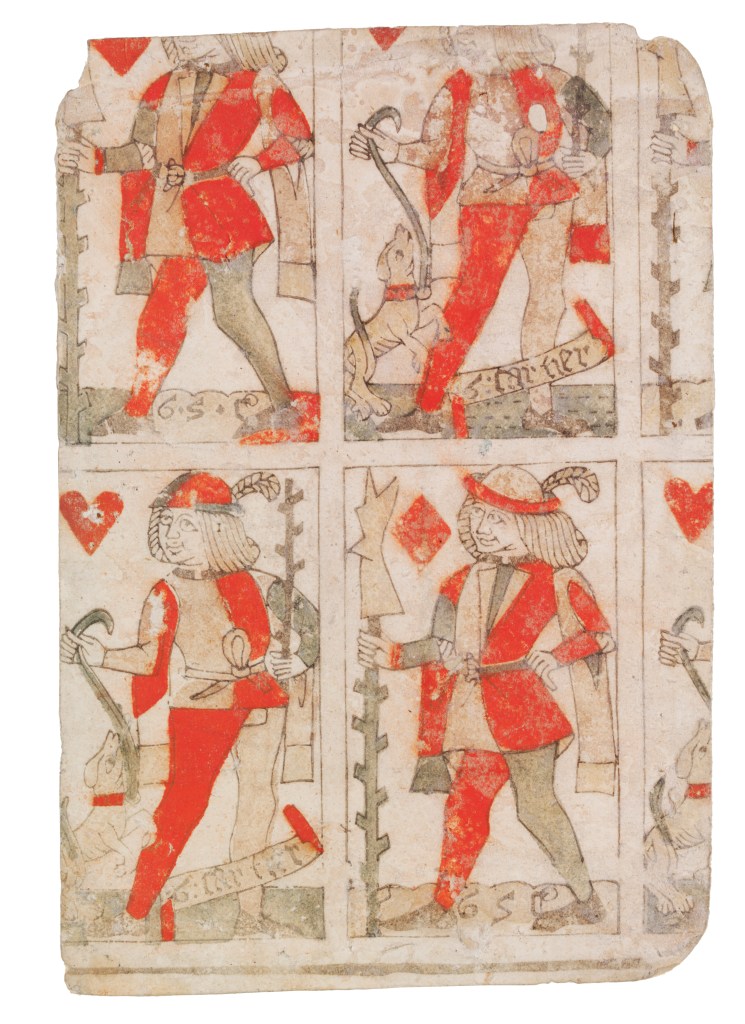

GSC (probably Gilles Savouré), part of an uncut sheet of playing cards, late 15th century, woodcut on paper with stenciled coloring. ©V&A

For the first few years of my collecting life, I specialized in inexpensive screenprints of the kind that were sold at galleries specializing in the WPA. They included gritty scenes by anonymous printers and illustrators whose names are unknown today. Most of the collection has been given away, but I’ve always been drawn to silkscreen, pochoir and stencil limited editions. There is a kind of group intimacy to art that is made in multiples but pulled by a human hand. I always wanted a book that traced the lineage of these printing methods—and now there is a good one, Screenprints: A History by Gill Saunders (Thames & Hudson), published in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Saunders, a V&A researcher, begins this unique narrative of screenprinting by examining its early artistic precursors, including the stencil and pochoir printing of Henri Matisse’s Jazz and other artists’ books. Starting in the 1960s, screenprinting became one of the most important techniques in the rise of limited-edition fine-art prints, and this volume showcases works by notable artists from this key period, including Roy Lichtenstein, Eduardo Paolozzi and Andy Warhol.

The book also celebrates the medium’s important role in protest movements as an inexpensive and rapid method to create colorful and impactful posters, among them the Atelier Populaire pieces made during the workers and student revolt of 1968 Paris.

I asked Saunders to give us a docent’s tour of her book, which uses most of the examples from the vast V&A collection.

Artist unknown, The Happy Marriage, designed c. 1700, published c. 1754-64, woodcut with stencil coloring on paper. ©V&A

You write that the initial popularity of screenprinting occurred in the 1930s. Why did it take so long?

I wouldn’t say that it took a long time for screenprinting to become popular as a fine art medium. The process of silkscreen printing (developed out of stencil printing) was trialed for commercial purposes in the 1870s in France and Germany, but patents for the process were only granted in 1907 (UK) and 1915 (USA). Initially it was used only by commercial printers for producing banners, posters and retail display material. It was only when certain American artists had gained experience of working with screenprinting in commercial print shops that they began to experiment with it for making their own limited-edition art prints in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Only at this point did it come to be recognized as a cheap, accessible and viable means of making affordable art for the mass market.

Was the increase in creating and making prints a desire to make art more affordable to the masses? I recall the AAA gallery in NYC sold Rockwell Kent’s print work for as low as $5 to political organizations.

Yes, the rise of screenprinting was closely tied to a desire on the part of artists, and later publishers and galleries, to make fine art accessible and affordable to a wider market. For example, in 1940 the Museum of Modern Art in New York held an exhibition titled Color Prints Under Ten Dollars; this featured 70 works, the majority of which were screenprints. Although screenprinting became increasingly sophisticated, the basic means and materials were always cheap and easy to work with, allowing artists to produce their own original prints. Later, many artists chose to partner with skilled printers such as Chris Prater, who founded the legendary Kelpra Studio in the UK in 1957, specializing in screenprinting. Some of the more complex and ambitious prints produced at Kelpra and other professional studios were expensive, but by comparison with etchings and lithographs, screenprints have generally continued to be more affordable.

Wallpaper or lining paper with formalized floral design imitating contemporary embroidery or lacework; anonymous: English; late 17th century; print from woodblock. ©V&A

The cover of the book features Robert Indiana’s very famous LOVE image. Would you say that this poster is the “poster child” of the entire discipline?

Robert Indiana’s LOVE is an iconic image, which he produced in various media, including painting and even sculpture. It was published as a limited-edition screenprint (and was reissued in variant colorways) before it was reproduced as a poster, and it embodies all the qualities we most associate with screenprints—bold, bright, evenly printed colors and hard-edged shapes. It is one of the defining motifs of Pop Art, and Pop Art is closely associated with screenprinting because all the major Pop names—Warhol, Lichtenstein, Wesselman in the USA; Richard Hamilton, Joe Tilson, R.B. Kitaj and Eduardo Paolozzi in the UK—made screenprints, often referencing the commercial origins of screenprinting in their own work.

Robert Indiana, Love. Courtesy Thames & Hudson. ©Thames & Hudson / V&A

So much of the 20th century Pop art screenprint work derives from commercial arts. Is this why I see so much typography, advertising and politically focused work in the volume?

For many of us, I think, screenprinting is indelibly associated with the 1960s, and in particular with Pop art and Op art, and with hard-edged abstraction. This period is often taken to be the high point in screenprint’s relatively short history, and it was undoubtedly an important moment in confirming screenprint as a major fine art medium. Pop art also drew on screenprint’s commercial origins, and the pristine clarity of graphics and advertising, but at the same time Pop could be “political,” sometimes explicitly so, as in much of Warhol’s work and Richard Hamilton’s, or implicitly, as in the work of Sister Mary Corita Kent. But in a sense, Pop art, in all its rich complexity, has never really gone away—it has continued to be a powerful influence on many artists since then, ranging from Christopher Wool and Damien Hirst to Ciara Phillips, Scott Myles and many of the so-called “Street Artists,” from Miss Tic to Ben Eine. And like any other medium, screenprinting is constantly being refreshed and advanced by the invention and ambition of artists as they exploit new materials and techniques.

Since screenprints are so clearly identified with political action, how did they become such a monetized medium?

The screenprint has often been deployed as a means of political activism and protest, largely because screenprinted posters could be easily produced in large batches, and the basic process was so simple anyone could learn how to do it quite quickly. For the students in Paris in May 1968, it enabled them to craft immediate responses to swiftly changing events. Others have used screenprinted posters for feminist causes, for civil rights, and for anti-war protests.

However, these political applications of screenprinting have occurred in parallel with the production of much more sophisticated, labor-intensive and consequently expensive fine art screenprints. Unlike the political and protest posters, which had clear simple imagery and text printed from only one or two screens, these fine-art screenprints usually required multiple screens (each with a stencil for a different area of the design)—sometimes as many as 50 or more. For example, works by R.B. Kitaj, Jasper Johns and the photo-realist Richard Estes were all printed from many screens. These were printed on good quality art-grade papers, whereas the protest posters, which would have been considered ephemeral and disposable at the time, were printed on thin cheap paper. Ironically, these cheap “throwaway” posters (such as the Atelier Populaire examples, which were pasted directly onto walls and hoardings in the street) are now highly collectable and sought after, simply because so few have survived, in comparison with the fine-art limited-edition prints which have been carefully kept in frames or portfolios. Screenprint is the ultimate high/low art form.

Henri Matisse, Lagoon (Le Lagon), plate XVIII, from Jazz, 1947, pochoir print. ©V&A

So much of the 20th century Pop art screenprint work derives from commercial arts. Is this why I see so much typography, advertising and politically focused work in the volume?

For many of us, I think, screenprinting is indelibly associated with the 1960s, and in particular with Pop art and Op art, and with hard-edged abstraction. This period is often taken to be the high point in screenprint’s relatively short history, and it was undoubtedly an important moment in confirming screenprint as a major fine art medium. Pop art also drew on screenprint’s commercial origins, and the pristine clarity of graphics and advertising, but at the same time Pop could be ‘political’, sometimes explicitly so, as in much of Warhol’s work and Richard Hamilton’s, or implicitly, as in the work of Sister Mary Corita Kent. But in a sense, Pop art, in all its rich complexity, has never really gone away – it has continued to be a powerful influence on many artists since then, ranging from Christopher Wool and Damien Hirst to Ciara Phillips, Scott Myles and many of the so-called ‘Street Artists’, from Miss Tic to Ben Eine. And like any other medium, screenprinting is constantly being refreshed and advanced by the invention and ambition of artists as they exploit new materials and techniques.

Thomas Todd Blaylock, Dahlias, c. 1910-20, stencil print on black satin. ©V&A

What will be the screenprint’s fate in the digital world?

I think screenprinting will survive and thrive in the digital age. After all, woodcuts didn’t disappear when etching was invented, and these earlier processes were not supplanted by screenprinting, despite it being cheaper and easier to work with. All these pre-digital print processes are still used by artists, and they choose to work with whichever method gives them the effects that they are aiming for. Go to any art school and you will find students making screenprints, go to any art fair and you will find galleries selling screenprints. Worldwide, print studios specialising in screenprinting are thriving and successful. People still value, respect and enjoy the handmade, perhaps even more so now when digital imagery, on screen or output to paper, is so ubiquitous and often so bland.

The post The Daily Heller: Screenprinting Makes Its Marks appeared first on PRINT Magazine.