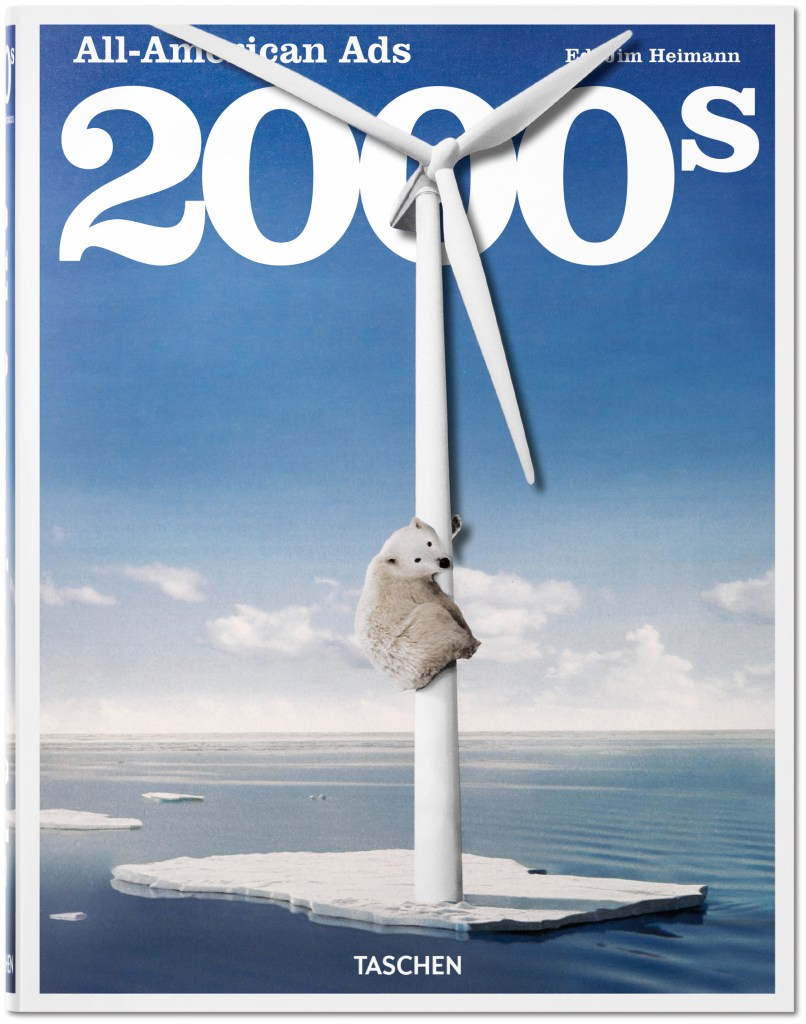

Taschen’s All-American Ads series, edited by Jim Heimann (with introductory essays by me in six of the decade-organized volumes), tells a distinct history of the United States from various vantage points.

Consumption is the most overt. What Americans have been inspired and seduced to desire, no less require, over time has changed radically, and advertisements show an evolution of everything from fashion to food, from liquor to tobacco, from lifestyle to life’s necessities, technology and beyond. The current (and probably final) book in the series that starts with 1900-1920 ends on a note of cautious optimism. The targets of American advertising have demographically shifted from clear-cut segments of the population to a melting pot in which high end and low end often meet in the middle. However, in addition to the marketplace, the media-scape—where print ads dominated creative accomplishment for almost a century—has lost its hegemony to non-print platforms, which has altered the creative focus and goals of advertisements.

There will always be a need for advertising as the spark that ignites the engine of mass consumption. But in the second quarter of the AGI-driven 21st century, the methods—and by extension, the means of reaching the consumer—have already made the Creative Revolution of the ’50s and ’60s seem quaint.

An excerpt of my 2000s introduction appears below.

Advertising did not change when the Times Square ball fell at the stroke of midnight on Jan. 1, 2000, but the industry began its creative decline in the early 2000s. Here are several indicators to support this claim: For one, the traditional print outlets for advertisements, notably magazines and newspapers, sharply declined in numbers (some turning to digital-only) during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Major advertisers were cutting print budgets and earmarking creative talent for television work. TV had already plucked away many of the most imaginative ad-people during the preceding decades, and print slipped lower down on the hierarchical ladder. Furthermore, some of the best campaigns produced and published during the early 2000s were originally conceived (and became iconic) during the preceding decade.

Yet every doomsayer pronouncement is riddled with exceptions—and mine is no exception: One of the best-known and memorable forward-facing campaigns of the millennial decade was the ubiquitous 2001 campaign for the iPod, featuring startling posters, print ads and television commercials showing black silhouettes of dancers and musicians in frozen motion, wearing white earbuds and set against fluorescent flat-color backgrounds. This work left almost all other advertising of the era, regardless of the product, in the dust. It also sold lots of iPods, which became a household fixture.

Although it is premature to pass wholesale judgement on the advertising industry during the first decade of the 21st century, it is an incontrovertible fact that what was produced, much of it fine, nevertheless fell far short of igniting a brand-new Creative Revolution, or resuscitating the old one. Other than TWBAChiatDay’s Apple ads, there were no Doyle Dane Bernbach–style Big Ideas that stand up to intense scrutiny (well, my own scrutiny, at least). Despite the creative consistency of work coming from certain key agencies—notably Weiden and Kennedy—there were inexorable reasons for a creative devolution.

The aughts were a roller coaster fraught with social, political and cultural disruptions. 9/11 certainly unhinged the American sense of exceptionalism and security. The boom and bust economy (recalling the tech bubble bursting in 2000), triggered by a flux in the technology, communication and transportation industries, as well as the failure of many startups to actually start up and succeed, had grave consequences on advertising. These, coupled with shifts in food and fuel consumption and energy sustainability, impacted environmental factors, causing marketplace volatility. A slew of demographic shifts further altered consumer loyalties and contributed to the ad-verse results during this period, which reduced the incentive of advertisers to take chances on untried ideas.

One might argue that the first decade of the 2000s was a last gasp before traditional advertising across all media transformed into something “other.” It was just prior to what would become the first juggernaut of social media and artificial intelligence, which has forever changed advertising’s form, content, distribution and reception (influencers, anyone?).

Some of America’s most popular legacy products succumbed to the pressures of fickle tastes and habits. Producers and corporations were forced to refocus on unexplored new markets to survive among new and distinctive competitive brands. In the process, the American advertising paradigm was threatened by (mostly) young upstarts that developed clever tactics for spreading “brand awareness” throughout the culture, and overtly and covertly into the hearts and minds of brand-conscious consumers (which was similar to the existential reevaluations advertising had to reconcile and reinvent to cope with the age of TV in the 1950s).

In the Digital Age, terminology began to change: “Strategic branding,” “brand story”—in short, branding this and that enveloped the distinct yet symbiotic fields of corporate identity and product-focused campaigns. Graphic design was becoming a larger factor in what the “agency of the future” promised the client. The work of 1960s and 1970s “mad men” smothered conventional establishment agencies at Art Directors Club award competitions, spawning the innovative Big Idea creative dynamic where exceptional art directors and copywriters made witty, ironic and suggestive slogans and visuals. But, by the early 2000s, these teams started to cede their dominance with, among the other social factors, the death of many national print magazines and the failure of television networks to retain large audiences in the face of cable.

This also happened thanks to the precipitous upward rise of the internet’s role in commerce and consumption. The early part of the new millennium was not, however, a total washout for advertising. This book is evidence that brand recognition and the embrace of new products flourished if the fundamental brand was seared into the consumer’s brain. Also, a bevy of futurist products and high-tech gadgets—from smartphones, pads and pods to music and video streaming services, and other lifestyle accessories—were among the mass-ticket items. Moreover, high-end status merch was ripe for “fresh creative” advertising, the most memorable being Apple products that sent droves of consumer lemmings to purchase these compact big-bang wonders. There were many other digital product ads but none that found the secret to capture consciousness.

The post The Daily Heller: The Beginning of the End of Print Advertising? appeared first on PRINT Magazine.