Fearsome images are not always depictions of subhuman or monstrous beings. The most terrifying image of the mid- to late-20th century was not a monster but a cloud. Spectators described the first atomic bomb blast on July 16, 1945, as “unprecedented,” “terrifying,” “magnificent,” “brutal,” “beautiful” and “stupendous.” Yet such ordinary words failed to convey the spectacle because, as Thomas F. Farrell, an official of the Los Alamos Laboratory, explained to the press following the first atomic test, “It is that beauty the great poets dream about but describe most poorly and inadequately.” And what the awestruck scientists and military personnel in attendance had witnessed was an unparalleled event: a thermal flash of blinding light visible for more than 250 miles from ground zero, a blast wave of bone-melting heat, and the formation of a huge ball of swirling flame and mushrooming smoke climbing toward the heavens.

The world had known staggering volcanic eruptions and devastating man-made explosions, and often throughout history similar menacing shapes had risen into the sky from cataclysms below. But this mushroom cloud was a demonic plume that immediately became civilization’s most foul and terrifying visual symbol—the logo of annihilation, the icon of the nuclear age.

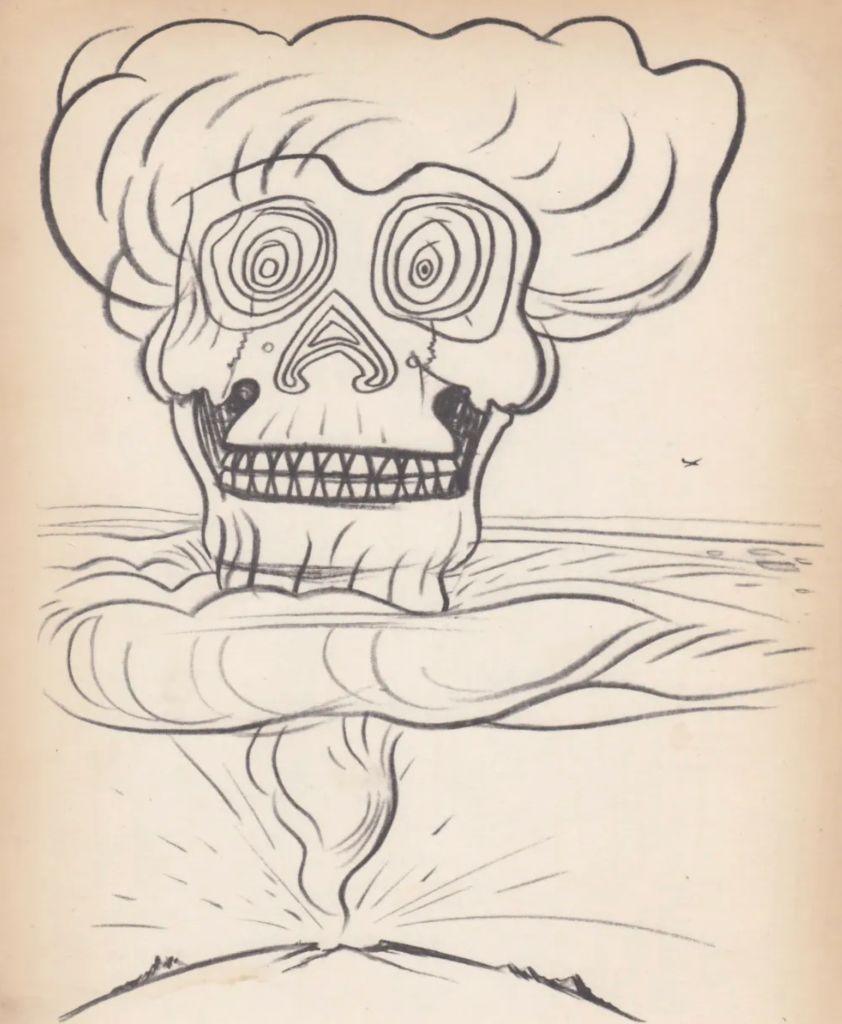

The mushroom cloud became nightmarish and ubiquitous, especially for young children growing up during the late 1940s through the late 1950s, the relentless testing period of the nuclear age when the United States and the Soviet Union executed the arms race over and below deserted atolls and underground caverns. The bomb is a modern emblem. But the mushroom cloud represented superhuman force. It symbolized righteousness rather than wickedness. Not everyone, however, embraced this view. Only a few months after the end of World War II, former U.S. Navy Lt. Robert Osborn, an artist whose wartime assignment was drawing cartoons for training and safety brochures, published a cautionary manual of a different kind. This time, rather than teach sailors and pilots survival techniques under battle conditions, his book titled War is No Damn Good condemned man’s passion for it. Osborn created the first protest image of the nuclear age—a drawing of a smirking skull on a mushroom cloud, which transformed this atomic marvel into momento mori.

But even Osborn’s satirical, apocalyptic vision pales before actual photographs and films of A-bomb and H-bomb blasts that were made of the many tests over land and under sea. Still, early into the atomic age, the mushroom cloud devolved into kitsch. By 1947, there were 45 businesses listed in the Manhattan phone book that used the word “atomic” in their name, and none had anything to do with making bombs.

French bathing suit designer Louis Reard took the name “bikini” from the Marshall Islands, where two U.S. atom bombs were tested in 1946, because he thought the name signified the explosive effect that the radical two-piece suit would have on men. Comic book publishers made hay out of mushroom mania. Atomic blasts, like auto accidents, caught the eye of many comic readers and horror aficionados. The sheer enormity of these fictional blasts, especially when seen on Earth from space, raised the level of terror many notches. Similarly, B movies in the nuke genre, with all those empty cities made barren by radioactive poison, exploited the “what-if” voyeurism that people still find so appealing. Books and magazine stories covered a wide nuclear swath. Novels such as Fail Safe and On the Beach (both made into films) speculated on the aftermath of nuclear attack and thus triggered fear (though perhaps secretly promoted disarmament, too). But to sell these books, illustrations of mushroom clouds were used in ridiculous ways. One cover for On the Beach, for example, is absurdly prosaic, showing a woman standing on a seaside cliff directly facing a mushroom cloud while waiting for her lover to return from his submarine voyage to no-man’s-land.

In 1995, the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, the U.S. Postal Service planned to issue a postage stamp showing the Hiroshima atomic mushroom cloud with the caption: “Atomic bombs hasten war’s end, August 1945.” The Japanese government protested, and the stamp was canceled. For the mushroom cloud to be so commemorated would have been an affront to the memory of those thousands killed and injured, but it would also have served to legitimize this endgame trademark rather than underscore the role of the mushroom cloud as the world’s most wicked icon.

It is no less frightening today than it was decades ago. Even though the specter of World War III as portrayed in late-20th-century pop culture has become as kitschy as those old duck-and-cover-drill training films, the cloud itself remains an indelible sign of terror.

The post The Daily Heller: The Cloud That Kills appeared first on PRINT Magazine.