A native of Texas, Eric Madsen began his design career in Houston before moving to Minneapolis. Following two early partnerships there—Frink, Casey & Madsen, and Madsen & Kuester—he founded The Office of Eric Madsen.

Madsen premiered his new book of drawings, Carlyle’s Tools, at the College of Visual Arts Gallery in Minneapolis, and it has since been recognized by the Minneapolis Foundation, the Francis Hardy Center for the Arts, the Goldstein Museum of Design, the Washington Pavilion for the Arts and the Miller Art Museum.

Here we discuss why these hyper-realistic drawings and watercolors were so emotionally intense for him, and the reason he crafted such a high-quality book.

Who was Carlyle and why does his tool collection get such grand attention?

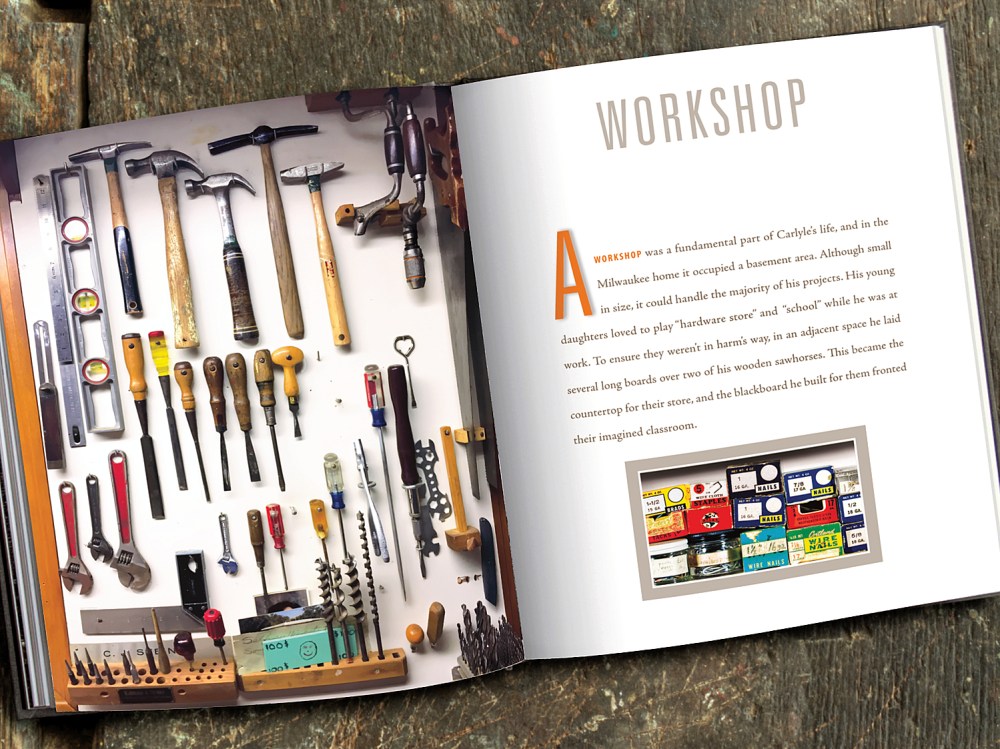

Carlyle was my father-in-law. He defined the term “tool guy.” His family heritage included furniture and cabinet makers, carpenters, plumbers and even blacksmiths. Tools were a part of his life from childhood. His career was in mechanical engineering, but when he was home, he was always in his extensive workshop. He even built his family’s personal residence in the 1930s and later a small retirement home. I spent a lot of time in his shop watching him work. A few years after he died, it was the connection I had with him and the history of these tools that became the motivating factor for me.

I knew these tools would ultimately be dispersed and gone over time. Maybe by drawing them I could somehow preserve them, while also reconnecting me with serious drawing again.

What made you decide to pursue the project in book form?

The original graphite and watercolor series actually preceded the book project by almost 10 years. After I completed the series there was an initial gallery opening followed by additional shows over the next few years. What I realized at the time was that the art and the giclée prints I was selling could not by themselves convey or preserve the story of how the process all began, the full scope of the series or my own drawing story. I knew a book would be the best way to achieve this at some point. It just took me a while to find dedicated time to tackle it.

Why else do these tools—beautiful as they appear—hold such a fascination for you?

Quite simply, their storied history. Particularly the old hand tools. If they were songs, their lyrics would move me. Carlyle, of course, had an immense collection of tools of all sizes and function. This included all the powered stuff: band saws, jigsaws, table saws, planers, drill presses and jointers. And the inventory of hand tools alone would still have me drawing today had I elected to continue. They resonated with me. They had passed through so many hands. His own, of course, and in many cases, even his father’s. His grandfather made one, the amazingly simple molding plane. His daughters had grown up with them and used them, too. When they were young, they often played “hardware store” on a little tabletop he set up for them in his workshop. The tools then passed into the hands of his sons-in-law, including me, and then on to his grandchildren. This awareness never left me when I held them

Each of your drawings is so finely and precisely detailed, but I would not categorize them as realism. Would you?

No. I never thought about them in terms of any style, actually. When I was young and began drawing, I found myself instinctively trying to capture all the details. Not sure I can explain why I was wired this way. Maybe all the Sherlock Holmes stories I loved: “You see, Watson, but you don’t observe.”

I found myself naturally picking up where I left off when I began this tool series so many years later. But it was now the “story” I was intent on capturing. This was a revelation for me, and seemed to define the difference between my childhood efforts and my approach now. Every mark or damage spot added to the story as I looked at them. Of course, no one would know if I left out a scratch, a dent or a scar. But I would. And I felt they represent the legacy of the tool’s life.

Many people have asked me how some mark happened to a tool. Honest answer? I don’t know. With Carlyle gone before I started, I couldn’t ask him, not even for all the questions I generated while drawing them. And I never thought to ask him while he was alive. For example, why is the happy birthday message inscribed on the Roofing and Crate Hatchet handle?

I spent only one-third of the time drawing. The other two-thirds were spent observing. What was the light actually telling me?

An example: The wood chisel with the black electrician’s tape on the handle. That set of old chisels had leather caps on the handle top to protect it from hammer blows. At some point it came off while Carlyle’s youngest daughter was using it. She elected to wrap the cap in electrical tape rather than glue it. The tape has a stretchy quality to it. I spent hours studying that tape before even attempting to capture the obvious stretch it exhibits.

There is an image of four paint scrapers. They are such common objects but you’ve given a kind of voice that transcends their function. Was this your modus operandi, to resuscitate them in the mind’s eye?

Honestly, I think my real modus operandi was simply not to screw them up! They each took so long to do. And I couldn’t paint over them or erase anything once the watercolor was on. But in an attempt to answer your question, I felt powerless to approach them in any other way than the way I did. As I worked on them, I did begin to picture them in my own mind as icons: a simple tool worthy of my utmost respect for the years of faithful service given. So my modus operandi, I think, was to draw exactly what was there because the details told the story of all those years. This may sound funny, but this line from the classic Paul Simon song, “The Boxer,” often popped into my head: “And he carries the reminders, of every glove that laid him down, or cut him till he cried out.”

I get an indescribable sensation looking at the Roofing and Crate Hatchet. What are the emotions these tools trigger for you?

They trigger a ton of emotions for me. The first is simply the fact I knew Carlyle for a long time. And I know the emotions he himself would have felt seeing this entire project. The fact his tools, so engrained in his life essentially as dependable utilitarian objects, had suddenly taken on such stature would have moved him. His daughters knew him best, and they agree.

There are also the emotions I have surrounding the fact he never saw the original art; was never celebrated at the gallery shows; never saw this book or was able to sign copies with me; and, he never had the chance to share his stories about them. It is a constant reminder every time I look at them. And then there are the strong emotions surrounding the actual process of bringing them to life with art. I can relate very well to your “indescribable sensation” comment. I remember one in particular.

I was working on the small whisk broom, a tool I set aside for last because it intimidated me with its complexity. At one point, as I was adding the watercolor to the graphite drawing and addressing each individual piece of straw, a drop of water hit the sheet. Instinctively and frantically, I grabbed a spare piece paper to cover my artwork and looked up to see if a ceiling pipe was leaking in my studio. There were no pipes above me. The drop of water had simply rolled out of my eye. Seeing this extremely intricate tool come to life in front of me hit me viscerally. I definitely needed a moment after that.

You state that this is nearing the end of your design career, and now you have time to focus on drawing. Why is you career phasing out?

It was an intentional phase out. For several reasons. With over five decades in the professional design field, I realized if I was ever going to begin working on my growing list of personal projects, I needed to start soon. This book was on that list. And I won’t deny that age played a role in this decision, too. The lease on my downtown office space was also expiring, and it would have required another five-year commitment on my part. This was a significant factor in my decision.

Now that the book is done. Is the connection to Carlyle’s Tools a closed chapter, or does it continue?

It is a closed chapter at this point as far as additional tool drawing goes. I feel the pressure to move on now to other projects on my list. But it continues as I deal with the books I printed, so this “chapter” in a way is not closed. I’m not sure I’ll ever really let go of it because of the connections. I will also continue designing, which I love, and art and drawing will be a part of these personal projects.

The post The Daily Heller: The Legacy of a Tool Guy appeared first on PRINT Magazine.