This is the story of a novel that is graphic but is not a graphic novel. Physically, The Absence is a brick of a book that has yet to be published as a book. It is the latest “viz-lit” created and produced by Rian Hughes, a U.K. graphic designer, illustrator, writer, typographer and sometime comic book artist who has worked extensively for the British and American publishing, music, advertising and comic book industries. He has written and drawn comics like 2000AD and Batman: Black and White, and designed logos for James Bond, the X-Men, Superman, Hed Kandi and The Avengers, collected in the Eisner-nominated book Logo a Gogo. He has published two novels, XX (Picador, Overlook Press, 2020) and The Black Locomotive (Picador, 2021). Last year he published a 600-page book collecting hundreds of typefaces that he’s designed as Device Fonts. Owing to the inherent complexity of employing about every production method in his toolbox, The Absence, his third flirtation with a text-driven manuscript, has yet to be accepted by a publisher with the finances and commitment required to publish it in Hughes’ ideal form.

Ever resourceful, he has produced a limited run of the bound book with all its typographic and pictorial specs in place. Recently, we spoke about his motivation behind creating an object with so many working parts … and how he expects to publish the same.

What inspired you to write novels?

I think I can trace the idea back to my formative years drawing comics. The kinds of graphic design and comics that appealed to me most were those that pushed the form for effect: page layout, pacing, use of close-ups, long shots, repeated frames, typographic sound effects. I realized that there was a much broader visual and textual language out there that the standard novel or comic wasn’t exploring.

The tools designers and authors now have at their disposal mean that every aspect of a book can be controlled—a novel no longer has to be set entirely in Times New Roman, justified. These constraints were a byproduct of the typesetting technology of the time, and nowadays are more of a convention than a necessity. And being a type designer meant I didn’t just have to use existing fonts—I had access to a deeper, subatomic level of graphic design I could manipulate for effect.

So I had this exciting toolbox, and I’d been frustrated that the comic scripts I was getting assigned to draw for the most part didn’t delve into these opportunities at all. That was one of the reasons I fell out of love with drawing comics—I needed to work from a script over which I had a high degree of authorial control.

This all percolated away in the back of my brain for a few decades while commercial work came to the fore, but eventually I thought I’d have to write this thing, whatever it was going to be, myself. If I wanted to design the kind of narrative experience I had in mind, no one else was going to write it for me.

The result was XX, published in 2020, which incorporated type experiments, Wikipedia articles, email exchanges, tweets, Futurist and Dada–inspired layouts, found images, magazine articles, and all manner of specially designed fonts to help tell the story.

This was followed by The Black Locomotive in 2022, which also incorporated design elements: cutaways, diagrams, a different font for every character, for example. Both have musical extras that exist outside of the books and can be accessed using QR codes at the relevant point.

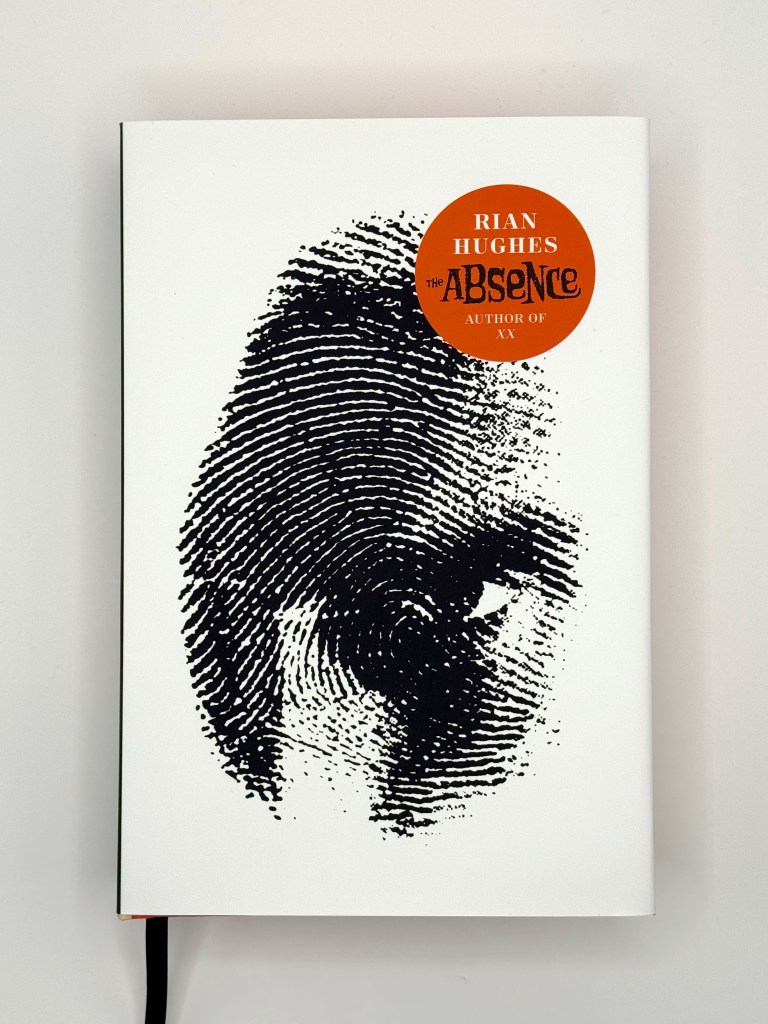

The new novel, currently unpublished, is called The Absence. I asked myself what my next logical step would be, what new, unexplored aspects of the book I could press into use. So I considered the actual form of the book itself, and what could be achieved with various print techniques. XX took the black-and-white printed page and experimented with it. Because The Absence explores the philosophical idea of the “story of story,” it addresses the physical object of the book—the “narrative container,” if you like. So I’ve incorporated color and die-cuts, and elements of the tale bleed out onto the spine, endpapers and again into musical extras that exist outside the physical object.

This unfortunately (I should have seen this coming) also proved to be expensive. My publisher, Picador, who I’m very grateful took a chance on my 1,000-page debut novel, have sadly told me it’s beyond their means.

I now have to decide whether to remove the color and die-cuts to make it into a standard format black-and-white novel, or find a new publisher with the means and enthusiasm to publish it in its ideal form. There is another option that another publisher has proposed: We could do a limited edition at a higher price point, then a cut-down standard edition for the mass market. There are a few options, but nothing is decided at the moment. If I wrote straightforward books, this wouldn’t be an issue, of course, so I’m entirely to blame.

Would you give a brief summary of the plot?

We write stories; those stories outlast us, and, in some ways, become more real than we are.

The main through-thread is the 100-year story of a fictional British pulp and comic publisher, from its birth as a private press along the lines of the Doves Press through to a large contemporary multinational conglomerate. This gave me free rein to create the characters, the story arcs, the magazines—all the kinds of design shenanigans I enjoy so much.

The fictional hero we follow from his inception in the 1930s to his latest incarnation is called Steeplejack. In-universe, he is the most recognisable British hero of all time. He’s just one of hundreds of characters in the pulps and comics who have outlived their creators to be reinvented again and again, as the times require. Now this century-old back-catalogue has been acquired by a venture capitalist seeking to exploit it as IP, and a tame AI in the basement of the publisher’s HQ is being trained on this proprietary corpus of heroes and villains. But they find that the characters are beginning to write themselves—they seem to be showing some form of volition, affecting people in the real world, first as superhero cosplay, and then more directly.

This is revealed incrementally via the main character, Adam Sinclair, a world-weary designer who has been given the job of rebranding Steeplejack and his entourage for a modern audience. As he delves into the archive we are shown these (doubly) fictional characters’ origin stories—prose and comic strips, excerpts from film scripts, old magazine articles, etc. So on one level we have the present-day narrative, and underpinning that the uncovering of the story of the mysterious origins of this publishing company, and under that, the actual pulp and comic book stories from the archive.

Steeplejack’s arch nemesis is called The Absence. The Absence, we learn, was based on a real person, one of the two founders of the original private press. The two founders fell out over the press’ direction—one wanted to turn it into a commercial concern, the other saw it as a spiritual calling.

Adam Sinclair, being a brand designer, understands the power of an aspirational logo. He’s been designing them for decades, and considers himself to be immune to their allure. But when he tries on a Steeplejack outfit his team has designed, he feels a sense of purpose course through him—a superpower, perhaps?—and realizes that the Steeplejack “S” on his chest is more than a logo: It is a rune of power, a symbol of symbols, of which all the aspirational brand marks he has created over the years are merely pale shadows. Perhaps anyone can be Steeplejack—it’s the suit that makes the man. The narrative, the story, is bigger than any one person, and perhaps anyone can cosplay as a real hero, if only for a short while.

That’s the setup—there is a larger cast, all with their own personal narratives that they are attempting to write. The relationship between story and reality, how story can shape reality, how we can easily be seduced by a story—it’s a story about stories.

From a personal point of view, it’s also a love letter to our modern-day mythologies as typified by the Marvel and DC universes, those accretive creations that have no single author but still have an essence that can be endlessly reimagined, reinvented, reinvigorated. They’re pop-culture versions of the classical myths, which almost seem to have written themselves—universal, timeless ideas clothed in the forms of gods and humans.

I’ve roped in some of my comic pals to draw the comic book sections, which I scripted—so Sean Phillips has drawn a ’60s Steeplejack and Penny Black strip, Duncan Fegredo the Steeplejack origin story, Dave Johnson Steeplejack’s 1970s reincarnation in TV2000 (my amalgam of venerable British comics 2000AD and TV21), David Roach a swinging ’60s romance story. I drew a couple, too, revisiting my comic book roots.

What is the occult secret of your “fictional” publishing house?

The small private press on which Steeplejack’s publishing empire was built is the Malrunar Press—it was, as I say, inspired by the real-life Doves Press, founded around 1900 on the banks of the Thames near me in Hammersmith, London. There’s now a museum on the site. The press used just one size of a special typeface they’d commissioned for their exclusive use—16pt “Doves Type”—and no illustrations. The 50 or so books they printed all have this pure, austere design, and are expensive collector’s items.

The founders, Thomas James Cobden-Sanderson and Emery Walker, were temperamentally very different, and by 1909 were in a protracted and bitter dispute involving the rights to the Doves Type. As part of the partnership dissolution agreement, all rights were to pass to Walker, but to scupper this, Cobden-Sanderson threw all the matrices and punches from Hammersmith Bridge into the River Thames. This took him 170 trips, over many months.

It was considered lost until 2015, when designer Robert Green, with help from the Port of London Authority, searched the riverbed near Hammersmith Bridge and managed to recover 150 pieces of the original type, on which he based a digitization. I’ve use this for the Malrunar Press sections of the book.

In my fictionalized retelling, the remaining founder who goes on to build the company into a modern publishing juggernaut bases the character of The Absence on his puritanical rival, Carter Curwyn—my version of Cobden Sanderson. As Steeplejack’s nemesis, he wants to destroy all pictorial representation. This, I have to point out, is not a new idea—many religious and philosophical ideologies have tried to ban realistic artistic depictions. So The Absence begins as an unflattering caricature—but later, through a wartime encounter with Aleister Crowley, who is running an unorthodox section of the Secret Service during WW2, he manages to step out of fiction into the “real” world and achieve a degree of corporeality.

And, of course, the thing he wants more than anything else is to destroy the modern company that is the heir to the Malrunar Press.

So, how do you fight a fiction? With another fiction: Steeplejack.

And if you can’t do that here in the “real” world, Adam Sinclair realizes, maybe you’ve got to become fictional yourself.

This is an impressive tome on a production level. How did you plan and execute it, given the changes in paper, design and typography?

As with XX and The Back Locomotive, I wrote it directly in InDesign, which meant I could see what it looked like in the relevant font in real time—a great boon for capturing the right tone. InDesign also gives you a thumbnail overview of the whole—I could immediately see where the text and the images fell, and where the rhythm and flow might need adjusting.

To begin with, I wrote short descriptions of what each chapter should contain—the philosophical ideas, the plot points I needed to hit. This evolved—I combined some sections, opened up others, moved chunks around, deleted more. This is much easier with a visual overview. It’s similar to how I work when I’m designing a regular book. The first stage is like a sketch, a skeleton, which I then flesh out. It’s how I was taught to approach life drawing—get the main thrust, the posture down, and the rest of the piece will naturally unfold from there. Keep it flexible as long as possible and the most natural shape for the story will emerge.

How much time was devoted to producing this opus?

Around five years since finishing The Black Locomotive—though that wasn’t five solid full-time years, as I’m always working on my usual design, type and illustration commissions in tandem.

What do you want the reader to take away?

An immersive experience, an appreciation of the forms storytelling can take, both traditional and pictorial. And to be diverted, entertained, have their mind stretched in invigorating ways.

And to come back next time, for the next project …

The post The Daily Heller: The Protagonist of This Novel Wants to Destroy All Pictorial Representation appeared first on PRINT Magazine.