Photomontage has long been an effective propaganda weapon for right, left and center. The Communists used it. The Fascists used it. Virtually every party and regime, despot or democrat in the 20th century has used it to manufacture messages and memes that documentary facts could never achieve. And with Photoshop, the art and craft of photomontage continues, and so does photo manipulation—often for deceitful ends.

John Heartfield is arguably the most famous photomontagist in the design canon. He is credited with having invented “political photomontage” when he adorned the Dada newspaper Everyman His Own Football with pictorial commentaries satirizing Weimar leaders. He later produced a tantalizingly wicked series of acerbic montages for the German Communist newspaper AIZ (Workers Illustrated News), attacking the growing Nazi party, its leadership and its relations with oligarchy. His montages are today some of the most memorable political “caricatures” of the era.

But he was not alone in his resistance to Hitler. An equally prolific, though much less celebrated, “fotomonteur” was the Danish-born Marinus Jacob Kjeldgaard (1884–1964), known as Marinus, who resettled in Paris, where from 1932–1940 he attacked Fascists (Mussolini, Hitler), Communists (Stalin) and French reactionaries (Pierre Laval) in photomontage tableau, usually on the front pages of Marianne, a French leftist cultural and political newspaper.

Marianne was founded in 1932 as an antidote to what its editors chided as a preponderance of rightwing journalism throughout France. Marinus, who moved to Paris in 1906 and 10 years later made covers and other images for the French periodical J’ai Vu, was tapped to be the main visual commentator for Marianne.

The very first issue of the broadsheet included a photomontage parody of an Aesop’s fable about the hare and turtle, where the turtle, representing the goddess of justice, is beating the hare, a capitalist exploiter. Many of the earlier montages focused, like more traditional editorial cartoons, on political and economic folly. But the main target of the paper’s ire was the rise of the criminal elements in Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Marinus picked up relentless steam as 1933 rolled around, when Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor.

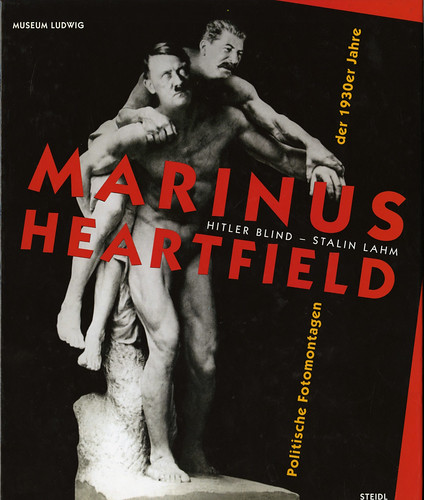

Marinus Heartfield: Politische Fotomontagen der 1930er Jahre (Steidl), edited by Gunner Byskov and Bodo von Dewitz (who also contribute essays), is a richly illustrated catalog of an eye-opening exhibition at the Museum Ludwig in Köln. This is the first time I’ve ever heard of this artist, who arguably did as much for montage-caricature as Heartfield. And while he may have been more prolific, even in France his work seemed to vanish during the Vichy and Occupied periods, and after liberation too.

While Marinus’ images evoke Heartfield, he had a distinctive personal style. The most obvious difference was format: AIZ images were vertical, Marianne’s were horizontal. Heartfield went for the grand gesture, Marinus often relied on more narrative tableau. Heartfield was fairly minimal, Marinus filled his images with melodramatic detail. Marinus also found some incredible scrap from which to work. The photos of Hitler and others looked as though they were made especially for the montages they are in.

The catalog rectifies the lack of documentation on Marinus in design, meme and cartoon histories. It is rich with beautifully printed reproductions of his numerous montages along with reproductions of Marianne pages. The historical references in text and picture also abound, placing Marinus in context. Alas, the only problem: For now the book is only available in German. My translator enjoyed reading passages to me, like a mom reading a picture book to a child, but a full reading would have been prohibitive.

The post The Daily Heller: When Photomontage Was AI (Augmented Imagery) appeared first on PRINT Magazine.