What if the buildings of tomorrow could breathe, literally? What if architecture didn’t just minimize its environmental impact but actively contributed to healing the planet? These are the provocative questions at the heart of Picoplanktonics, a groundbreaking exhibition by the Living Room Collective at the Canada Pavilion for the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025.

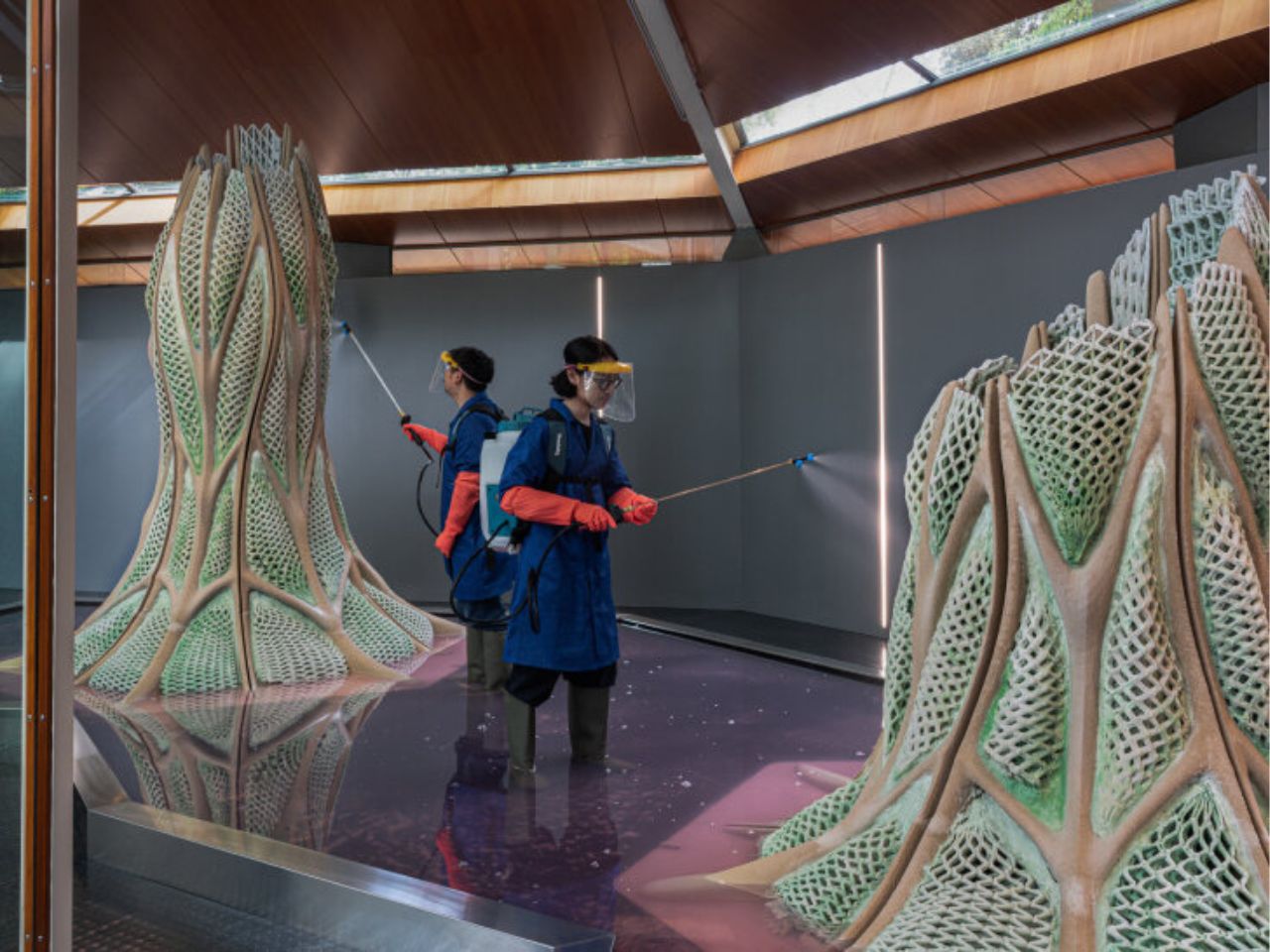

Commissioned by the Canada Council for the Arts and led by architect and biodesigner Andrea Shin Ling, Picoplanktonics is not your average design showcase. It’s a living experiment, a radical fusion of biology, technology, and architecture, where live cyanobacteria are embedded into 3D-printed biostructures that actively capture carbon dioxide from the air. Running from May 10 to November 26, 2025, this exhibition invites us to rethink what materials can do, and what design should mean in an era of ecological urgency.

Designer: The Living Room Collective

The design world is no stranger to the term “regenerative design.” It’s often used in the context of recycled materials or circular systems. But according to Andrea Shin Ling, that’s just scratching the surface. In Picoplanktonics, regeneration refers to its biological definition: the capacity to heal, to renew, to grow back stronger after decline. The materials here are not inert. They live. They breathe. And, crucially, they regenerate.

The biostructures in the pavilion don’t just sit pretty. They perform. They are infused with cyanobacteria, among the earliest photosynthetic organisms on Earth. These tiny powerhouses were responsible for the Great Oxygenation Event over 2.4 billion years ago, a planetary transformation that turned Earth’s carbon-heavy atmosphere into one rich in oxygen. Today, their ancient metabolic superpowers are being reimagined to tackle modern-day carbon emissions.

The Living Room Collective merges two core biological processes in the installation: photosynthesis and biocementation. While the former captures and transforms CO₂ into oxygen, the latter goes a step further, transforming carbon dioxide into solid minerals like carbonates. Think of it as a natural form of cement, permanently locking carbon away in hardened structures. Unlike conventional cement, which is a carbon-heavy villain of the construction industry, this process is not just carbon-neutral, it’s carbon negative.

What’s more, the cyanobacteria don’t come in after the fact. They are part of the material from the moment of printing. Fabricated at ETH Zürich, the biostructures are 3D printed with the bacteria already alive within them. This means the bacteria continue the job that human designers began, hardening and finishing the structures from the inside out, given the right environmental care.

That care is essential. The team behind Picoplanktonics treats the installation like a living organism. It needs warmth, humidity, sunlight, and saltwater to thrive. Luckily, Venice delivers all of those in spades. The city’s unique climate and the conditions of the Canada Pavilion itself became integral to the design.

Still, as with all living systems, unpredictability is part of the process. “A bioprint might dry out if the air is too dry that week, and many of the bacteria die,” explains Shin Ling. “But because the system is regenerative, the bacteria population has the potential to restore itself when favorable conditions return.” It’s a delicate, ever-changing balance, one that demands monitoring, adaptation, and even emotional investment. This is architecture as cohabitation, not just construction.

In an era where climate resilience and material innovation are no longer optional, Picoplanktonics offers more than just inspiration; it offers proof of concept. A new kind of material ecology. A building block for a post-carbon world. One that doesn’t just mimic nature, but invites it in.

Visitors to the Venice Architecture Biennale can witness the living structures evolve in real time, watching as biology and design blur into one. It’s not just an exhibition. It’s a living system, an active experiment, and perhaps a glimpse into the future of what architecture could, and should, be.

The post This ‘Living Building’ uses Bio-Cement that absorbs CO2, making the architecture carbon negative first appeared on Yanko Design.